I think, therefore I laugh: What now for Pinoy satire?

MANILA, Philippines — To say that political satire in the Philippines is a dying art form is wrong. It has simply become unpopular.

Veteran comedian Jun Urbano, who created the comic character Mr. Shooli in the 1980s for his hit show “Mongolian Barbecue,” agrees with the observation. So does former Film Academy of the Philippines deputy general Leo Martinez, who popularized the character Congressman Manhik Manaog.

Asked to weigh in on the issue, film-TV director Jose Javier Reyes said, “Satire, which is high comedy, is supposed to make people laugh, then think. Problem is, people just want to laugh and don’t think.”

Meanwhile, public anthropologist and film critic Tito Valiente agrees that political satire as an art form in the Philippines “needs saving,” and that “we can no longer use it as a weapon” these days.

For sociologist Josephine Aguilar-Placido, who’s focusing more on “that big paradigm shift” that the Filipino audience experienced recently, viewers have now “reached their saturation point” and are now “looking for new faces and flavors.”

Just silly stuff

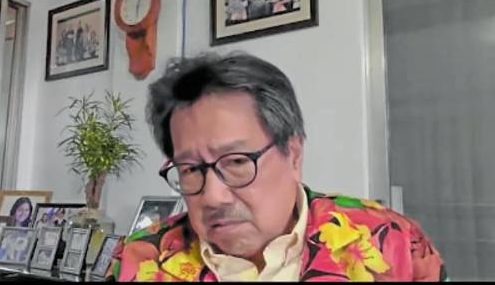

Urbano, son of the late National Artist for Film Manuel Conde, recently created a YouTube channel and has been regularly uploading vlogs featuring Mr. Shooli, the character he’s most famous for, expressing views on social issues “in a funny way.”

However, Urbano would feel disappointed whenever he’d look at the low number of views per video. “Meanwhile, vlogs that feature people doing silly things get more clicks than mine,” observed Urbano.

Mr. Shooli predates the unapologetically tactless Hollywood character Borat, made famous by Sacha Baron Cohen. Critics say Shooli’s observations parallel Borat’s confusion with the American way of life. In 1991, Urbano’s film “Juan Tamad at Mr. Shooli sa Mongolian Barbecue” was an entry to the Metro Manila Film Festival, where it won six awards.

‘Pikon’ politicians

Other examples of shows that utilized politics as a form of entertainment include “Sic O’Clock News,” (1987-1990), which featured Jaime Fabregas, Pen Medina and Ces Quesada; and “Abangan ang Susunod na Kabanata” (1991-1997), starring Nova Villa, Tessie Tomas, Noel Trinidad and Freddie Webb.

Martinez noted that the politicians who came after President Fidel V. Ramos, who served from 1992 to 1998, have already gotten too “pikon” (sensitive) to jokes directed at them.

“They took themselves too seriously. Puro balat-sibuyas (onion-skinned)! Some even urged our advertisers in secret to pull out of our shows. That actually contributed to the decline of satire,” said Martinez, who’s also a theater actor and director.

“These days, people prefer in-your-face exchanges. I’m not surprised. Having a President that curses in public encourages constituents to curse as well. Politicians brought personal expression to this level, that’s why there’s so much hatred online. People no longer want parody … ang pagtira ng padaplis. Everything’s head-on,” Martinez observed.

Valiente, meanwhile, said that while it’s not necessarily damaging, the impact of political correctness (PC) to satire has been huge. This is where “shaming” comes in. “Part of parody is you make a caricature of a person, like a politician, his habits and behavior, like his stutter or the size of his ears.”

High requirement

One known satirist and impersonator in the ’90s is Willie Nepomuceno. He was famous for poking fun at personalities who ran for president. Some referred to him as the country’s king of impressionist art for his impersonations of former Presidents Ramos, Ferdinand Marcos, Joseph Estrada and Benigno Aquino III.

“Another factor is that the audience’s sense of humor has changed through the years. Political satire requires an audience with a higher level of education for it to be truly appreciated,” pointed out Valiente, who likewise recalled the brand of comedy prevalent in the 1960s.

“In the comedies churned out by Dolphy in those days, the focus was ‘yellow’ humor, or pagtatae. After that, comedians made fun of people who were pilay (crippled) or ngongo (those with cleft lips). That faded away slowly,” Valiente recalled. “These days, you have to ask: To what degree can you make people laugh at the expense of these politicians? Because they can turn the tables around and say you’re ‘shaming’ them.

“I was part of a generation that could comment on any topic without limits. There used to be a time when we weren’t too concerned with having so many brackets. These days, there are simply too many no-nos,” he observed. “That’s contrary to the common notion that we’ve become more liberated.”

PC ‘hypocrisy’

Reyes couldn’t agree more. “This whole idea of political correctness has become a bastion of hypocrisy. Yes, there’s body shaming. Everybody has a crusade, that’s well and good. But this is humor we’re talking about. There’s a very big difference between high comedy, which is satire or intelligent humor, and humor that is merely abusive or insulting,” he began.

“If I insult somebody to make people laugh, that’s low comedy, because I am using a person’s defect to make my audience laugh. But if I make fun of this person not because of his looks alone but because of what he represents, then that’s a different matter altogether,” Reyes explained. “The beautiful thing about satire is that it’s not created merely to generate laughter. It’s supposed to make you laugh, then think. But people nowadays just want to laugh and not think.”

Reyes then pointed to the “great satires happening in other parts of the world,” such as the American sketch comedy “Saturday Night Live.” He explained: “When you laugh at what you see in the show, you know it’s an objective form of laughter…that it’s satire. Here, hit on a person lightly and he and his supporters will take it seriously. That’s crazy!”

Not dead, just different

Reyes then refused to say that satire is dying. “If you’ve seen the sentiment ads (“Pagod Len-Len”) of Sen. Imee Marcos that were written and directed by Darryl Yap, they’re satirical. But we see now that this satire serves a specific political agenda. You know that it’s being used as a campaign material. The fact that people respond to it-as well as to (actress) Angelica Panganiban’s ‘Huwag Magpabudol’ video-means that satire is still very much alive…just in a different form.”

Reyes said that sadly, satirical plays no longer have venues, “because the times are restrictive. You will no longer see Willie Nep today,” he pointed out. “These days, satire serves the purpose of propaganda, and not as objective criticism. Notice that the two strongest political camps are getting back at each other through satire.”

Reyes could be referring to presidential candidates Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. and Vice President Leni Robredo, the two personalities allegedly benefitting from the “Pagod Len-Len” and “Huwag Magpabudol” viral videos, respectively.

Placido, meanwhile, observed that “the internet resulted in one big paradigm shift in audience preference. Mas lumalim na ang mga tao. They saw that we could do more, that we could do better.”

Placido further said: “With this in mind, we now want to avoid trivial presentation of candidates. Making candidates the laughingstock is no longer part of the structure. We now have not just a thinking audience, but one with a heart-a humane audience-and they want something ‘new.’”

So what does the “new” audience expect to see? “New faces, because they offer new flavors,” Placido pointed out. “The delivery should be different as well. The youth has a language that the older ones could not deliver well. It’s more likely that older viewers are also clamoring for something new, especially since repetition is one technique in propaganda that diminishes the interest of the public.”