Lockdowns in PH: A brief history

Police checks, like this last year, have become common sights during lockdown enforcement. FILE PHOTO/NINO JESUS ORBETA

MANILA, Philippines—The latest lockdown looming over the National Capital Region (NCR) would be the fourth in the capital, which accounts for more than half of the Philippine economy.

As more than 12 million residents await the latest round of restrictions to start on Aug. 6 and end on Aug. 20, they are told that limiting their movement is the price to pay for preventing a bigger tragedy—coronavirus infections running out of control.

The measures appear to be tilted in favor of just one aspect of the crisis—health—and neglectful of the other one: economy and livelihood. Some experts are saying that protecting people against getting sick and from losing their livelihood is not necessarily an either-or proposition.

Disease experts had shown that keeping people apart was an effective way to slow transmission of the virus for a basic reason. Humans are the virus’ main carriers.

“The principal mode by which people are infected with SARS Cov2 is through exposure to respiratory fluids carrying infectious virus,” said the US Centers for Disease Control in its many advisories about COVID-19.

According to CDC, people get infected mainly through:

- Inhaling microscopic respiratory droplets and aerosol particles carrying the virus

- Getting the virus in the mouth, nose or eye from splashes or sprays of virus-laden particles from an infected person

- Touching contaminated mucous membranes or surfaces

There are still inconclusive studies saying the virus is airborne which could be alarming but have not been shown to be certain.

The experts are sure about one thing, though. Close human contact increases the risks of infection, which would make lockdowns an essential weapon in fighting SARS Cov2.

At one of his briefings on the government’s COVID response, President Rodrigo Duterte blurted out how difficult it would be to keep people safe distances apart in a place as crowded as Metro Manila.

On this, Duterte was correct. Metro Manila is one of the most densely populated urban areas in the world. In Manila alone, there are at least 71,263 persons per square kilometer, according to census data in 2015. In Mandaluyong City, the density is 41,580 persons per sq km. In Pasay City, it’s 29,815 persons per sq km.

Locking down these heavily populated areas could mean keeping people closeted in very tight spaces, which could defeat the purpose of preventing transmission of the Delta variant.

Delta, which was previously known as Indian, was as contagious as chickenpox, according to the US CDC. To get a picture of how contagious Delta is, an individual with chickenpox is 90 percent likely to pass on the infection to people close to him or her who are not immune, CDC said.

Why resort to lockdown at all in places where you can’t keep people apart like in congested urban poor communities? According to Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Karl Kendrick Chua in a statement last year, the lockdown or enhanced community quarantine would avert an additional 323,262 COVID cases with 9,698 of these being severe or critical.

But lockdowns did happen and will happen soon. They have become part of the set of measures against COVID-19 worldwide.

NCR’s lockdown episodes would show numbers that may or may not lead to a conclusion over movement restriction’s effectivity as a measure to slow virus transmission.

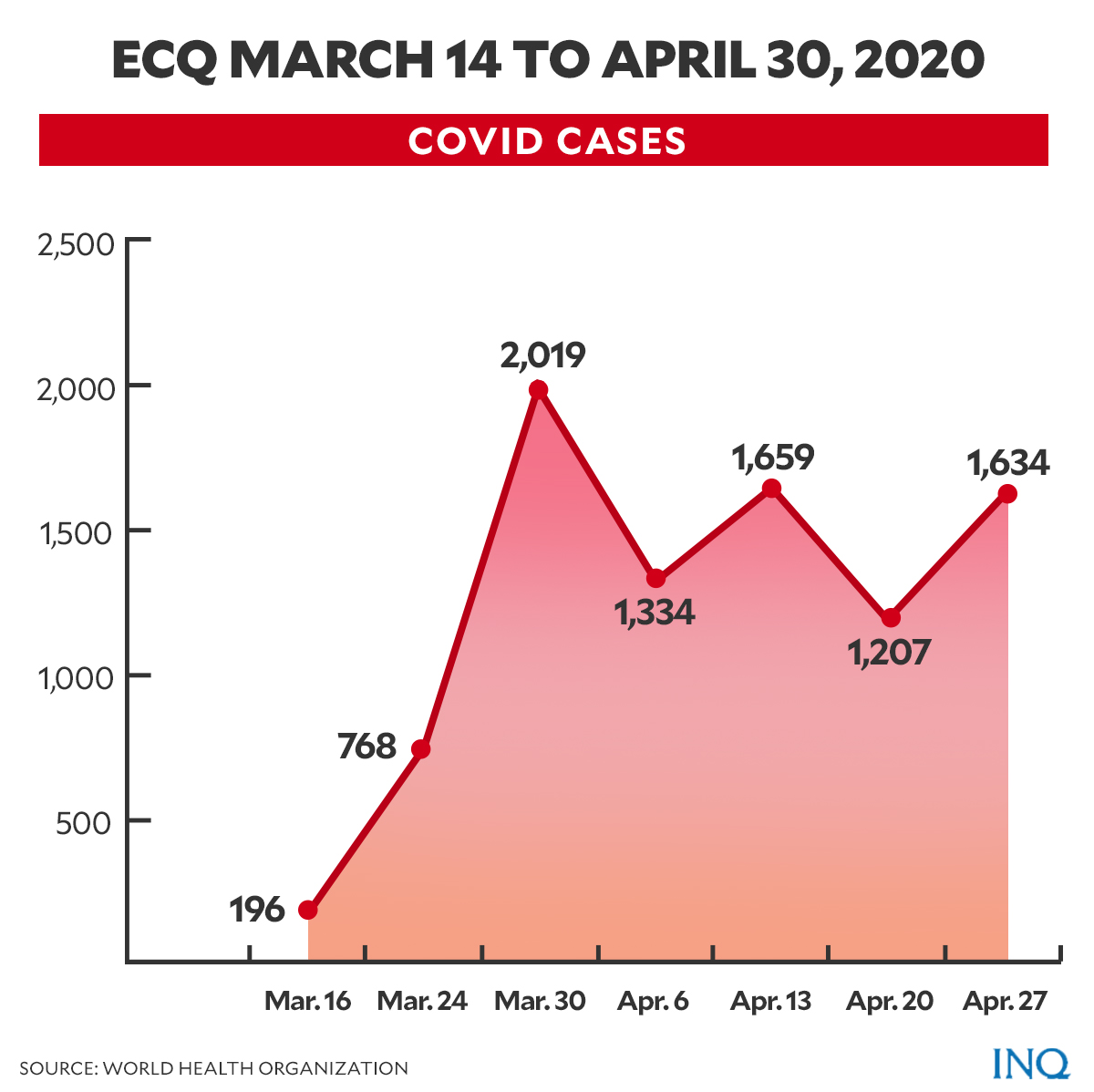

When the first lockdown, or enhanced community quarantine (ECQ), was imposed from March 14 to April 30, 2020, according to World Health Organization, there were 196 COVID cases on the second day of the lockdown, March 16. On March 23, there were 768 cases. On March 30, there were 2,019 cases. On April 6, or two days after the ECQ period lapsed, there were 1,334 cases.

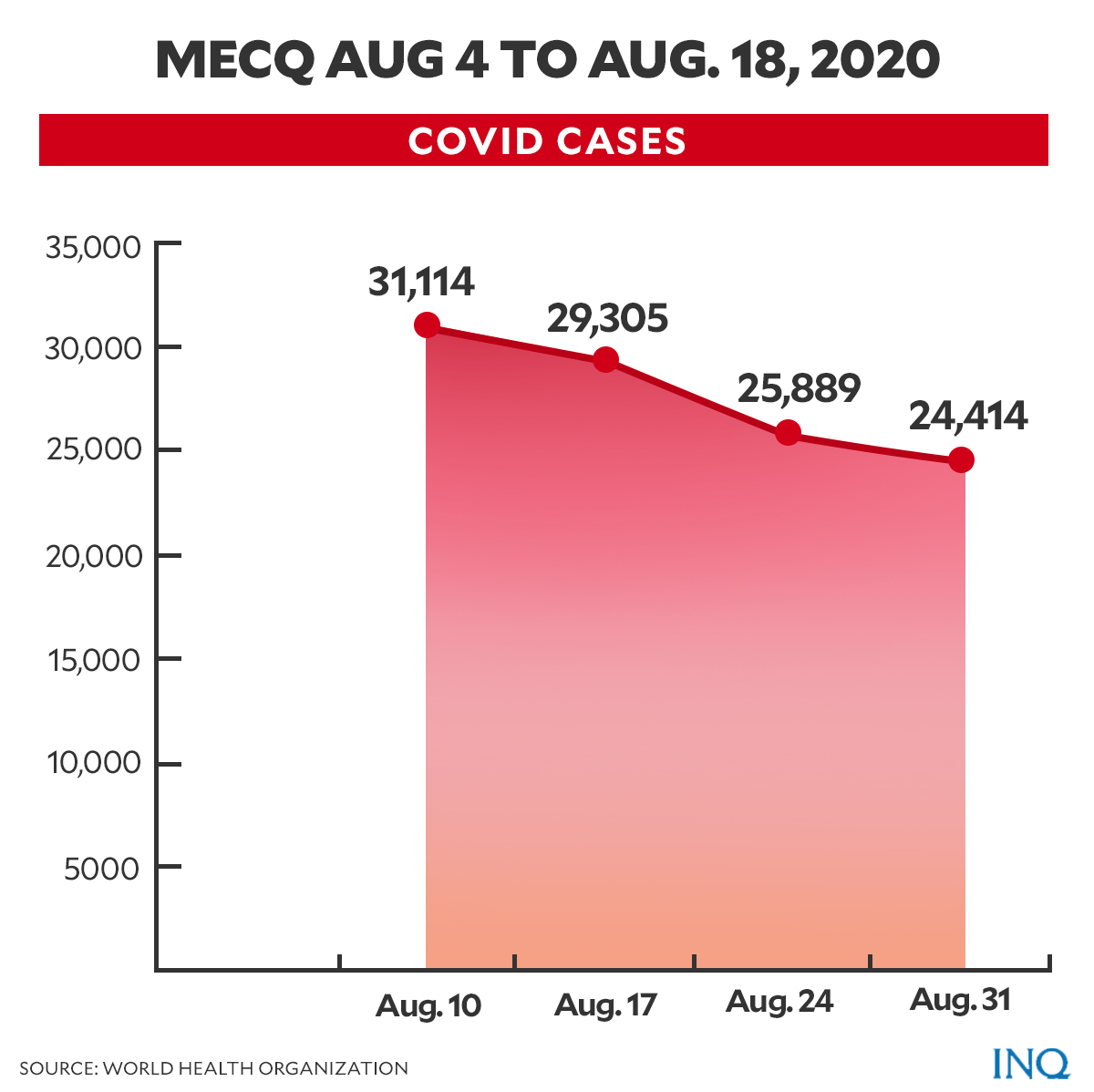

During the second lockdown, which transitioned to modified ECQ (MECQ) from Aug. 4 to Aug. 18, 2020, WHO said there were 2,463 COVID cases on Aug. 10, or six days after the start of the lockdown. On Aug. 17 or a day before MECQ lapsed, there were 29,305 cases.

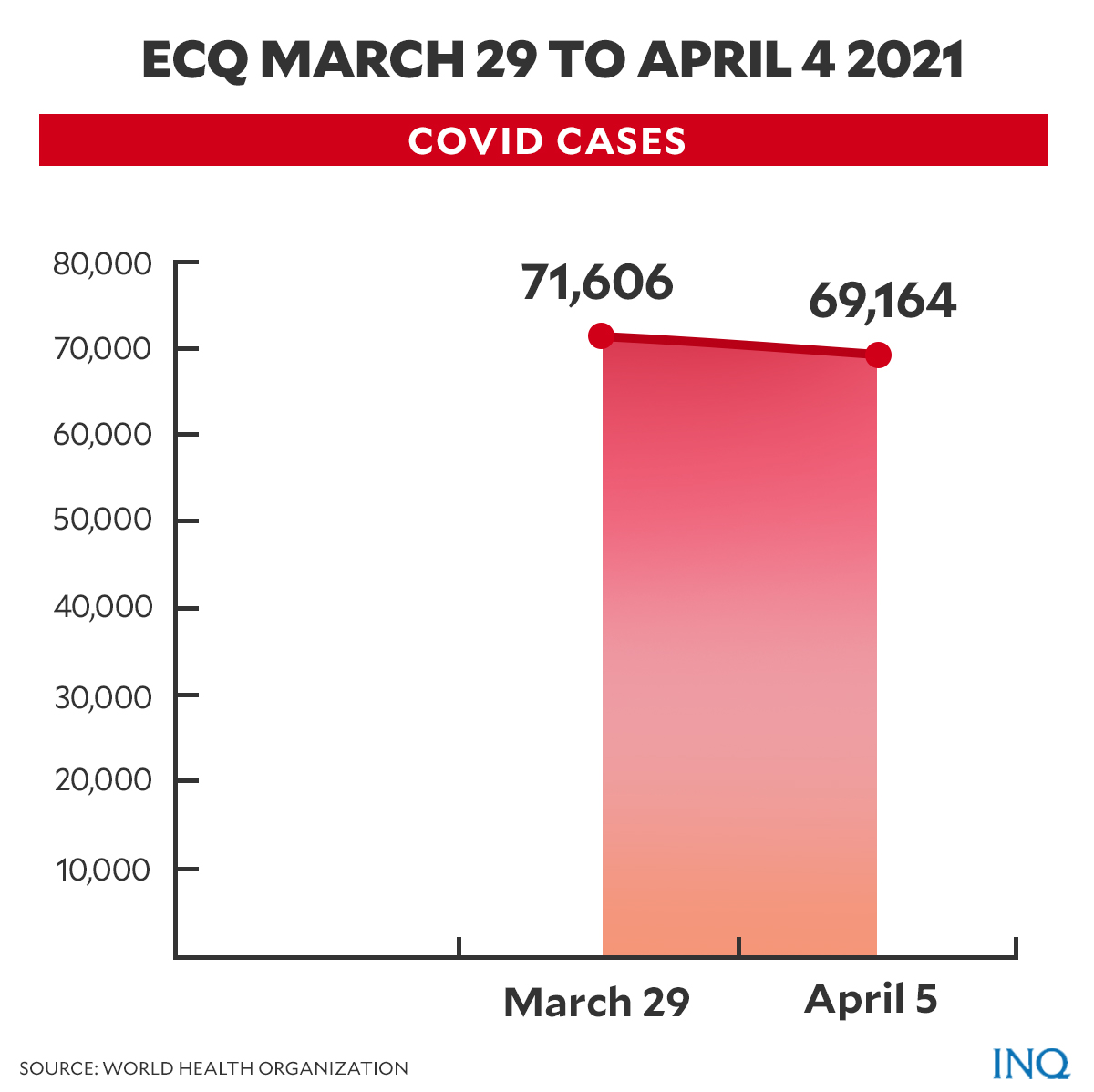

A third round of ECQ was implemented from March 29 to April 4, 2021. On the day ECQ took effect, there were 71,606 COVID cases, according to WHO. On April 5, the day after ECQ lapsed, there were 69,164 cases.

It’s not yet very clear how far the NCR lockdowns had been successful in achieving its main objective, to protect people from infections. But it came at a heavy price.

Unemployment in 2020 soared to 17.7 percent, or 7.3 million people, according to the April 2020 Labor Force Survey of the Philippine Statistics Authority.

In results of a survey done in November 2020, Social Weather Stations (SWS) said 48 percent of the Philippine population rated itself as poor. At least 12 million families rated themselves poor, according to the SWS polling. The striking number is that 2 million of these families are considered “newly poor.”

This coming ECQ starting on Aug. 6, millions of families are again facing an uncertain outcome. Duterte had asked the Department of Budget and Management to pin sources of funds for cash aid after repeatedly saying in the past that the government is running short of funds for the purpose.

The Department of Labor and Employment, quoted by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, projected the loss of more than 167,000 jobs.

Senate Minority Leader Franklin Drilon, and several other senators, are telling the government to stop the search for funds and simply look in the direction of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-Elcac), which in 2021 alone is getting more than P19 billion in funding.

The task force had already released billions of pesos to villages supposedly for development projects that would turn communities against communist rebels. An audit of the projects is being demanded although the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG), which downloaded the funds to villages, had provided a list of project descriptions.

Should funding be found, the government planned to distribute P1,000 in cash aid per individual and up to P4,000 per family during the two-week ECQ from Aug. 6 to Aug. 20.

It was, according to Bayan leader Renato Reyes, deceptive to give hope for aid but be unsure of the funding source.

In the meantime, people who have the money had formed long queues at grocery stores and supermarkets to load up on supplies. Malls, except for shops considered as essential, had turned dark again with restaurant after restaurant shut as early as Aug. 1.

Millions are hoping there’s light at the end of the seemingly endless tunnel.

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.