Yet another challenging year for public school teachers

BACK TO NEW NORMAL Rowena Peñalosa, who teaches Grade 3 students at Melencio M. Castelo Elementary School in Quezon City, appears to have prepared everything for Monday’s opening of remote learning in public schools. —NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

(First of two parts)

A month before the opening of the second school year in a worsening health crisis, teacher Sarah says she already knew it will be “another challenging year.”

Sarah, 51, has worked more than 500 days under the remote learning setup, and she expects the same problems, including unclaimed or undelivered learning modules and thousands of pesos out of her own pocket.

“Distance learning has not brought anything good to us teachers a year later,” says Sarah, a public school teacher at Balongbalong Elementary School in Zamboanga del Sur province who asked for anonymity.

In the past school year, Sarah was mortified to see her home gradually morph into a makeshift office.

Article continues after this advertisementFor one, the bedroom that was her oasis from her busy teaching life now serves as storage area for piles of unchecked modules and unfinished reports.

Article continues after this advertisementInstead of relaxing at night, as she did before the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closure of schools early in 2020, she lies awake, worrying about the students lagging behind and the household chores needing attention.

“Never in my life did I expect my profession to get to this point,” Sarah says.

Overworked, underpaid

The Department of Education (DepEd) declared the “successful” resumption of classes on Oct. 5, 2020, but in the shadow of the celebration, public school teachers were crying for help.

With an education system faulty to begin with, a haphazardly implemented remote learning setup has left the overworked and underpaid teachers to fend for themselves.

Prior to the 2020 school opening, Sarah recalls, teachers in her school were required to attend virtual meetings as early as April to gauge their skills in crafting self-learning modules.

And as this year’s school opening neared, teachers were called to the DepEd’s Oplan Brigada Eskwela, a national activity aimed at prioritizing preparations and “strengthening partnership engagement to ensure that quality basic education will continue despite the challenges posed by COVID-19.”

Only a few weeks earlier, they supervised virtual graduation ceremonies.

In July and August, they accomplished student assessments.

The previous school year was originally set to end on June 11, but the DepEd extended this twice before finally settling on July 10 to give way to the annual in-service training for teachers.

Intense workload

The extended school year meant an intense workload, as testified to by 85.2 percent of 1,278 respondents in a survey conducted on June 25 to July 2 by the Movement for Safe, Equitable, Quality and Relevant Education (SEQuRE).

The majority noted a heavier workload under distance learning, with new challenges quickly arising.

The inaccessible internet (experienced by 92.5 percent of the survey respondents), scarcity of gadgets, and mounting paperwork were problems they grappled with daily.

They lamented the dearth of government support, a perennial challenge made worse by the pandemic.

Sarah, who lives on a mountainside, says she stays up until 2 a.m. to wait out the internet rush just so she can submit reports to the schools division office (SDO) and contact her students.

Other teachers in more remote areas travel at least an hour to reach the town proper, where there is a better internet signal.

“As [a teacher], I don’t just do that occasionally; I do that on a daily basis.

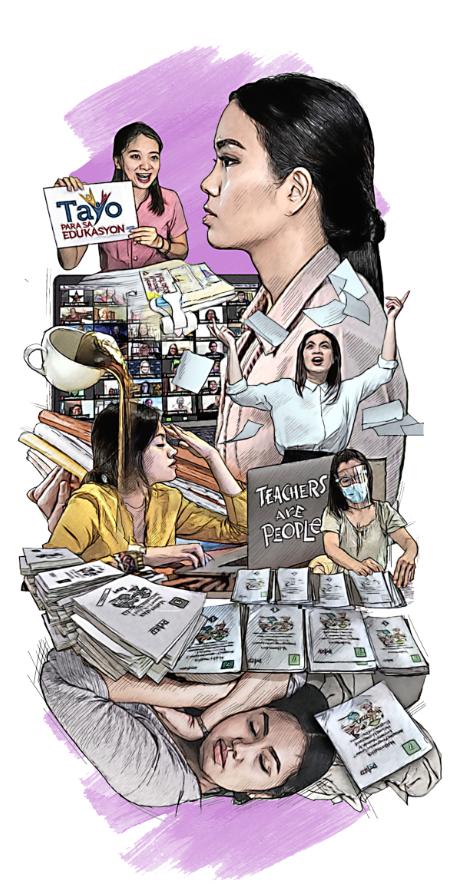

MORE TIME TO REST Many teachers anticipate the same heavy workload under remote learning in this school year, but with fresh challenges arising. —ILLUSTRATION BY RENE ELEVERA

If the SDO requires us to submit reports, I need to stay up late just so my cell phone has a stable internet connection,“ Sarah says.

No work-life balance The reports include performance evaluation portfolios, learners’ performance reports, summaries of quarterly assessments, and school-based management documents, etc.

Sometimes, Sarah says, teachers are told to accomplish and submit multiple reports at a time, depriving them of rest periods.

Liza Marie Campoamor Olegario, an education psychologist and the research head of SEQuRE, warns that many educators no longer have a work-life balance, as they have to juggle household chores and schoolwork.

It is a problem encountered by three out of 10 teachers.

“Before the pandemic, teachers rarely took their work home. Now, their work overlaps with household duties.

How are you going to deal with this? It’s [through] a lighter workload,” says Olegario, a faculty member of the University of the Philippines’ College of Education.

“People need to remain sane; they need to take breaks for their mental health.

Otherwise, they will become unproductive,” she adds.

SIM cards

In July, the DepEd announced that it would distribute SIM cards with connectivity load to 1 million teaching and nonteaching personnel in public schools as part of its “promises” in the Bayanihan to Recover As One Act, the government’s second stimulus package in its fight against the pandemic.

By Aug. 24, the DepEd said, it had distributed SIM cards to 277,381 personnel, who were each given a total of 102 gigabytes of mobile data to be used and rationed over three months.

But the Alliance of Concerned Teachers cited reports from field offices that teachers still had trouble using the SIM cards due to poor reception in their areas, and that others had not received any.

Sarah herself says she has yet to receive a SIM card. She shells out P1,500 a month for her communication expenses. Under the 2022 National Expenditure Program, the DepEd’s proposed budget of P1.37 trillion was cut by 53.87 percent to P629 billion.

Of the total, P11.65 billion will go to the DepEd’s computerization program that will provide “appropriate technologies”—including IT infrastructure, networking facilities and “various information systems”—to public schools.

But the hardships of teachers cannot be eased by additional telco infrastructure alone. They also need support for nonacademic tasks like distributing and collecting learning materials.

Boats and horses

In Barangay Balongbalong’s community of fishers and farmers, most parents did not complete their own schooling or cannot find the time in their daily toil to guide their children’s learning.

Thus, public school teachers go house to house to distribute and collect learning modules, on top of endless paperwork.

To reach their students in neighboring islets, some teachers in Sarah’s school ride pump boats; others whose students live in the mountains travel on horseback.

While some parents manage to spare a few hours to supervise their children, those who stopped schooling at a lower grade level run the risk of dispensing incorrect guidance. Teachers recognize this reality and, as a result, repeat lessons for their struggling students.

This was the sentiment of teachers who took part in four rounds of focus group discussions conducted by Aral Pilipinas, a coalition of education stakeholders, professionals and civil society groups advocating education continuity amid crises.

“Who will help the students if their parents cannot teach them? … If parents incorrectly teach lessons to their children, then this again adds extra hours to a teacher’s workload,” says Aral Pilipinas lead convener Reg Sibal.

In their May 2020 position paper titled “Ensuring Education Continuity in the Time of COVID-19,” researchers from Aral Pilipinas and The Asia Foundation note that the teachers’ workload may be eased by the hiring of personnel for nonacademic tasks.

“Additional manpower is always helpful in terms of teaching because class sizes have already been a problem even before [the pandemic],” Sibal says.

Top-down approach

Education Secretary Leonor Briones and other DepEd officials have insisted that “there is no one-size-fits-all solution” in implementing different modes of learning.

But the DepEd’s “top-down” implementation of distance education policies has not done any good for public school teachers, especially those in remote areas with limited resources for learning continuity.

“The problem with the top-down approach is that what is applied in Metro Manila is also applied in the provinces. That’s where you can see the difficulty in policy implementation,” Olegario says.

To concretely address the teachers’ plight, the government must take a “bottom-top” approach and look at solutions from the grassroots, she says. In this way, the challenges teachers face can be better contextualized, and, at the same time, they can offer solutions themselves.

“Experts coming from the grassroots can collaborate among themselves and offer solutions based on their situation,” Olegario notes, adding that schools may select their “best teachers” to craft better policies.

Better prepared

For all their difficulties, public school teachers are now better prepared for another year—possibly more—of remote learning.

Last year, they were caught by surprise and had to scramble to produce modules, meet with parents virtually, and attend hourslong webinars to prepare for remote learning, which may be enforced for years.

But Sibal clarifies that while teachers have adjusted to their new reality even with unjust compensation, the public must temper its expectations.

“Let us look at what we are expecting our teachers to do in this challenging time.

Once we bombard them with tasks, we forget that they should also have time to rest and prepare for other things,” she says.

Sarah longs for the days when she had time to sing her favorite tunes as a way of unwinding—now impossible with the heavy workload. She admits that for the first time in her nearly 30 years of teaching, she sometimes considers quitting due to the overwhelming stress. But she has chosen to stay, to continue fighting for quality and equitable education. “I call on my fellow teachers to be still, and not to forget to take breaks every once in a while … It has been stressful for us, but let us never lose hope,” Sarah says.