MANILA, Philippines — Let it now be known.

Former President Benigno “Noynoy” Aquino III narrowly survived a minor operation last year and firmly told his family and close friends not to disclose his failing health as he did not want people to think that he was just trying to get sympathy to evade possible arrest, according to his former Cabinet Secretary Jose Rene Almendras.

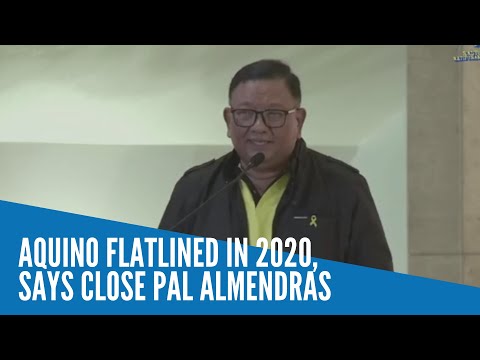

Almendras, one of Aquino’s bosom buddies, shared confidential information about his friend’s condition during the necrological rites for the former Chief Executive held on Friday night at Ateneo de Manila University, his alma mater.

“He was a fighter to the end. He’s not the type who will surrender,” Almendras told the crowd of about 100 people, including former Aquino Cabinet members, in the Church of the Gesu, where the urn containing the ashes of the former President was brought for public viewing.

Jose Rene Almendras INQUIRER PHOTO

Not while he’s alive

He said Aquino nearly died during an operation on his back in September 2020.

When he was given an anesthesia, the former President “flatlined for a few seconds,” Almendras said.

“We did not know what to do. Fortunately, the President was revived,” he said.

“I will say many things that I could not disclose before because P-Noy said, ‘You cannot tell that while I’m still alive,’” Almendras said.

“Mr. President, I admit that I violated your instruction,” he said. Almendras said he disclosed to Fr. Jose Ramon Villarin the former President’s condition the night before Aquino’s scheduled angiogram last month.

Villarin, the former president of the Jesuit-run university, has been a close friend of Aquino since college at Ateneo in the 1980s.

Broken heart

Talking about Aquino’s heart ailment during a Mass hours before the former Cabinet members’ gathering, Villarin said that after the angioplasty, Aquino told him that he had another type of “broken heart” which could not be healed.

Villarin believed that Aquino’s other heart problem was a result of disappointment with how things turned out after his term.

The Jesuit priest revealed that Aquino’s feelings and opinions about the Catholic Church and the justice system remained a secret between him and a few other friends, including Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, former Manila archbishop.

He said Aquino also lamented the country’s slow economic growth.

“This man carried the nation’s pains. The nation’s broken heart was the broken heart of this man,” Villarin said. “The nation’s broken heart was further assaulted by unbridled violence, the violence and fear that had been inflicted, and the cover-up of serious weaknesses.”

Almendras apologized to his former colleagues, their other friends and Aquino’s relatives for keeping his state of health a secret.

“Even his sisters could not share it because he told us, ‘Don’t tell anyone. This should be contained.’ It’s because he was a very private person,” Almendras said.

“He did not want to be accused that he just wants people to have pity on him … or that we were preparing just in case we will be jailed. That’s not true,” he said.

Aquino was facing charges in connection with the Dengvaxia fiasco in the Department of Justice and the deaths of 44 police commandos in Mamasapano, Maguindanao, in the Office of the Ombudsman. Both cases were dismissed for lack of merit.

Marcos ‘influence’

Almendras said Aquino wasn’t indifferent, detached, aloof and elitist as he was often accused of.

He said Aquino’s character as a person and views as a politician were largely influenced by his personal and family experience during the Marcos dictatorship.

Aquino is the only son of the martyred opposition leader, Sen. Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., and former President Corazon “Cory” Aquino, both democracy icons.

“Many say it’s difficult to understand P-Noy. I, myself, had a hard time understanding him at first. But if you read his father’s letter to him when (Ninoy) asked him to take care of their mother and his sisters, then you will understand him,” he said.

Almendras was referring to the letter that Ninoy wrote to his then 13-year-old son while he was incarcerated in a military cell at Fort Bonifacio on Aug. 25, 1973.

It read in part: “Forgive me for passing unto your young shoulders the great responsibility for our family … Son, the ball is now in your hands.”

He said Aquino once told him that they were like lepers as people kept away and did not want to be associated with the Aquinos.

Behind ‘wangwang’ policy

The abuse of power that he and his family had suffered under dictator Ferdinand Marcos prompted Aquino to impose the “no wangwang policy” after he took office, according to Almendras.

He said the blaring sirens from politicians’ cars to break through traffic, were the symbols of abuse of power that Aquino wanted to eradicate.

In his eulogy, former Interior Secretary Mar Roxas said his friend was a “selfless” leader.

Roxas, who gave up his presidential ambition in 2010 to be Aquino’s running mate, said being a stickler for the rules and his strong stance against corruption earned Aquino the ire of some politicians.

“But he persevered, trusting his values as his compass. Always, the national interest and the people’s welfare prevailed,” he said.

“Sir, it is my honor … to have been in the foxhole with you. Thank you very much for the opportunity to serve. Thank you for your leadership and your example. Thank you for the memories,” said Roxas, his voice breaking.