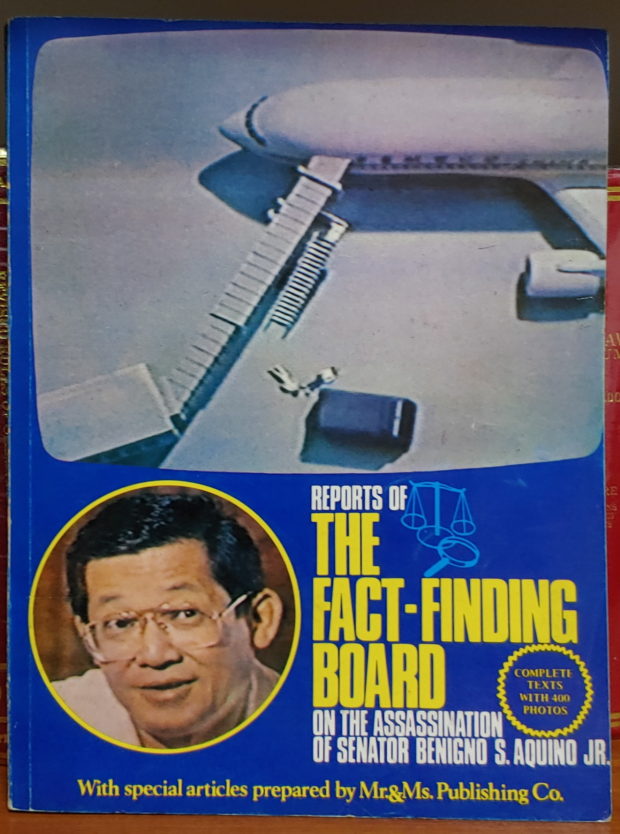

FACT-FINDING The 420-page book published in October 1984 contains the report of the majority members of the fact-finding board headed by retired Court of Appeals Justice Corazon Agrava and her own “minority report.” —PHOTO COURTESY OF OLIVER TEVES

MANILA, Philippines The Agrava Fact-Finding Board’s conclusion that the assassination of former Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. 38 years ago, was a military conspiracy, not a communist plot as dictator Ferdinand Marcos had insisted, should remind Filipinos of the continuing struggle between truth and lies in this country.

“The Agrava report remains relevant because we know how lies are [still] being peddled, very systematically,” said Aquino’s nephew, Rafael Lopa, president and executive director of Ninoy and Cory Aquino Foundation.

“With the entry of technology and … social media, there will be those who will be proactive in perpetuating lies,” he said in a Zoom interview. These include glowing claims of progress under the Marcos dictatorship and the sordid tales about his uncle.

“The world of technology is being used as a weapon against the truth about the martial law years and the assassination,” he said.

Attempts to revise history are using funds “stolen from us, never returned and now being used for this deliberate act of lying,” Lopa said.

Seminal event

In one forum related to the assassination that she attended before the pandemic, former Inquirer national security and political reporter Fe Zamora was struck by the questions of some students on whether Aquino was a communist.

“Revisionism is so strong,” she said. “Social media plays a big part in this — fake news and disinformation. YouTube for example has a lot of fake videos.”

The Aug. 21, 1983, assassination of Aquino was a seminal event in the country’s history that triggered massive protests against not just the killing of the opposition leader but also against oppression and plunder during the Marcos dictatorship.

Former Sen. Rene Saguisag told the Inquirer by email that the Agrava report “inaugurated the parliament of the streets and the people finally, peacefully, powered to victory and liberation on Feb. 25, 1986.”

The 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution drove the Marcoses out of Malacañang. Lopa, who was then a junior college student, said the Agrava report was one of those rare efforts that in the end served justice during a period of oppression.

Shortly after Aquino and his supposed assassin Rolando Galman were killed that Sunday afternoon, Marcos held a news conference saying that his government had no hand in Aquino’s death and that it was a “rubout job” by the communists who wanted to embarrass his regime.

Divided on plotters

Still, three days later, he created a fact-finding board led by then Chief Justice Enrique Fernando to investigate the assassination.

The Fernando board conducted several hearings and ocular inspections before all five members resigned due to widespread criticism of its questionable impartiality because of the chief justice’s alleged closeness to Marcos.

Marcos then appointed a new board chaired by retired appellate court Justice Corazon Agrava. The other members were Luciano Salazar, Amado Dizon, Dante Santos, and Ernesto Herrera, who was later elected senator.

A year after it was formed, the Agrava board concluded that the military conspired to kill Aquino, but its members were divided on how high up the hierarchy of the Armed Forces were the plotters.

The majority — Salazar, Dizon, Santos, and Herrera — rejected the military’s claim of a communist plot, citing the “irreconcilable contradiction” between the version given by the military and civilian witnesses who, “despite fears of their own personal safety … still gave testimony.”

What is now referred to as the majority report included Marcos’ longtime aide, chief of staff Gen. Fabian Ver, among those “indictable for the premeditated killing” of Aquino.

Agrava’s separate minority report exonerated Ver. She explained that even if he had command responsibility as the military chief, “it will not make him an actual plotter.”

Aside from Ver, the majority report submitted to Marcos on Oct. 24, 1984, listed 25 others involved in the conspiracy to kill both Aquino and Galman: Maj. Gen. Prospero Olivas, Brig. Gen. Luther Custodio, Col. Arturo Custodio, Col. Vicente Tigas, Capt. Felipe Valerio, Capt. Llewelyn Kavinta, Capt. Romeo Bautista, 2Lt. Jesus Castro, Sergeants Pablo Martinez, Tomas Fernandez, Arnulfo de Mesa, Claro Lat, Filomeno Miranda, Rolando de Guzman, Ernesto Mateo, Rodolfo Desolong, Leonardo Mojica, Pepito Torio, Armando dela Cruz and Prospero Bona; Cadet First Class Rogelio Moreno and Mario Lazaga; Airman First Class Cordova Estelo and Aniceto Acupido, and businessman Hermilo Gosuico, the lone civilian.

They were charged the following year with double murder in the Sandiganbayan, but were all acquitted in December 1985.

In September 1986, the Supreme Court decided to allow the conspirators to be tried again, ruling that there would be no double jeopardy on the accused because the first was a “mock trial” ordered by “the authoritarian president” himself.

At the end of the second trial in September 1990, the Sandiganbayan found 16 military men, including General Custodio, guilty and sentenced them to life imprisonment. Ver had fled the country with the Marcoses and died in 1998 in Thailand.

Taboo of the times

Zamora said the Agrava board’s reports on the assassination was groundbreaking at the time.

“Imagine people coming out and saying ‘I saw soldiers shoot Ninoy.’ That was taboo and the findings, when released, were groundbreaking in the sense that people were encouraged to say the truth finally,” she said. “There were a lot of lawyers, prosecutors, fellow journalists who really went all out against the Marcos administration. There was no communist conspiracy and people wanted to narrate what they knew.”

Unlike present-day congressional inquiries, the board hearings in the Magsaysay Hall of the SSS building in Quezon City were not covered on live television, but the government TV network recorded them on video.

As the public started growing weary about the possible outcome of the longdrawn investigation under an administration hostile to the murder victim, a joke circulated around the country that only five people in the Philippines—the members of the board—did not know who killed Aquino.

The fact-finding board took testimonies from 193 civilian and military witnesses, including foreign journalists who accompanied Aquino to Manila, airport employees, Galman’s relatives, supposed members of the New People’s Army (NPA) and even communist party leader Jose Maria Sison who was then in military custody—and Imelda Marcos.

The former first lady, who testified on her 55th birthday on July 2, 1984, tearfully recounted that she personally spoke with Aquino on May 21, 1983, to convince him not to return until an alleged communist plot to kill him had been neutralized. It was the last time she saw him.

“Again, I tried to save his life,” she said. It was the second time she tried to save his life, she said, according to a report from United Press International (UPI).

In 1980, after learning that Aquino had a life-threatening heart condition, Imelda convinced her husband to let Aquino leave for the United States for medical treatment.

To the question of whether she knew who killed Aquino, Imelda replied: “Only God knows,” UPI reported. After she finished testifying, Agrava led those present in singing her the “Happy Birthday” song.

Although there were witnesses who took turns linking Aquino and Galman to the communist movement, the fact-finding board disproved the allegations. In his testimony, Ver said that based on intelligence reports the NPA wanted Aquino dead and that Galman was known in the NPA as “Ka Bert Ramos.”

Ver told the board that Galman shot Aquino when the ex-senator was already on the tarmac, as indicated by the trajectory of the bullet going upward. Earlier reports, however, said the bullet entered the back of Aquino’s head and exited through his chin, suggesting that he was shot by someone slightly above him while still on the stairs to the tarmac.

Mr. & Ms project

Many could not believe the military’s account that an armed rebel had managed to slip through the tight security cordon at the airport and around Aquino’s plane and shoot the former senator.

One photo provided by Japanese journalist Kiyoshi Wakamiya of the scene at the airport tarmac was considered by the board “to be the most significant in its possession, and it raised a lot of questions about the military version,” of the assassination.

Sandra Burton of Time magazine, left her recorder running when Aquino left the plane. Only 10 seconds had elapsed from the time Aquino passed through the plane door when the first shot was recorded “very loud, clear and seemed to be quite close.”

It was also Burton’s recorder that caught the words “Ako na, ako na,” “Eto na, eto na,” and “Pusila, pusila.”

Mr. & Ms. Publishing Company put the majority and minority reports together in a book, along with profiles of the people who testified or had played a role in the investigation.

The late Inquirer editor in chief Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc wrote that no section in the book was “devoted to the discussion of the motive for the crime.”

“But why would the military kill Aquino? The reports do not say. Perhaps they do not wish to say for sure, in this country of dangerous uncertainties. And their not wanting to say it indicates that we have a long way to go before we are rid of our horrors,” she said in her introduction to the book released in October 1984.

“Perhaps there is no need to investigate and discuss the obvious,” Magsanoc said. “And it is best that the motive is left unsaid and consigned to the judgment of history.”