La Salle-DOST project seeks to preserve Mangyan script

WRITING SYSTEM | Surat Mangyan survives in the crafting of inscribed poems, but researchers are also pushing for its revival in common usage. (SCREENGRAB FROM REPORTED PRESENTATION OF DR. ROCHELLE IRENE LUCAS / Department of Science and Technology)

MANILA, Philippines — An old, disparaging myth about the Mangyan tribes in the island of Mindoro was that they had tails “half a span long.”

That was how the 17th century Italian traveler Giovanni Careri described them, according to the medical anthropologist Violeta Lopez, who wrote in a 1974 article that Careri’s impressions were based on the accounts of Jesuit priests “who probably mistook the Mangyan ‘bahag’ (loincloth) for a tail.”

That myth has long been discredited, but today’s Mangyan — mainly composed of eight tribes — increasingly face modern-day challenges in preserving their distinct culture.

One aspect of that culture is the Hanunoo, the native language from which they developed a writing system predating the Spanish era, called Surat Mangyan.

This precolonial orthography, or the representation of spoken sounds by written letters and other symbols, is also said to have evolved from India’s ancient Sanskrit.

A research team from De La Salle University is trying to preserve that legacy among the indigenous peoples (IP), with the support of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST), particularly its National Research Council of the Philippines.

In 2020, amid a nationwide lockdown prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, the team managed to develop a mobile electronic dictionary of the Hanunoo language.

The researchers also recommended the inclusion of Surat Mangyan in the curriculum for IP learners from kindergarten to Grade 3, and in the mother tongue-based multilingual education curriculum of the Department of Education’s Indigenous Education Program.

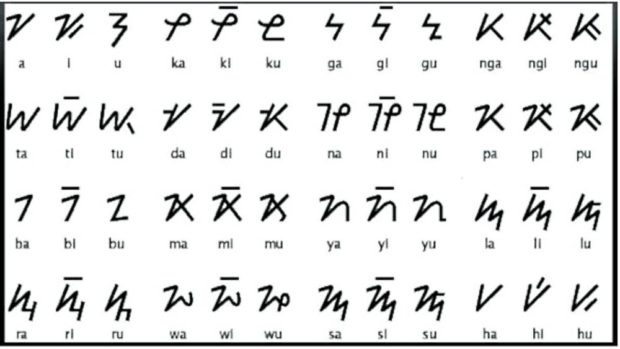

The Mangyan script is composed of 18 characters, three of which are vowels while the other 15 are written in combination with those vowels.

‘Language loss’

Dr. Rochelle Irene Lucas, who heads the team, noted that the younger Mangyan generation was no longer literate in its own writing system.

“[This] will eventually lead to [a] language loss in [terms of] writing their script,” she said.

But as a spoken language, Hanunoo remains very much alive “in social interactions at home and in the community,” the researchers said after conducting a survey among Mangyans.

Hanunoo “is also a source of identity and … of pride, which primarily is the driving force for [a] language to survive [amid] encounters with people from the dominant cultures,” they said.

Yet only a few of the 170 respondents in the survey were able to identify the Mangyan script, according to Lucas.

This made the language “critically endangered,” as her team put it, because of the limited use of its writing system.

The group recommended that the script be used in documenting gatherings, rituals and other activities among the eight tribes that make up the Mangyan population — the Alangan, Bangon, Buhid, Iraya, Ratagnon, Tadyawan, Tawbuid and Hanunoo.

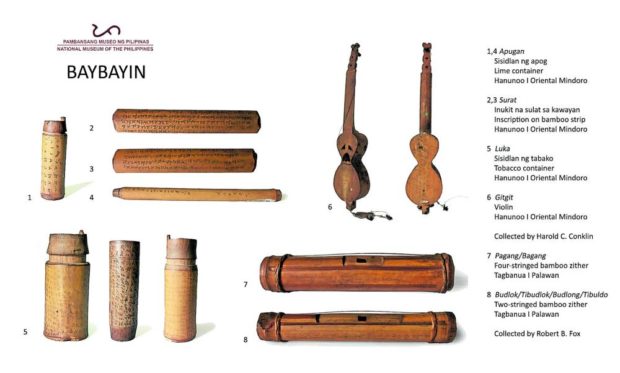

The verses of the Mangyan’s literary pieces are usually scribed on bamboo internodes and wooden objects like “apugan” (lime container), “luka” (tobacco container) or “gitgit” (violin). –PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE PHILIPPINES

Poems, songs

Despite Surat Mangyan’s lack of common usage, it stands out, remarkably, as the medium for writing traditional poems such as the “ambahan,” with its seven-syllable lines, and the “urukay,” a poem of eight-syllable lines that borrows words from the Western Visayan languages and even Spanish.

The National Commission for Culture and the Arts said these poems are “written by stylus or knives on slivers of bamboo.” They are also performed as songs—“sung or chanted with guitars, fiddles, flutes or Jew’s harps.”

According to the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP), the poems are also written on wooden objects such as the “luka” (tobacco container) and “apugan” (lime container), on musical instruments and even on house beams.

“The script is also used for love letters and other correspondences such as … notifications of ceremonials,” the NMP said.

Although Lucas’ team found a lack of familiarity with Surat Mangyan among the youth, the NMP said there are young people studying the poems, songs and prayers written on luka and apugan.

The late Dutch anthropologist Antoon Postma, who spent decades studying Mangyan culture since his first contact with the tribes in 1958, described them as a “very attractive people in their lack of affectation, [their] resourcefulness and apparent self-sufficiency.”

While their culture somewhat adapted to modernity, as they replaced stones with iron tools, for example, “the Mangyans continued to prefer their own traditions, which they consider the better way of life,” Postma said.

RELATED STORY

Mundong Mangyan: How Mindoro’s Alangan Mangyan face land disputes, lack of teachers, child marriages