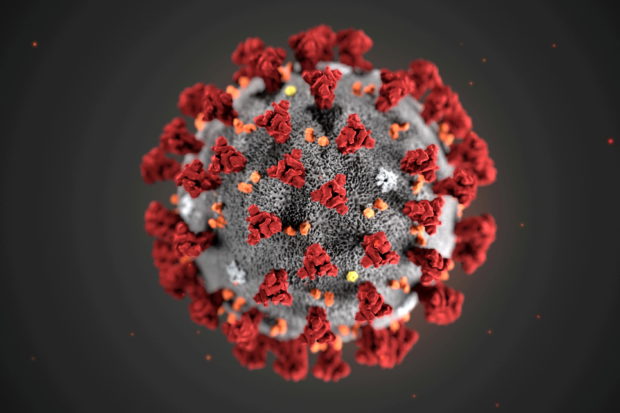

FILE PHOTO: The ultrastructural morphology exhibited by the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), which was identified as the cause of an outbreak of respiratory illness first detected in Wuhan, China, is seen in an illustration released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. January 29, 2020. Alissa Eckert, MS; Dan Higgins, MAM/CDC/Handout via REUTERS

Even mild cases of COVID-19 may lead to loss of brain tissue, according to findings from a long-term study involving 782 volunteers.

As part of the ongoing UK Biobank study, participants underwent brain scans before the pandemic.

For a before-and-after comparison, researchers invited 394 COVID-19 survivors to come back for follow-up scans as well as 388 healthy volunteers.

Most of the COVID-19 survivors had had only mild-to-moderate symptoms, or no symptoms at all, while 15 had been hospitalized.

Among the COVID-19 survivors, researchers saw “significant” loss of gray matter in regions of the brain related to smell and taste – the left parahippocampal gyrus, left orbitofrontal cortex and left insula.

Some of the affected brain regions are also involved in the memory of experiences that evoke emotional reactions, the researchers noted in a report posted on medRxiv on Tuesday ahead of peer review.

The changes were not seen in the group that had not been infected. The authors said more research is needed to determine whether COVID-19 survivors will have issues in the longer term with their ability to remember emotion-evoking events.

They also do not yet know whether the loss of gray matter is a result of the virus spreading into the brain, or some other effect of the illness.

Researchers hope to blocks cells’ response to the virus

Instead of targeting the coronavirus with experimental drugs, UK researchers are trying a new approach.

They are targeting infected cells to attempt to repair damage inflicted by the virus and prevent it from spreading.

To make copies of itself, or replicate, inside infected cells, the virus activates a cellular response called the “unfolded protein response,” explained Nerea Irigoyen of the University of Cambridge.

In laboratory experiments, the researchers inhibited activation of this cellular response using experimental drugs.

As a result, virus replication was prevented, according to a report published on Thursday in PLoS Pathogens.

The unfolded protein response in infected cells “might be responsible at least to some extent” for some of the complications associated with COVID-19, such as respiratory distress and thickening and scarring of lung tissues, Irigoyen said.

The approach must still be tested in animals and humans. But the research team is hoping that drugs that block the unfolded-protein response will not only reduce patients’ viral burden but also relieve some of the symptoms associated with the infection.

“This means that patients might have a better outcome and recover in less time,” Irigoyen said.