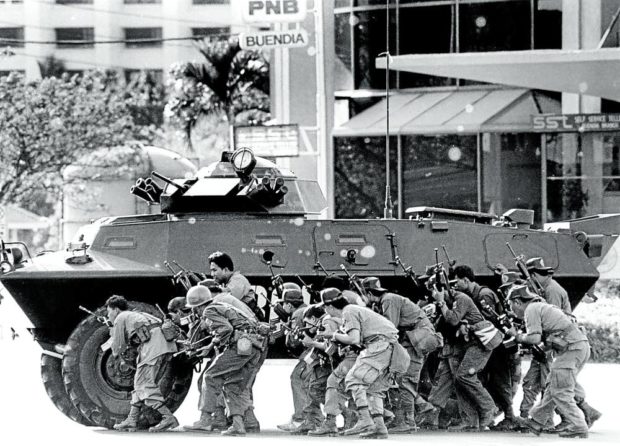

5TH AND DEADLIEST: The Makati City central business district turned into a battlefield in what was considered the most serious challenge to the Cory Aquino administration. The December 1989 coup attempt lasted for nine days. (Photo by ERNIE U. SARMIENTO / Philippine Daily Inquirer)

LOS ANGELES — The name Danilo Atienza may not ring a bell to Filipino millennials. But a quick Google search of him may make them realize that if not for his heroism 32 years ago, they may not have the precious freedoms they enjoy today.

Some in the Philippines may not even remember that on Dec. 1, 1989, brave Filipinos like Atienza played a key role in defeating a violent and bloody military coup d’etat that almost toppled then President Corazon Aquino from power.

As a 38-year-old fighter pilot of the Philippine Air Force, then Lieutenant Atienza was killed in the bombing raid aboard the F-5 jet he was piloting, but he destroyed several rebel aircraft at Sangley Point in Cavite province, breaking the back of the mutiny of more than 3,000 rebel soldiers that relied heavily on air power.

A Batangueño who once dreamed of becoming a wealthy businessman, Atienza instead earned the eternal gratitude of a nation as Sangley Point — the military base that he defended with his life — is now named after him.

I still recall with dread that first Friday of December 1989 how the country could have ended in a fratricidal civil war as tanks rolled down the streets of Manila, a trio of “Tora-Tora” airplanes, and a black Sikorsky helicopter hovering menacingly under clear skies.

After bombing Malacañang and burning Camp Aguinaldo, the rebels — led by a cabal of right-wing soldiers and loyalists of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos (who died on Sept. 28 that year) — came close to taking power. And then the Americans came, snatching defeat from the jaws of the rebels’ victory.

Bush’s order, Powell’s role

“BUSH SAVES AQUINO,” shouted this newspaper’s front page on Dec. 2, 1989.

While it was US President George H.W. Bush who gave the authority to help President Aquino’s request to put down the most violent and costliest mutiny against her government, it will be revealed later that it was Gen. Colin Powell, then the new chair of the Joints Chiefs, who designed the “persuasion flights” with Navy Adm. Huntington Hardisty, the plan to be known as “Operation Classic Resolve.”

The plan involved the deployment of American F-4 Phantom jets to deter rebel aircraft from taking off from Sangley Point and Villamor Air Base, and flying around Manila to scare rebel forces on the ground.

GRATITUDE President Cory Aquino at the wake of Air Force pilot Lt. Danilo Atienza in Batangas City. Atienza was killed in the bombing raid on Sangley Point that helped crush the anti-Aquino mutiny. —ROGER CARPIO

“I concocted a phrase to include in the order to convey a desired sense of menace. Our aircraft were to demonstrate ‘extreme hostile intent,’” Powell, who died last Oct. 18 of COVID-19 at age 84, wrote in his 1995 memoirs titled “My American Journey.”

“Those two US Phantom jets from Clark Air Base that roared across Manila showed everybody whose side the Americans were on,” wrote former Sen. Juan Ponce Enrile in his memoirs published in 2012.

“Sino ang traydor? Ako o ang tumatawag sa Kano para upakan ang Pilipino (Who is the traitor? Me or the one who called on the Americans to pounce on the Filipino)?” a visibly indignant Cagayan Gov. Rodolfo Aguinaldo told this writer in March 1990 as he fled from government forces for his involvement in the 1989 coup.

Aguinaldo’s Hotel Delfino mutiny in March 1990 killed Armed Forces of the Philippines spokesperson Brig. Gen. Oscar Florendo. Aguinaldo — who later became a Cagayan congressman—was assassinated on June 12, 2001, in Tuguegarao.

Davide Commission

But the Davide Commission — created by President Aquino in 1990 to investigate the coup attempts on her government—largely discounted the role of the Americans after it found out that Lieutenant Atienza had already destroyed the rebels’ air power by 12:45 in the afternoon of Dec. 1, making the “persuasion flights” of the Americans at 2 p.m. that day “questionable,” as described by the commission’s report.

“It brings home the lesson that there is no substitute for self-reliance and the removal of all vestiges of overdependence on a foreign patron,” the Davide Commission said, seemingly scolding the Aquino government in its final report.

Unmasked by the commission as one of the civilians behind the coup, Enrile went to jail (for seven days) in 1990 for his role in that uprising that killed 153 Filipinos and wounded 500 more, and cost the economy an estimated $1.5 billion.

REBEL GOV The author in March 1990 interviews then Cagayan Gov. Rodolfo Aguinaldo (right), who fled from government forces for his role in the December 1989 coup attempt. Aguinaldo was assassinated in 2001. —Roger Margallo

The 97-year-old Enrile is now supporting Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. to be the next president, prompting many to speculate if he had left the fold of the Marcoses at all.

Rehabilitated

As a 26-year-old reporter for this paper in 1990, I sat through hours of sessions at the Development Bank of the Philippines building in Makati City as the commission—chaired by then Comelec Chair Hilario Davide Jr.—also uncovered the role of former first lady Imelda Marcos in that coup, through her surrogates Serapia Cobarrubias and Luis Tabuena.

Despite the treachery of that attempted power grab, the leaders of that coup were rehabilitated: Imelda Marcos was allowed to return to the country; then Col. Gregorio Honasan II became a senator of the republic and is the current secretary of information and communications technology under President Duterte; while Gen. Edgardo Abenina, who was jailed for his role, was feted as a model citizen in 2015 in his native Quezon province, after an unsuccessful run as a senator.

The rise of Marcos Jr. in early polling ahead of next year’s elections raises the specter that his victory might again threaten civilian rule over the military—the bedrock principle of democracy destroyed by his father during his 20-year misrule as a dictator.

When that happens, it will take more brave Filipinos like Lieutenant Atienza to defeat traitorous, self-styled messiahs who again threaten the Filipinos’ dream of becoming a better democratic nation.