How battle vs Bataan nuke plant was won

‘MONSTER’ IN THEIR MIDST The “Monster of Morong” is how activists call the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant. The facility in Morong, Bataan province, they say, was built on onerous loans, old

design, secrecy, corruption and human rights abuses during the regime of dictator Ferdinand Marcos. —LYN RILLON

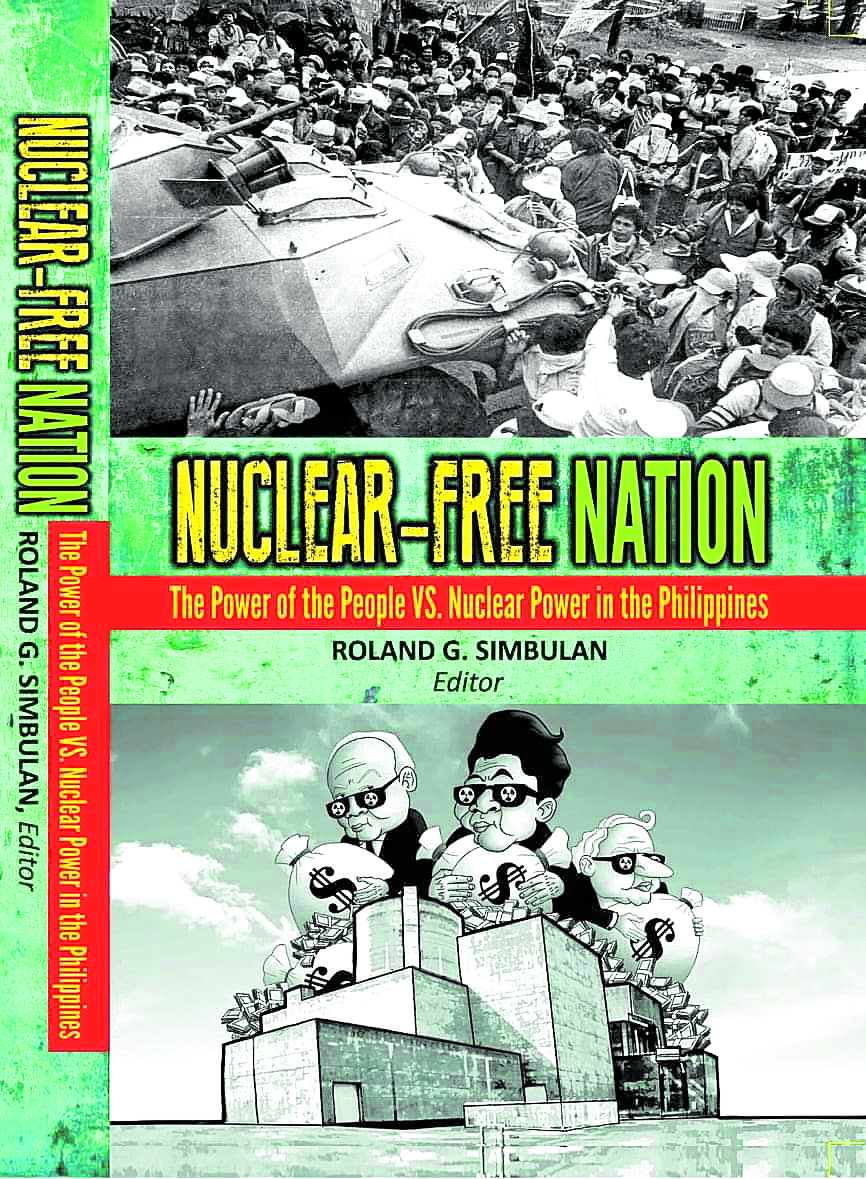

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO, Pampanga, Philippines — “It is the record of our resistance,” says professor Roland Simbulan of the new book he edited, “Nuclear-Free Nation (The Power of the People vs. Nuclear Power in the Philippines).”

The book project started a decade ago but copies are out only this month. “We needed time to step back to sum up and assess our victories and shortcomings for the present and future generations,” Simbulan told the Inquirer.

The 264-page book gives firsthand accounts of what he called a “successful and historic struggle” because aside from editing the book, Simbulan chaired the Nuclear-Free Philippines Coalition (NFPC) seven years after its founding on Jan. 26, 1981.

The book is dedicated in memory of NFPC founding chair, the late former Sen. Lorenzo Tañada, founding secretary general Rev. Jose Cunanan (who died on Oct. 12 at 81), and many others including martyrs like Bataan Nuclear Power Plant (BNPP) worker Ernesto Nazareno who disappeared in 1978.

“How Filipinos stopped the BNPP and nuclear power in the country is a great story,” Simbulan, 67, wrote in the introduction. “We owe it to future generations, for whom this book is written. It is a commitment to promote a nuclear-free homeland for the survival of human life.”

Article continues after this advertisementIn this narrative, the claim was: “The Philippines’ grassroots antinuclear movement—even under the most repressive conditions of martial rule in the 1970s and 1980s and up to the present—has made sure that not a single nuclear power plant operates on the Philippine archipelago.”

Article continues after this advertisementThe late Kaka Calimbas added truth to that, relating that Morong farmers and workers in the then Bataan Export Processing Zone in nearby Mariveles town were the first ones to fight the BNPP.

Beginnings

Cathy Alcantara, a victim of extrajudicial killing when Maj. Gen. Jovito Palparan commanded the military in Central Luzon in 2005, recounted before her death that “no person in the Bataan communities was left uninformed about the issue.”

The antinuclear movement began as a desk of the Citizens’ Alliance for Consumer Protection based in St. Scholastica’s College in Manila that transformed into a coalition of 129 organizations in 1981.

That was how the Benedictine nun, Sister Aida Velasquez, a chemist, was drawn to what later became the NFPC.

Scientific information showed to be important to key leaders, US-based Filipino chemist Dr. Jorge Emmanuel noted.

“Westinghouse filed an application for an export license with the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission in November 1976. A few months earlier, residents of Morong, Bataan, assisted by a local Methodist minister and Sister Aida tried to find out about the nuclear plant project. They were answered with threats by the military. Unable to obtain information, Sister Aida and others reached out to technical specialists and Filipino support groups in the United States,” Emmanuel wrote.

Msgr. Antonio Dumaual, then parish priest of Morong, said they fought the BNPP “not on mere abstracts.”

During the campaign, they raised questions on corruption, choice of site, old design, faulty construction as well as safety of the people and the environment.

As bank documents revealed, the BNPP became the “single largest fraudulent loan and project” of the administration of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos because by the time it was completed in December 1984, the cost reached $2.3 billion, or four times the initial bid of $500 million.

Apart from popularizing the issues in many forms, NFPC used songs, poems and theater productions to bring home the messages. They also fought the BNPP up to the Supreme Court.

Completed in 1984, the BNPP was scheduled for operations with the loading of the uranium fuel but the NFPC stopped this in the “nick of time” through the Welgang Bayan (People’s Strike) on June 18 to June 20, 1985. Veterans of that protest said transportation was paralyzed, many businesses closed, work halted and sympathizers from Metro Manila and nearby provinces joined Bataan folk to express a united voice against the BNPP despite threats from the military.

Lawyer Dante Ilaya, Nuclear-Free Bataan Movement chair, noted that the strike proved to be a prelude to the People Power revolt on Edsa that helped oust Marcos in February 1986.

“So, if we look at the Welgang Bayan, this was a concrete manifestation of people power,” he said.

His group’s organizing was done in the barangay, with residents believing that the BNPP would “endanger their livelihood, their families and communities.”

Simbulan said: “The idea was to create a constituency that would say no to the government that insisted on adopting the nuclear option to solve its energy problem, and linking this with the risks entailed in storing and transiting nuclear weapons in the US military bases.”

Filipinos abroad and foreigners joined the cause, adding international pressures on Marcos.

The National Union of Scientists found more than 4,000 technical defects. These and the Chernobyl nuclear disaster played parts in the decision of then President Corazon Aquino to mothball the BNPP and for then President Fidel Ramos to uphold Aquino’s decision in 1993.

Shortly after proposals were made to revive the BNPP, nuclear disasters occurred, the latest in Fukushima, Japan, in 2011.

“Let us also say, we had ‘divine assistance.’ When they started the BNPP construction, the Three Mile Island [in Pennsylvania, United States] disaster happened. Then, at the height of the antinuke struggle in 1986, Chernobyl [in Ukraine] exploded. Now, when [former Pangasinan] congressman Mark Cojuangco came around, wanting to recommission the mothballed nuclear plant, the Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster happened. So, like I said, we are guided by Someone up there,” Dumaual said.

US campaign

For Emmanuel, the campaign of US-based Filipinos and their allies like the Friends of the Filipino People in Philadelphia, contributed by “uncovering the extent of technical recklessness, expanding global awareness about the notorious plant, and demonstrating the value of international solidarity.”

They helped also in the lobby to repudiate the BNPP loans, which incurred an interest of $355,000 a day.

Emmanuel still has unanswered questions: “As I look back at the BNPP case, I am shocked at how far the nuclear madness went, like an illness that could have been stopped sooner but was allowed to persist until it spiraled out of control. How could officials not see the deficiencies of the plant and its placement even after the evidence was brought to light? Why did government officials responsible for protecting the people’s interest allow the country to be fleeced over and over? How could they agree to financial arrangements so onerous on the Filipino people? Why did decision-makers turn a blind eye on bribery, corruption and human rights abuses?”

NFPC activists helped prohibit nuclear weapons in any part of Philippine territory through a provision in the 1987 Constitution. This ban was made one of the bases of voting to close US military camps in the Philippines in 1991.

There is a chapter on the views of two BNPP executives but theirs are of regrets.

Said Mauro Marcelo, National Power Corp. (NPC) and BNPP quality assurance engineer: “I still believe that nuclear power is feasible for the Philippines. We had passed the most difficult stage of the program and our economy could have been like South Korea now if we were able to operate the BNPP in 1986. South Korea and the Philippines entered the nuclear program almost at the same time, but we stopped in 1986 while South Korea continued.”

Carmelito Tatlonghari, NPC/BNPP radiation controls superintendent, shared: “When the BNPP was mothballed in 1986, the plant operating personnel felt as if they were broken wreckages of humanity, for they have spent the prime time of their lives preparing for the operation of the BNPP. And now, they are too young to retire, and too old to land a new job. Their career paths have gone astray.”

But Simbulan issued a warning: “The nuclear power industry in Asia, even in the aftermath of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, has not given up its plans. This is even after it has been proven by the most recent authoritative sources that solar power is the cheapest form of energy today and in the future … Here in the Philippines, the Department of Energy and the Department of Science and Technology have not given up their plans to use nuclear energy as long-term energy options. They think that the BNPP project in the Philippines failed only because there was a ‘communications problem’ or that it lacked a ‘public relations campaign.’”

(Editor’s Note: “Nuclear-Free Nation” is available at Popular Bookstore, PGX Fair Trade Market, Central Books Supply and Solidaridad Bookshop)