CATARMAN, Northern Samar—Describing it as the best way for the youth to appreciate Northern Samar’s glorious past, the provincial government is putting up an exhibit on its rich history and culture.

The show aims to identify, preserve and protect artworks and artifacts in the province and to instill local pride through a chronicle of past significant events.

Perrain Rebadulla, provincial consultant for culture and the arts, said History, Culture and the Arts Exposition Center would open in Catarman, the capital town, on June 15 or four days before Northern Samar’s 47th founding anniversary. To be displayed are historical documents, paintings and photographs of old churches and cultural properties.

Battle of Catubig

Part of the province’s glorious past is what is now known as the “Battle of Catubig,” which has been described by the US War Department as “the heaviest bloody encounter yet for the American troops” against Filipino freedom fighters.

Wielding bolos, pistols, spears and Spanish Mauser rifles, about 300 militiamen, led by Domingo Rebadulla, a respected resident of Catubig, staged a surprise attack on the detachment of the US 43rd Infantry Regiment during the Philippine-American War on April 15, 1900, in Catubig town. Church bells rang to signal the start of the assault.

Although superior in firearms, the Americans retreated to their barracks.

The militiamen were later reinforced by 600 members of Gen. Vicente Lukban’s revolutionary army.

After two days of skirmishes, the guerrillas set the American barracks on fire, throwing burning abaca bales into the building.

Unable to put out the flames, the Americans were forced to flee and face their attackers. One group of 15 US soldiers made a dash to the boats in the nearby Catubig River, but all of them met their deaths. A second group dug trenches at the back of the smoldering convento and were able to hold out for two more days until reinforcements arrived.

The four-day siege left at least 150 Filipino guerrillas and 21 American soldiers dead and eight others wounded.

Catubig Mayor Fredicanda Dy said the municipal council was preparing a program to commemorate the 112th anniversary of the Battle of Catubig in April.

Sumuroy Rebellion

Another historical event to be featured in the exposition center is the Sumuroy Rebellion of 1649-1950.

On June 1, 1649, Agustin Ponce Sumuroy led an uprising against the Spaniards in Palapag town as the natives resented the polo y servicio (forced labor) system imposed by the Spanish colonial government, which required them to work in shipyards in Cavite.

The rebellion spread like wildfire to other parts of the Visayas, Bicol and even to Mindanao. It lasted for a year or until Sumuroy was finally captured and executed in June 1650.

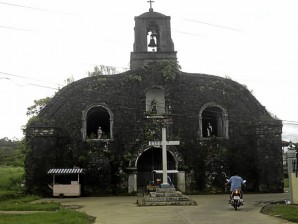

The National Historical Institute installed markers on Sumuroy’s statue on March 15, 2009, and on the church ruins of Palapag on June 1, 2008, both in Palapag, and on the Battle of Catubig site on April 15, 2007.

Das story

Perrain Rebadulla said he intended to go to the island-municipality of San Antonio, meet with relatives of Florentino Das and gather documents on his family background and incredible sea voyage.

Das stowed away from the Philippines to Hawaii in 1934 on board a US-bound British merchant ship in Manila. In Hawaii, he got married and had eight children. To feed his big family, he worked as a boxer, boat builder, fisherman and mechanic.

But he longed for his homeland and wanted to prove that Filipinos were also good sailors. So he embarked on a historic solo voyage across the Pacific Ocean, according to some accounts.

He sailed from Hawaii to the Philippines on May 15, 1955, to April 25, 1956, on board the Lady Timarau, a 24-foot boat that he built himself, leaving behind his wife and children.

Along the way, according to one account, he “encountered several typhoons, faced life-threatening situations, and had to stop and repair his boat … He refused to heed his sponsor’s call to abandon the voyage, demonstrating an unwavering will and spirit to succeed.”

Unfortunately, little is known of what happened to Das upon his return. He reportedly died on Philippine soil in 1964, but no one knows where he was buried.