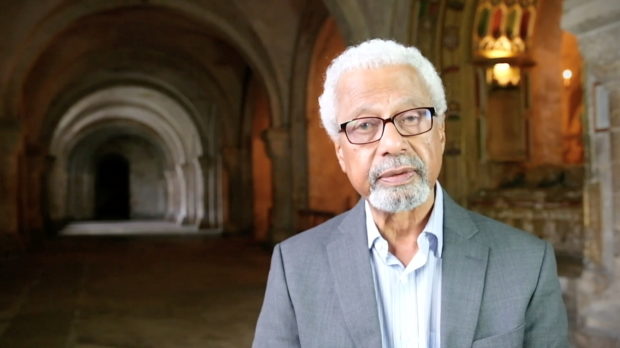

Abdulrazak Gurnah reads for a Canterbury Cathedral project in Canterbury, Britain June 2021, in this screen grab obtained from a social media video. Video recorded in June 2021. (REUTERS)

STOCKHOLM – Tanzanian novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah won the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee,” the award-giving body said on Thursday.

Based in Britain and writing in English, Gurnah, 72, joins Nigeria’s Wole Soyinka as the only two non-white writers from sub-Saharan Africa ever to win what is widely seen as the world’s most prestigious literary award.

His novels include “Paradise”, set in colonial East Africa during World War One and short-listed for the Booker Prize for Fiction, and “Desertion.”

“Gurnah’s itinerant characters in England or on the African continent find themselves in the gulf between cultures and continents, between the life left behind and the life to come,” Anders Olsson, head of the Swedish Academy’s Nobel Committee for Literature, told reporters.

“I dedicate this Nobel Prize to Africa and Africans and to all my readers. Thanks!” Gurnah tweeted after the announcement.

Gurnah told Reuters by telephone that the prize was “such a complete surprise that I really had to wait until I heard it announced before I could believe it.”

He left Africa as a refugee in the 1960s amid the persecution of citizens of Arab origin on the Indian Ocean archipelago of Zanzibar, which would unite with the mainland territory Tanganyika to form Tanzania. He was able to return only in 1984, seeing his father shortly before his death.

His selection for the top honour in literature comes at a time of global tensions around migration, as millions of people flee violence and poverty in places such as Syria, Afghanistan and Central America, or are displaced by climate change, often taking tremendous risks during their passages.

Olsson said the committee’s choice was not a response to recent headlines, and it had been following Gurnah’s work for years.

In an interview later on Thursday with Reuters, Gurnah, however, expressed amazement at the resolution and courage of those who travelled so far to escape their own countries for a new life.

“This somehow is constructed as if it’s immoral – you know they use this phrase ‘economic migrant’ – as if to be an economic migrant is some kind of crime. Why not?”

“Millions of Europeans over centuries left their homes for precisely that reason and invaded the world for precisely for that reason,” he said in his garden in the English city of Canterbury.

‘CONSCIOUSLY BREAKS CONVENTION’

Though Swahili was his first language, English became Gurnah’s literary tool when he began writing at the age of 21.

He has drawn inspiration from Arabic and Persian poetry as well as the Koran, but the English-language tradition, from William Shakespeare to V.S. Naipaul, would especially mark his work, the Swedish Academy said.

“That said, it must be stressed that he consciously breaks with convention, upending the colonial perspective to highlight that of the indigenous populations,” said the academy, a 235-year-old Swedish language institute which awards the prize and the 10 million Swedish crowns ($1.14 million) that go with it.

This was the second straight year that the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to a writer in English, and the fourth of the last six, an unusually long stretch for the prize to be dominated by a single language.

In an interview with the Academy, Gurnah said many Europeans misunderstood the idea of migration.

“When many of these people who come, come out of both need, and also because, quite frankly, they have something to give,” he said. “They don’t come empty-handed. A lot of them are talented, energetic people who have something to give.”

“So that might be another way of thinking about it. You are not just taking people in as if they are poverty-stricken nothings.”

Eliah Mwaifuge, a professor of literature at Tanzania’s University of Dar es Salaam, said Gurnah “truly deserves this award,” although the writer’s work was better known abroad than in Tanzania itself.

‘FEARLESS UNDERSTANDING’

Peter Morey, a professor in the University of Birmingham’s Department of English Literature, singled out Gurnah’s “fearless understanding of the connections between people and places and how they change over time in the face of the boundaries and borders designed to keep them apart.”

“In one of his novels he describes the memory of the exile as being ‘a dim, gutted warehouse with rotting planks and rusted ladders where you spend time rifling through abandoned goods,'” Morey said.

Since Soyinka became the first African to win the prize in 1986, it has been won by Egypt’s Naguib Mahfouz and three white African writers – South Africans Nadine Gordimer and J.M. Coetzee, and Doris Lessing, who was raised in British-ruled Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

Past winners have primarily been novelists such as Ernest Hemingway, Gabriel Garcia Marquez and Toni Morrison, poets such as Pablo Neruda, Joseph Brodsky and Rabindranath Tagore, or playwrights such as Harold Pinter and Eugene O’Neill.

But writers have also won for bodies of work that include short fiction, history, essays, biography or journalism. Winston Churchill won for his memoirs, Bertrand Russell for his philosophy and Bob Dylan for his lyrics. Last year’s award was won by American poet Louise Gluck.

Beyond the prize money and prestige, the Nobel literature award generates a vast amount of attention for the winning author, often spurring book sales and introducing less well-known winners to a broader international public.