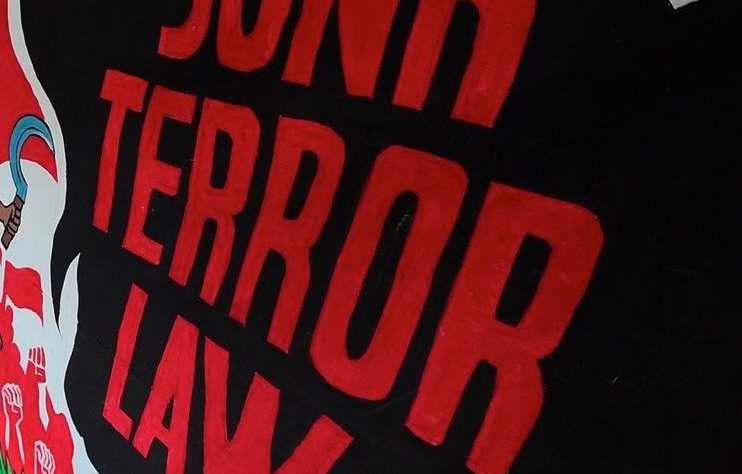

INQUIRER FILE PHOTO

MANILA, Philippines — Is rebellion now considered a terror act? Does adhering to communism and fundamentalist Islamism make one a terrorist? How does a person who has been declared terrorist by the Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC) contest the designation if it was done without due process?

These are just some of the questions that the Supreme Court had ordered the government to answer as it moved to conclude its scrutiny of Republic Act No. 11479, or the Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020.

In a notice to the parties, the high tribunal directed the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) and the 37 groups challenging the anti-terror law to sum up their respective positions by submitting their final memoranda within a non-extendible period of 30 days.

It reminded them that “no new issues” should be included in the documents and that the discussions should center on the six major topics that the court had already identified before it started the oral arguments.

As if asking them to answer an essay exam, the magistrates listed dozens of questions for government lawyers after the court opted to cancel the interpellation of National Security Adviser Hermogenes Esperon Jr., who Red-tagged several progressive groups when he spoke during the online court proceedings on May 12.

What is a terrorist act?

“Are all advocacies related to communism and fundamentalist Islamism considered by [Esperon] and ATC to be forms of terrorism?” read one of the justices’ questions.

“Is mere belief in the merits of a communist socioeconomic system or in fundamentalist interpretations of Islam considered a terrorist act?” they asked.

Define terrorism

They were also interested if Esperon would have the similar opinion on individuals “whose beliefs in capitalism or in Christianity may not be considered moderate.”

“How can the state assure that it will not come after dissidents or adherents of minority religious beliefs when membership by itself is a ground for prosecution under the [law]?” they added.

The 15-member tribunal asked the OSG to expound on the present state of terrorism in the country, the definition of terrorism under the new law, the role of the military in its implementation, and the authority of ATC in classifying groups and individuals as terrorists.

The OSG earlier admitted that the terror law did not specifically define actions that could be deemed as terrorist acts—a legal loophole—which the petitioners claimed would only lead to human rights abuses.

The high court likewise directed Esperon to back up his statement that the Philippines ranked 10th in the Global Terrorism Index and to explain if such classification “singled out” the effectiveness of an anti-terror law.

Moreover, it instructed the OSG to cite specific incidents that necessitated the repeal of the Human Security Act, which the magistrates described as “solely punitive.”