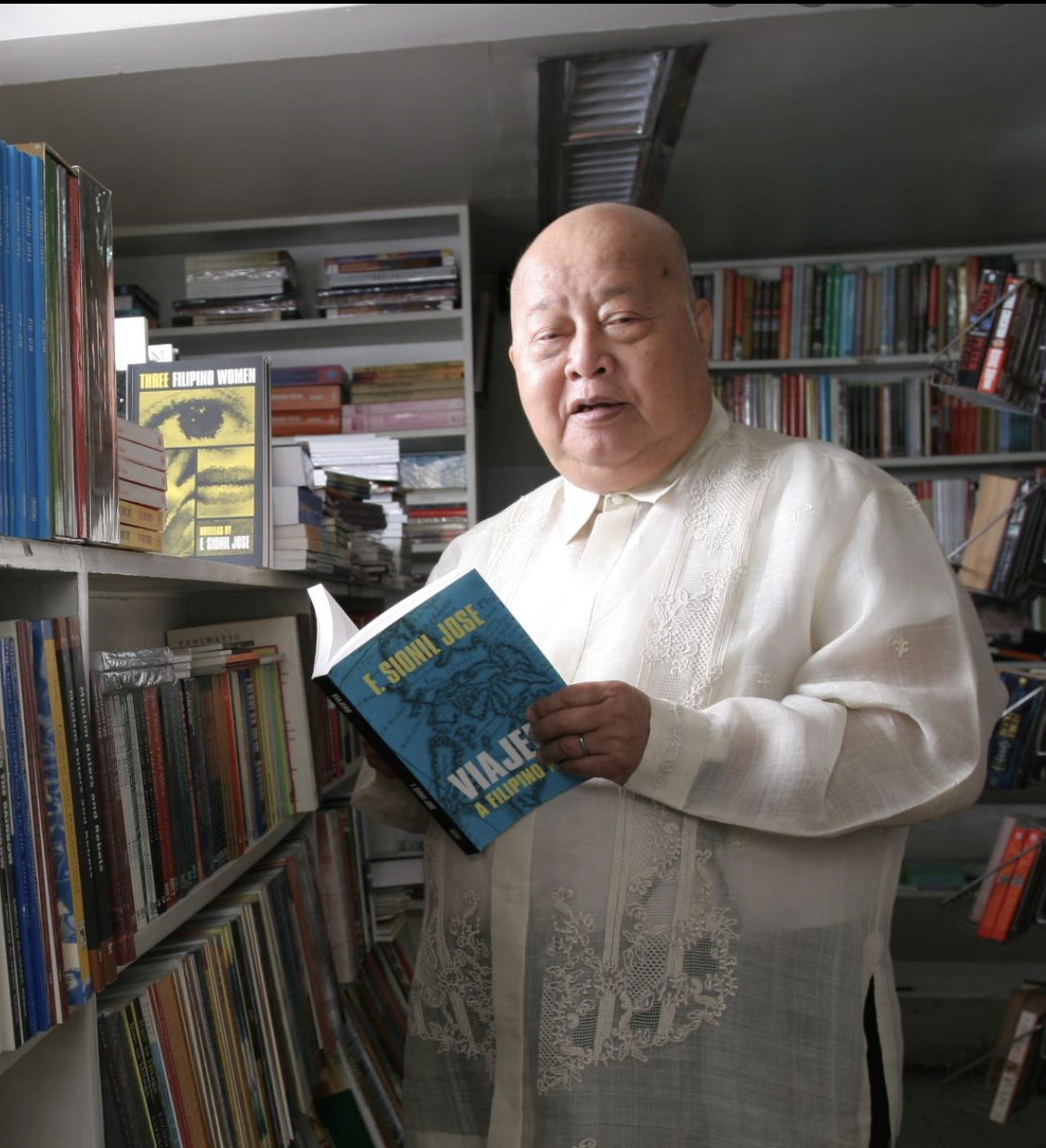

F. Sionil Jose. Image lifted from his Facebook page

National Artist for Literature F. Sionil José, one of the Philippines’ most prolific, awarded and controversial writers, died late on Jan. 6 in his sleep. He was 97.

A statement from the Philippine Center of International PEN (poets, playwrights, editors, essayists and novelists) confirmed that José died at Makati Medical Center where he had been scheduled for an angioplasty yesterday. His wife, Teresita Jovellanos José, said he was pronounced dead at 9:30 p.m.

In a 2011 interview with the Inquirer, the beret-wearing José—“Frankie” to friends—confided that he was afflicted with diabetes and a heart condition. He said he had “an intimation” about the future, and recalled his fellow National Artist for Literature Nick Joaquin, who “just went to sleep and did not wake up anymore” in 2004.

“I hope that’s what will happen to me. I am not scared of death,” he said, and credited his long life to his wife.

Malacañang on Friday paid tribute to the late national artist and sent condolences to his family for his passing.

“He is not just a legendary writer and storyteller, F. Sionil José is also a true patriotic Filipino,” acting presidential spokesperson Karlo Nograles said at a press briefing.

Nograles added: “To his wife, Ma’am Tessie, and his entire family, colleagues and loved ones, our prayers.”

Required reading

José was the author of over 30 books, and his works have been translated into over 20 languages. He wrote essays, newspaper columns and short fiction, but he is best known for his novels, some of which are required reading in literature classes.

His five-book Rosales saga, which includes “Po-on” (1984) and “Mass” (1974), discuss class struggle and revolution in the Philippines and are considered his masterpieces. His last book is the 2011 novel “The Feet of Juan Bacnang.”

He was named to the Order of the National Artist in 2001. He received the Ramon Magsaysay (RM) Award for Journalism, Literature and Creative Communication, the Carlos Palanca Memorial Award for Literature, and awards from France and Chile, among others.

Since 1965, José was the proprietor of Solidaridad Bookshop on Padre Faura Street in Ermita, Manila, considered by many as the best independent literary bookstore in the Philippines and a venue for many literary gatherings often hosted by José himself.

In 1957, he founded the local chapter of the global group PEN.

Opinions

Part of the citation for his RM Award reads: “Although it is difficult to quantify, José has probably made his greatest contribution through the guidance and assistance he has offered numerous Filipino and foreign writers, artists and scholars.”

While he was known to dispense advice and encouragement to younger writers, José was also one of the most controversial among Filipino writers for his opinions.

Most recently, he was heavily criticized for attacking the choice of Filipino journalist Maria Ressa for the Nobel Peace Prize. He also defended and supported President Duterte’s “war on drugs,” downplayed the shutdown of the media network ABS-CBN (“Its demise, I dare say, is even good for Philippine democracy if it also means the dismantling of the Lopez empire,” he said), and questioned the patriotism of the Filipino Chinese community.

And he was unapologetic for his views. Asked in the same 2011 interview if he had ever regretted the things he said, José replied: “No, never, because that’s how I feel. Why should I regret it? I don’t regret those things because we should have a strong critical tradition—which we don’t have. If I don’t like what my friends are doing, I tell them to their faces. And they are welcome to tell me the same thing! If I can dish it, I should be able to take it, too—which I do! And I don’t get mad at these people who tell me, ‘You’re a lousy writer.’ I don’t care.”

He was born Francisco Sionil José on Dec. 3, 1924, in Rosales, Pangasinan province.

An impoverished childhood was softened somewhat by his mother Sofia, who encouraged his love for literature. She led him to read José Rizal’s “Noli Me Tangere” and Victor Hugo’s “Les Miserables,” books which kick-started an admitted obsession with social justice in his works.

After World War II, José matriculated at the University of Santo Tomas, where he wrote for the campus publication, The Varsitarian. He eventually dropped out of school to pursue writing professionally as a journalist and went on to win awards for his fiction.

He wrote in a small office two floors above his bookshop, where a lifesized bust of himself, beret and all, by the sculptor Julie Lluch can also be found.

A devout Catholic, he attended Mass daily.

‘Mayabang’

Throughout the years of writing, winning awards and running his bookshop, José also voiced his opinions in print and speeches and, eventually, on Facebook.

“All writers are mayabang [conceited] and I am no exception. You will not be a writer if you are not mayabang. All of us are deeply conceited,” he declared in 2011. “Yung yabang na iyan, we express it in different ways. Some have it under control; some have it in the way they act, they speak, even in the way they write. Some mayabang writers cannot write about anything except themselves.”

He believed that the role of the writer was to maintain a country’s collective memory: “To help make this country, to shape this country, into a nation—and you can only do that if people have memory. It’s sad, because they don’t. Edsa 1 lasted only one generation. We’ve forgotten.”

José’s remains were cremated on Friday and his ashes will stay in the family home for the meantime. Teresita said she was awaiting the arrival from abroad of four of their five children and would announce the funeral arrangements shortly.

The National Commission for Culture and the Arts also said state ceremonies for the national artist would be announced in time. —With a report from Leila B. Salaverria