STOCK PHOTO

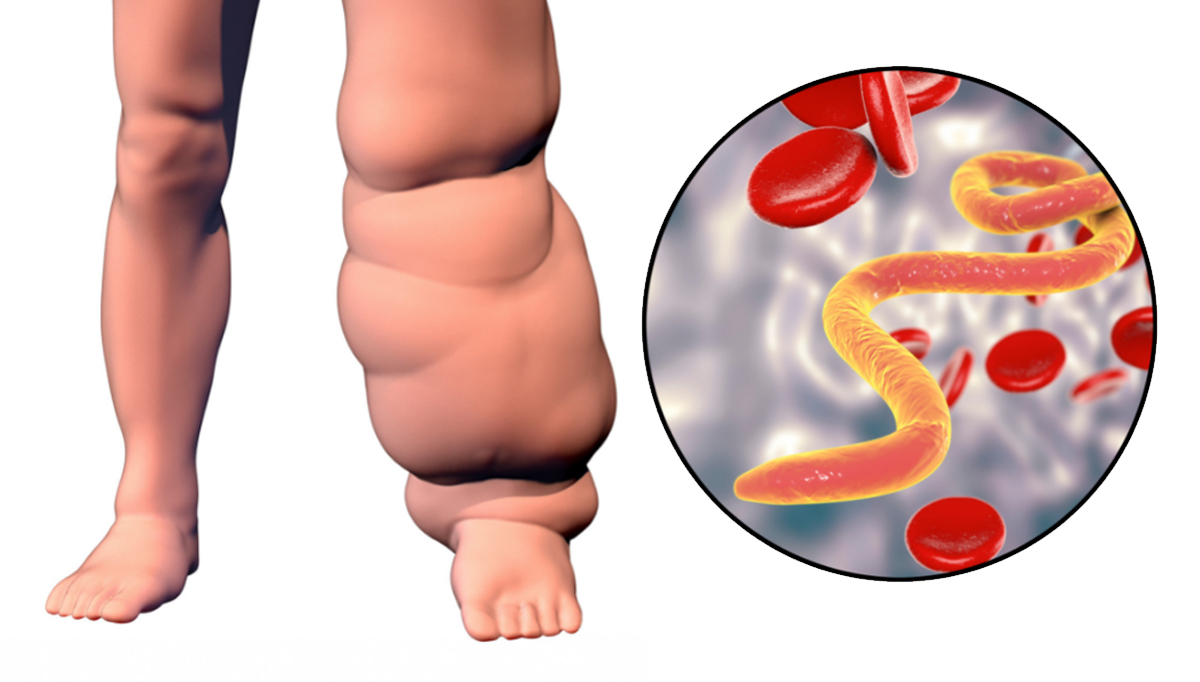

MANILA, Philippines—Aside from malaria, another mosquito-borne disease gets highlighted in the Philippines every November—lymphatic filariasis, also known as elephantiasis, a “painful and profoundly disfiguring” disease caused by mosquito-transmitted parasites.

READ: Malaria awareness month: Numbers show sharp decline in PH cases

November is Filariasis Awareness Month in the country. Although lymphatic filariasis is classified as a neglected tropical disease (NTD) —a diverse group of diseases that prevail in tropical and sub-tropical conditions—filariasis was declared as endemic in over 40 provinces in the Philippines last 2012.

In observance of the Filariasis Awareness Month, here are available data and details about the lesser-known parasitic disease in the country.

What is filariasis?

Lymphatic filariasis, as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), is caused by an infection by filarial parasites transmitted from person to person through mosquito bites.

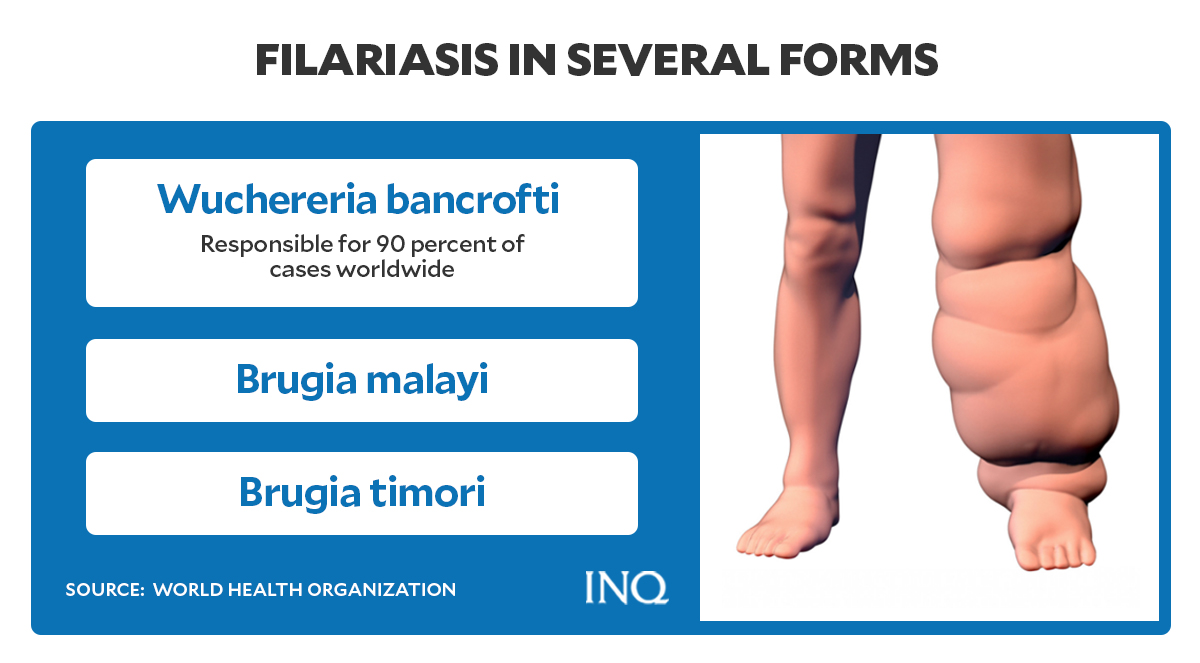

There are three types of “thread-like” worms which could cause lymphatic filariasis and are transmitted by mosquitoes. These are:

- Wuchereria bancrofti – responsible for 90 percent of cases worldwide

- Brugia malayi – causes most of the remainder of the cases

- Brugia timori – also causes the disease

Graphic by Ed Lustan

The disease is spread mainly by mosquitoes.

When a mosquito bites a person with lymphatic filariasis, microscopic filarial worms—microfilariae—circulating in the person’s blood enter and infect the mosquito.

The microfilariae mature into infective larvae within the mosquito, according to WHO.

When the infected mosquito bites another person, the mature parasite larvae would enter the person’s body through the skin and migrate to the lymph vessels where the worms would grow into adult worms and disrupt the normal function of the lymphatic system.

An adult worm could live for about six to eight years. Once these worms mate, millions of microfilariae could be released into the blood — which could then infect another mosquito and continue the cycle of transmission.

“Infection is usually acquired in childhood causing hidden damage to the lymphatic system,” the WHO said.

Signs and symptoms

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said most infected people could be asymptomatic and might never develop clinical symptoms or have no external signs of infection, “despite the fact that the parasite damages the lymph system.”

Graphic by Ed Lustan

According to the Department of Health (DOH), some signs and symptoms of lymphatic filariasis, which occur years after infection, included:

- Fever

- Chills

- Muscle or body aches

- Malaise or weakness

- Swollen lymph nodes

In cases when lymphatic filariasis develops into chronic conditions, symptoms such as lymphoedema (tissue swelling) or elephantiasis (thickening of skin or tissue) of limbs occur.

“Lymphedema is caused by improper functioning of the lymph system that results in fluid collection and swelling,” the US CDC explained.

Although lymphedema usually affects the limbs, it can also cause swelling of the scrotum— also called hydrocele — or affect the breasts and genital organs.

Infected male patients can develop hydrocele due to infection, specifically with the Wuchereria bancrofti.

“The swelling and the decreased function of the lymph system make it difficult for the body to fight germs and infections. Affected persons will have more bacterial infections in the skin and lymph system,” said the US CDC.

“This causes hardening and thickening of the skin, which is called elephantiasis,” it added.

These bacterial infections, the US CDC noted, can be prevented with appropriate skin hygiene and care for wounds.

Aside from the listed symptoms, the filarial infection may also cause tropical pulmonary eosinophilia syndrome — a condition where a person has a higher than the normal level count of disease-fighting white blood cells called eosinophils.

Some symptoms of tropical pulmonary eosinophilia syndrome include:

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

- Wheezing

“The eosinophilia is often accompanied by high levels of Immunoglobulin E ( IgE) and antifilarial antibodies,” the US CDC added.

Stigma

Body deformities, like lymphoedema and elephantiasis, caused by lymphatic filariasis could often lead to social stigma, according to WHO.

The disease, which predominantly affects the rural poor, could also impact the mental health of the infected person and lead to loss of income-earning opportunities and increased medical expenses for both the patient and their caretakers.

“The socioeconomic burdens of isolation and poverty are immense,” the WHO said.

Available treatment

To stop the spread of infection and eliminate lymphatic filariasis globally, the WHO recommends a preventive chemotherapy strategy involving mass drug administration (MDA).

“MDA involves administering an annual dose of medicines to the entire at-risk population,” WHO said.

“The medicines used have a limited effect on adult parasites but effectively reduce the density of microfilariae in the bloodstream and prevent the spread of parasites to mosquitoes,” it added.

Data by the WHO showed that as of 2020, the MDA against lymphatic filariasis is still ongoing in the Philippines.

According to the DOH, there are three types of treatment offered for lymphatic filariasis in the country:

- Selective treatment with Diethylcarbamazine Citrate (DEC) for infected people with clinical manifestations of the disease.

- Mass treatment of people living in established endemic areas.

- Medicines, like DEC and Albendazole (ALB), are administered once a year for five years.

WHO reported that in 2019, 859 million people in 50 countries were living in areas that require preventive chemotherapy to stop the spread of infection.

Graphic by Ed Lustan

In the Philippines, the number of people who require preventive chemotherapy for lymphatic filariasis has decreased from 2015 to 2020, according to figures presented by WHO.

From 18,841,425 in 2015, there were only 1,911,463 people who required preventive chemotherapy for the disease last year in the Philippines.

This was equivalent to 0.221 percent of the global population requiring preventive chemotherapy for lymphatic filariasis in 2020.

The drop in cases of lymphatic filariasis in the Philippines was also evident in the reported number of people who had already received treatment for the disease.

Last year, 1,685,852 infected persons were treated for lymphatic filariasis while 225,611 were not yet covered by the preventive chemotherapy against the disease.

This was at least 10 times lower than the figures recorded in 2015 when 11,095,582 received treatment for the parasitic infection and 7,745,843 were left waiting to be covered by preventive chemotherapy.

The number of districts in the country requiring and implementing preventive chemotherapy for lymphatic filariasis has also decreased to two in 2020.

The WHO’s data showed that the nationwide coverage of preventive chemotherapy for lymphatic filariasis in the Philippines has improved during the past six years.

From 58.89 percent in 2015, 72.66 percent in 2016, 78.88 percent in 2017, 77.69 percent in 2018 and 72.29 percent in 2019 to 80.20 percent in 2020.

Prevention

The DOH suggests the following prevention methods against lymphatic filariasis:

- Wear long sleeve shirt and long pants when working in farms or areas endemic to filariasis.

- Sleep under a mosquito net.

The US CDC recommended basic care to prevent lymphedema from getting worse:

- Carefully wash and dry the swollen area with soap and water every day.

- Raise the swollen arm or leg to move fluid.

- Perform exercises that could help move fluid and improve lymph flow.

- Disinfect wounds and use antibacterial or anti-fungal cream if necessary.

- Wear appropriately-sized shoes to protect feet from injury.