40 years after leak, the Pentagon Papers are out

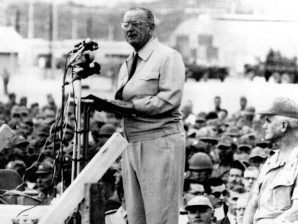

In this October 1967 file photo President Lyndon B. Johnson talks to troops at Cam Ranh Bay, South Vietnam, during the Vietnam War. At right is Gen. William Westmoreland. AP Photo, File

WASHINGTON — Four decades ago, a young defense analyst leaked a top-secret study packed with damaging revelations about U.S. conduct of the Vietnam War. On Monday, that study, dubbed the Pentagon Papers, finally came out in complete form. It is a touchstone for whistleblowers everywhere and just the sort of leak that gives presidents fits to this day.

The documents show that almost from the opening lines, it was apparent that the authors knew they had produced a hornet’s nest.

In his Jan. 15, 1969, confidential memorandum introducing the report to the defense chief, the chairman of the task force that produced the study hinted at the explosive nature of the contents. “Writing history, especially where it blends into current events, especially where that current event is Vietnam, is a treacherous exercise,” Leslie H. Gelb wrote.

Asked by Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara to do an “encyclopedic and objective” study of U.S. involvement in Vietnam from World War II to 1967, the team of three dozen analysts pored over a trove of Pentagon, CIA and State Department documents with “ant-like diligence,” he wrote.

Their work revealed a pattern of deception by the Lyndon Johnson, John Kennedy and prior administrations as they secretly escalated the conflict while assuring the public that, in Johnson’s words, the U.S. did not seek a wider war.

Article continues after this advertisementThe National Archives released the Pentagon Papers in full Monday and put them online, long after most of the secrets spilled. The release was timed 40 years to the day after The New York Times published the first in its series of stories about the findings, on June 13, 1971, prompting President Richard Nixon to try to suppress publication and crush anyone in government who dared to spill confidences.

Article continues after this advertisement

In this Nov. 25, 1972, file photo President Nixon confers with his adviser Henry Kissinger, right, after Kissinger's return from a week of secret negotiations in Paris with North Vietnam's Le Duc Tho. Forty years after the explosive leak of the Pentagon Papers, a secret government study chronicling deception and misadventure in U.S. conduct of the Vietnam War, the full report is being released Monday, June 13, 2011. The report was leaked primarily by foreign policy analyst Daniel Ellsberg, in a brash act of defiance that stands as one of the most dramatic episodes of whistleblowing in U.S. history. Ellsberg served with the Marines in Vietnam and came back disillusioned. He was a protégé of Kissinger's, who called the young man his most brilliant student. AP Photo/File

Prepared near the end of Johnson’s term by Defense Department and private analysts, the report was leaked primarily by one of them, Daniel Ellsberg, in a brash act of defiance that stands as one of the most dramatic episodes of whistleblowing in U.S. history.

As scholars pore over the 47-volume report, Ellsberg said the chance of them finding great new revelations is dim. Most of it has come out in congressional forums and by other means, and Ellsberg plucked out the best when he painstakingly photocopied pages that he spirited from a safe night after night, and returned in the mornings.

He told The Associated Press the value in Monday’s release was in having the entire study finally brought together and put online, giving today’s generations ready access to it.

The Pentagon Papers chronicle failures of U.S. policy at seemingly every turn. One was a focused attempt from 1961 to 1963 to pacify rural Vietnam with the Strategic Hamlet Program, combining military operations to secure villages with construction, economic aid and resettlement.

The report concludes the U.S. had not learned lessons of the past, namely that peasants would resist attempts to change the pattern of their lives. The hamlet program “was fatally flawed in its conception by the unintended consequence of alienating many of those whose loyalty it aimed to win,” it said.

At the time, Nixon was delighted that people were reading about bumbling and lies by his predecessors, which he thought would take some anti-war heat off him. But if he loved the substance of the leak, he hated the leaker.

He called the leak an act of treachery and vowed that the people behind it “have to be put to the torch.” He feared that Ellsberg represented a left-wing cabal that would undermine his own administration with damaging disclosures if the government did not make him an example for all others with loose lips.

It was his belief in such a conspiracy, and his willingness to combat it by illegal means, that put him on the path to the Watergate scandal that destroyed his presidency.

Five burglars broke into the Washington headquarters of the Democratic National Committee in the Watergate building on June 17, 1972, apparently to install clandestine electronic monitoring devices. The burglary led to evidence of widespread wrongdoing within the Nixon White House and the eventual demise of the administration with Nixon’s resignation on Aug. 8, 1974.

Nixon’s attempt to avenge the Pentagon Papers leak failed. First the Supreme Court backed the Times, The Washington Post and others in the press and allowed them to continue publishing stories on the study in a landmark case for the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which, among other things, guarantees freedom of the press. Then the government’s espionage and conspiracy prosecution of Ellsberg and his colleague Anthony J. Russo Jr. fell apart, a mistrial declared because of government misconduct.

The judge threw out the case after agents of the White House broke into the office of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist to steal records in hopes of discrediting him, and after it surfaced that Ellsberg’s phone had been tapped illegally. That September 1971 break-in was tied to the Plumbers, a shady White House operation formed after the Pentagon Papers disclosures to stop leaks, smear Nixon’s opponents and serve his political ends.

The next year, the Plumbers were implicated in the Watergate break-in.

Ellsberg remains convinced the report — a thick, often tough read — would have had much less impact if Nixon had not temporarily suppressed publication with a lower court order and had not prolonged the headlines even more by going after him so hard. “Very few are going to read the whole thing,” he said in an interview, meaning both then and now. “That’s why it was good to have the great drama of the injunction.”

The declassified report includes 2,384 pages missing from what was regarded as the most complete version of the Pentagon Papers, published in 1971 by Democratic Sen. Mike Gravel. But some of the material absent from that version appeared — with redactions — in a report of the House Armed Services Committee, also in 1971.

One volume missing from the Gravel edition and released Monday details U.S. miscues in training the Vietnamese National Army from 1954 to 1959. The U.S. sent more than $2 billion in aid to Vietnam then, nearly 80 percent for security.

In words that echo today’s laments about money misspent in Iraq and Afghanistan, the report says the U.S. did not get much in return. “Very little has been accomplished,” the volume says.

Bureaucratic compromises between the Pentagon and State Department also undermined the training program in Vietnam, according to the document. Increasingly, the U.S. was “selecting the least desirable course of action.”

The 40th anniversary provided a motivation for government archivists to declassify the records. “If you read anything on the Pentagon Papers, the last line is always, ‘To date, the papers have yet to be declassified by the Department of Defense,'” said A.J. Daverede, director of the production division at the National Declassification Center. “It’s about time that we put that to rest.”

The center, part of the National Archives, was established by a 2009 executive order from President Barack Obama, with a mission to speed the declassification of government records.

If not with the same personal vendetta, presidents since Nixon have acted aggressively to tamp down leaks. Obama’s administration has pursued cases against five government leakers under espionage statutes, more than any of his recent predecessors.

Most prominent among the cases is that of Pfc. Bradley E. Manning, an intelligence analyst accused of passing hundreds of thousands of military and State Department documents to WikiLeaks. The administration says it provides avenues for whistleblowers to report wrongdoing, even in classified matters, but it cannot tolerate unilateral decisions to release information that jeopardizes national security.