The Chinese dad making medicine to treat his dying son

The photo taken on October 21, 2021 shows Xu Wei holding his son Xu Haoyang, diagnosed with Menkes syndrome, after extracting urine from his bladder for testing at a hospital, at their home in Kunming in southwestern China’s Yunnan province. AFP

Blocked by Covid

Xu now gives Haoyang a daily dose of homemade medicine, which gives the child some of the copper his body is missing. The amateur chemist claims that a few of the blood tests returned to normal two weeks after beginning the treatment. The toddler can’t talk, but he gives a smile of recognition when his father runs a gentle hand over his head. His wife, who didn’t want to give her name, cares for their five-year-old daughter in another part of the city. Menkes Syndrome is more prevalent in boys than girls, and it is estimated one in 100,000 babies are born with the disease globally according to organisation Rare Diseases. There is little information or data available but Xu said pharmaceutical companies have shown little interest as the treatment “does not have commercial value and its user group is small.” Under normal circumstances, he would have travelled abroad to bring back treatments for Haoyang from specialist centres overseas, but China has largely closed its borders since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic. Xu felt he had no choice but to make it himself. “At first, I thought it was a joke,” said Haoyang’s grandfather Xu Jianhong. “(I thought) it was an impossible mission for him.” But six weeks after throwing himself into the project, Xu produced his first vial of copper histidine. To test it he first experimented with rabbits and then injected the treatment into his own body.

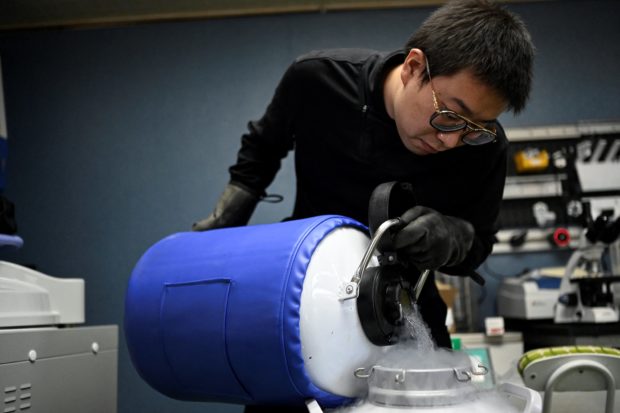

The photo taken on October 20, 2021 shows Xu Wei pouring liquid nitrogen at his home laboratory in Kunming in southwestern China’s Yunnan province. AFP

Gene therapy

His work has led to interest from VectorBuilder, an international biotech company, which is now launching gene therapy research with Xu into Menkes syndrome, along with another Chinese group called Lantu. The company’s chief scientist Bruce Lahn described it as “a rare disease among rare diseases” and said they were inspired after learning about Xu’s family. Clinical trials and tests on animals could happen in the next few months. Xu has even been contacted by other parents whose children have been diagnosed with Menkes, asking him to make treatment for their relatives too — something he has refused. “I can only be responsible for my child,” he told AFP, while health authorities have said they will not intervene as long as he only makes the treatment for home use. Huang Yu of the Medical Genetics Department at Peking University told AFP that as a doctor he was “ashamed” to hear of Xu’s case. He said he hoped that “as a developing country, we can improve our medical system to better help such families.” With a full-time role as an amateur chemist, Xu has little income and relies mainly on his parents. Friends tried to talk him out of his medical efforts but undeterred, the young father is planning to study molecular biology at university and do everything he can to protect his son. “I don’t want him to wait desperately for death. Even if we fail, I want my son to have hope.”

READ NEXT

EDITORS' PICK