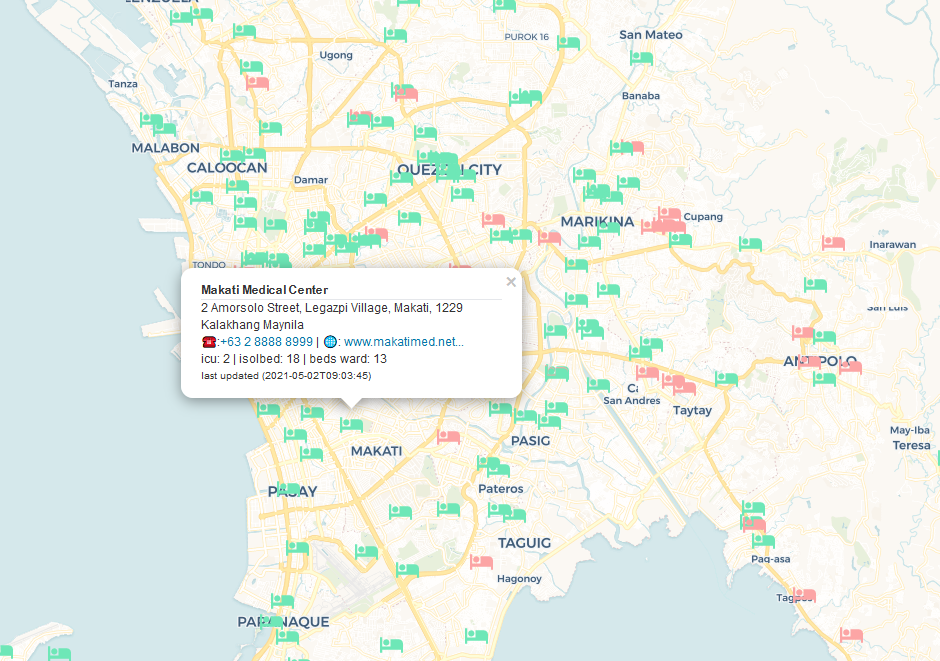

NO NEED FOR HOSPITAL HOPPING A “Cobeds19” screenshot

A new app developed by a Filipino data scientist could be a hope line for family members desperately seeking a hospital bed for their loved ones who are stricken with COVID-19.

However, the app, which uses figures from the Department of Health (DOH), is only as good as the government’s data, as one woman who was looking for a hospital for her cousin found out.

Mara Reyes, a graduate of the University of the Philippines who has a master’s degree in data science from the University of Sydney, created the “Cobeds19” app with her husband after she learned during the Holy Week that Filipinos had to “hospital hop” to get beds for sick relatives. That was when a new surge in cases started to overwhelm hospitals in Metro Manila and nearby provinces.

“We asked ourselves, ‘What could be a way for these people to know which hospitals have available beds?’” Reyes, who lives with her husband, Dax, in Australia, said in an email interview.

It was more a thought exercise at first, but over three weeks, the project evolved, she said.

She saw some infographics showing percentage of hospital vacancies, but there was no quick way to find their locations. She did find the information later—from the DOH daily data drops.

Working with her husband, Reyes wanted to develop a simple data visualization tool to answer the first question of where these hospitals are. “We thought the app might be more useful to others if it had details of the hospitals so that people can call and confirm first before they go. This would hopefully lessen having to go from one hospital to the other,” she said.

Real-world experience

The app, which opens with a map of the entire Philippines, shows hospitals with available beds in green, and fully occupied hospitals in red. (For color blind individuals, hospitals with available beds are blue and those at-capacity are dark red).But a real-world experience showed that the information might not be as up to date as users and the app developers would like them to be.

April Pacifico, a businesswoman from Makati City, tried to use the app in case her cousin, who was positive for COVID-19, needed to be hospitalized.

“I called several hospitals that were green on the app, but unfortunately they all said they had no vacancies, and there was a long wait list for most of them,” she said.

The app indicated that De La Salle University Medical Center in Dasmariñas, Cavite, had three available ICU beds and 22 isolation beds as of Thursday. But Pacifico was told on the phone that there were no vacancies.

Reyes admitted that the accuracy of the app’s data depended on information from the health department.

The time difference between Manila and Sydney, which is a few hours ahead, was also a factor.

“DOH mostly updates the file in the evening, but I am only able to download it the next morning to feed it to our app,” she said.

By the time users open the app, the information may be two days old, she said.

“For now, I can only make use of data that is available to us. Aside from that, not all hospitals update on a daily basis. I’m not sure if DOH can compel hospitals to provide them timely info, but I’m guessing our front-liners in the hospitals also have their hands full,” Reyes said.

The DOH says its data drop, which it calls DOH Data Collect, is updated daily and that “hospitals are compliant since April 2020.”

Pacifico also said some of the hospitals’ contact information were outdated.

Reyes said she and her codevelopers relied on their own searches on Google to input addresses and phone numbers of the nearly 1,300 hospitals in the database—a painstaking effort—because the DOH didn’t have them.

She welcomed any feedback that could improve the app and had already added a “contributed data feature.”

“Hopefully, it’ll be more helpful now,” she said.

Pacifico said that although she was unable to secure a bed for her cousin, she was thankful that many hospitals in the Philippines could be reached by phone with one easy-to-use app, which could accessed at: https://datascience.group/cobeds19.