Dengue fever: Upstaged but not outmatched by COVID-19

This undated photo released by National Institute of Infectious Diseases via Kyodo News, shows a tiger mosquito. Dengue fever is transmitted by mosquitoes. (AP Photo/National Institute of Infectious Diseases via Kyodo News) JAPAN OUT

MANILA, Philippines—The COVID-19 pandemic has upstaged a perennial killer disease in the Philippines and other parts of the world—dengue fever.

Even as June is celebrated in the country as National Dengue Awareness Month.

Dengue has faded from national discussion since the COVID-19 pandemic struck in 2020, but the mosquito-borne disease continues to be a threat.

The war on dengue in the Philippines and elsewhere is far from over but battles have been won locally and internationally.

Fewer cases, infections

Department of Health (DOH) data showed that the number of dengue cases and deaths had been dropping since an outbreak in 2019 when the DOH declared a dengue epidemic after cases reached more than 400,000 with a death toll exceeding 1,000.

From Jan. 1 to Aug. 15, 2019, just a few days after a dengue epidemic was declared, the Philippines’ total dengue cases stood at 430,282 with 1,612 people dead.

BREAKING: DOH declares national dengue epidemic

During the same period in 2020, the DOH reported a total of 59,675 dengue cases and 231 deaths.

According to Dr. Norielyn Evangelista, program manager of the DOH’s Dengue Prevention and Control program, said the sharp decline in number of cases—76 percent—showed the effectiveness of the weapons used to fight the disease:

- Strengthened surveillance

- Case management and diagnosis

- Outbreak response

- Health awareness promotion

“We are now seeing the effects of the 4S strategy,” Evangelista said in 2020.

Heightened health awareness among Filipinos, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, was also being credited with a drop in dengue cases.

Recent numbers from World Health Organization (WHO) showed that from January to April 2021, there had been a total of 21,478 dengue cases in the Philippines with 89 deaths.

This was 56 percent lower than the 49,135 cases reported in the same period in 2020.

Mosquitoes’ poison

Dengue is not a communicable disease but is spread by virus-carrying female mosquitoes of the Aedes aegypti and Aedes altropicus breeds. Only female mosquitoes bite humans and spread the virus.

Scientists have found that mosquitoes transmit or acquire the virus from humans through their bites.

According to the DOH, the Aegypti mosquitoes are distinguishable by the white and black stripes on their tails.

The DOH also found that this type of mosquitoes keep a tight schedule in biting—from 6 to 8 in the morning and 4 to 8 in the afternoon and night.

These mosquitoes usually nest in clear water. Exposed containers or any object that can be filled with water when it rains can become a potential breeding site.

What are the symptoms?

According to the health department, some of the symptoms of dengue include:

- High fever that lasts between two to seven days

- Joint and muscle pain

- Weakness

- Skin rashes

- Stomach ache

- Nosebleed (once the fever starts to subside)

- Vomiting

- Dark stool

- Difficulty breathing

- Pain behind the eye

According to WHO, the critical phase usually starts around three to seven days after the disease sets in.

“It is at this time, when the fever is dropping (below 38°C) in the patient, that warning signs associated with severe dengue can manifest,” said WHO.

Severe dengue can lead to fatal complications due to blood plasma leaking, fluid accumulation, respiratory distress, severe bleeding, or organ impairment.

The warning signs include:

- Severe abdominal pain

- Persistent vomiting

- Rapid breathing

- Bleeding gums

- Fatigue

- Restlessness

- Blood in vomit

Patients experiencing these symptoms during the critical phase must be under close observation for the next 24 to 48 hours to avoid complications and death.

4 o’clock and the 4S

To curb the spread of the mosquito-borne disease, the DOH has been encouraging local government units (LGU) and the public to follow some preventive measures.

One of these was the 4 o’clock habit where communities are urged to search and destroy or overturn containers or areas which attract mosquitoes.

The health department reminded the public to always remember the 4S:

- Search and destroy mosquito breeding places.

- Self-protection.

- Seek early consultation.

- Support fogging or spraying in areas where there is a recorded increase in cases for two consecutive weeks to prevent an impending outbreak.

Scientific breakthrough

Science has made gains in the war on dengue and other diseases that mosquitoes carry, like malaria.

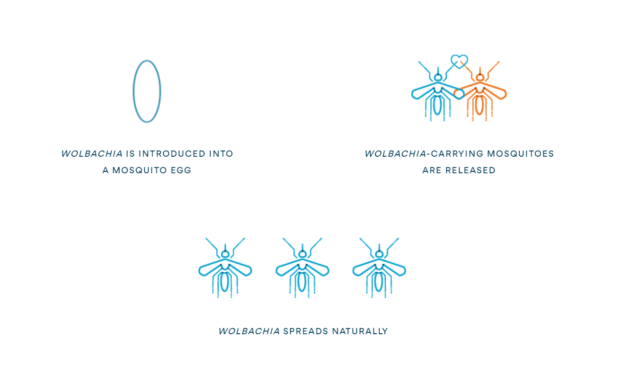

One of these is the World Mosquito Program (WMP), a non-profit initiative that aims to protect the global community from mosquito-borne viral diseases, by deploying a natural bacteria, called Wolbachia.

On its website, WMP said its scientists had discovered that Aedis aegypti mosquitoes carry Wolbachia, a bacteria which competes with viruses like dengue, zika, chikungunya, and the virus that causes yellow fever.

Wolbachia, WMP said, was found to make it difficult for viruses to reproduce inside mosquitoes. Mosquitoes carrying Wolbachia, WPS said, “are much less likely to spread viruses from person to person.”

Wolbachia is found in 60 percent of insects but is not normally carried by Aedis aegypti mosquitoes.

So scientists injected the bacteria into mosquito eggs. Once these hatches and send off grown mosquitoes, they are released to breed with local mosquito populations.

WMP said the method its scientists discovered was “natural and self-sustaining” compared to other techniques designed to prevent mosquito-borne diseases.

“Our method does not suppress mosquito populations or involve genetic modification (GM), as the genetic material of the mosquito is not altered,” WMP said.

The group has already released Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes in different communities across the globe. The first trials started in Australia.

‘Game changer’

WMP, along with the Gadjah Mada University, conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to measure the efficacy of deploying battalions of Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes in reducing dengue incidence.

The trial, which lasted from 2016 to July 2020, was done in Yogyakarta City in Indonesia with a total of 312,000 population.

According to WMP, the Wolbachia-carrying mosquitoes used in the study are from a mosquito colony that has been maintained in Yogyakarta since 2013.

Efficacy of Wolbachia-Infected Mosquito Deployments for the Control of Dengue

“Frequent outcrossing of the colony since 2013 with local wild-type mosquitoes ensures the genetic background of the mosquitoes is always well-matched to the mosquitoes flying around in Yogyakarta,” WMP said.

Trial results, published in The New England Journal of Medicine this month, revealed that:

- Incidence of dengue fell by 77 percent in Yogyakarta.

- Dengue hospitalization was reduced by 86 percent.

- Results carried implications for 40 percent of the world population at risk of dengue.

WMP also said in a statement that WHO’s Vector Control Advisory Group recognized the “public health value of Wolbachia against dengue.”

“I really think the results of this trial will be a game changer,” said WMP’s Director of Impact Assessment, Dr. Katie Anders.

“There have been a lot of people watching our work over the years – waiting to see the results of this trial. Now that they’re published people don’t need to take our word for it. The data is there that this really works to prevent dengue.” she added.

A more drastic tactic had also produced results in the war not only on dengue, but mosquitoes in general.

Another group of scientists resorted to editing the genes of mosquitoes so the insects would stop producing the variety that bites.

Last May, British-based biotech firm Oxitec and the Florida Keys Mosquito Control District (FKMCD) released their first batch of genetically modified mosquitoes.

Unlike WMP, Oxitec uses male mosquitoes which they said will pass on a gene that kills female offspring before they mature.

The altered gene will continue to be passed on as the male offspring mate with female mosquitoes.

Florida releases modified mosquitoes to reduce spread of disease

Economic impact

A study published in The Lancet, a peer-reviewed medical journal, found that the estimated global economic cost of dengue was US$8.9 billion per year.

The global economic burden of dengue: a systematic analysis

A separate review in 2020 said at least 40 percent of the economic loss was from reduced productivity as a result of dengue.

These were “the costs associated with productivity loss from both paid and unpaid work that results from illness, treatment or premature death.”

A 2018 research found that, in the Philippines, dengue has led to economic loss of US$139 million, or around P5.9 billion, and costs to patients and families of US$19 million, or P827 million.

Every year in the Philippines, dengue had been estimated to cost productivity loss of US$19 million or P821 million.

Estimating the Burden of Dengue in the Philippines Using a Dynamic Transmission Model

COVID-19 and dengue

As the Philippines battles with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, officials and the public are being reminded that other equally or more lethal diseases, like dengue, are just around the corner and waiting to strike especially during the typhoon season.

In an article published in the Western Pacific Surveillance and Response Journal (WPSAR) of WHO, Xerxes Seposo, assistant professor at Nagasaki University in Japan, said an increase in dengue cases in the Philippines is not remote, citing what happened in Singapore in 2020.

While most countries in the Western Pacific Region, including the Philippines, exhibited a decrease in dengue cases, Singapore has seen a “substantial increase in cases,” Seposo reported. He said it may “possibly associated with the country’s physical distancing measures implemented in response to COVID-19.”

“The rise in dengue cases in Singapore and the reduction in the Philippines and other countries in the region show how different control measures (e.g. mobility restrictions) can vary in their effects on levels of dengue,” he explained.

“The Philippines and other countries in the WHO Western Pacific Region did not see a similar increase in dengue cases in 2020,” the article said.

“However, caution should be exercised, because a trend of increasing dengue cases could still develop in current conditions,” Seposo added.

Several studies have also pointed to the difficulty in distinguishing dengue and COVID-19 symptoms as both share clinical and lab features.

In 2020, researchers found that at least 25 percent of patients with confirmed dengue have cough and at least 20 percent experienced upper respiratory symptoms—both of which are also COVID-19 symptoms.

In some cases, COVID-19 may manifest itself as fever with muscle and joint pains without respiratory symptoms, which are also present in patients with dengue fever.

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has released a chart showing the difference between dengue fever and COVID-19.

Co-infections have also been considered by some professionals, albeit the lack of available studies.

A case report published in WHO-WPSAR journal detailed the first reported dengue-COVID-19 co-infection in the Philippines.

It was a 62-year-old female, whose early symptom was fever and who was positive for SARS CoV2 and positive for dengue.

Dengue-COVID-19 co-infection: the first reported case in the Philippines

“The medical challenge of such co-infection lies in the similarity of the clinical and laboratory features of the two infections,” said Anyap Saipen, of the Department of Internal Medicine of the Baguio General Hospital and Medical Center.

“That is fever, myalgia and headache, associated with leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and abnormal liver function,” she said in a paper.

“Hence, it is important to consider the possibility of COVID-19 in patients positive for dengue and vice versa, since the result will affect management and prognosis,” she added.

TSB

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.