Lapulapu: Hero behind the myth

BATTLE SCENE LANDMARK The Lapulapu Memorial Shrine and Museum, as shown in this artist’s perspective, will soon rise on the area where Lapulapu and his warriors defeated Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and his men in 1521. —PHOTO COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL QUINCENTENNIAL COMMITTEE

CEBU CITY, Cebu, Philippines — He is widely celebrated as the first Filipino hero.

But apart from successfully warding off Spanish invaders 500 years ago, very little is reliably known about Lapulapu.

“Nobody knows what happened to him [before and after the Battle of Mactan],” said Cebuano archaeologist Jose Eleazar Bersales, who studies human history through the excavation of sites and the analysis of artifacts and other physical remains.

The only existing primary source that mentioned Lapulapu by name was the account of Italian nobleman Antonio Pigafetta, the chronicler of the Spanish expedition led by Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan in 1521.

But Pigafetta’s accounts did not include details about the chieftain of Mactan Island.

The absence of a written account about the country’s first hero has given rise to myths and tales about the warrior.

One says the chieftain did not die or, at least, nobody saw him die.

Island ‘guardian’

Bersales said some islanders believed that Lapulapu did not die but turned into stone, which had been guarding the waters off Mactan.

Fishermen on the island would throw coins at the stone, which is shaped like a man, as a way of asking permission to fish in the chieftain’s territory.

Another tale revolved around how the warrior would know about the outcome of future battles.

His father, Datu Mangal, asked Lapulapu to make an “alho,” or pestle, out of a biyanti tree and throw it hard against a coconut tree.

If the pestle pierced the trunk, then he would emerge victorious against his enemies.

When Lapulapu threw the pestle, it did not only pierce a coconut trunk but it went through four others.

When the locality was still called Opon town in 1933, the local government put up a life-sized statue of Lapulapu armed with a bow and arrow, aiming at the old municipal hall.

Since then, Bersales said three mayors of Opon died in office, one after the other, due to heart attack. They were Mayors Rito dela Serna, Gregorio dela Serna and Simeon Amodia.

Superstitious Oponganons blamed the statue of Lapulapu for the officials deaths in succession.

BRAVERY This file photo shows a reenactment of the display of Filipino bravery and heroism as warriors led by Lapulapu repulsed Ferdinand Magellan and his European contingent in the Battle of Mactan 500 years ago. —CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

When Mariano Dimataga assumed the mayoral seat in 1938, the bow and arrow in the statue were replaced with a bolo.

Dimataga became the longest serving mayor—30 years as Opon mayor and the first city mayor when Lapu-Lapu was converted into a city.

While Lapulapu was known to be the leader of the group of men who emerged victorious in what is now called as the Battle of Mactan, writers and historians still debated whether he was the one who actually killed Magellan.

According to Danilo Gerona, author of “Ferdinand Magellan: The Armada de Maluco and the European Discovery of the Philippines,” a number of accounts have slight varying details on Magellan’s death but all of them seem to agree on one thing: Lapulapu did not kill Magellan.

Alex Manlapao, a professor of philosophy, ethics, humanities and the contemporary world at Colegio San Agustin-Bacolod, said various testimonies of chroniclers and eyewitness accounts described Lapulapu to be in his 70s who probably watched the battle unfold from a safe distance.

Magellan, on the other hand, was in his prime—an armor-clad warrior in his 30s or 40s, said Manlapao.

Pigafetta’s account, in the 1969 book, “Magellan’s Voyage: A Narrative Account of the First Circumnavigation,” said warriors of Mactan rained arrows, iron-tipped bamboo lances and stones on Magellan and his men, aiming at their legs since only their heads and bodies were protected with metal helmets and breastplates.

Pigafetta wrote that Magellan had only 50 soldiers during the battle against Lapulapu’s 1,500 warriors.

Cannons on the Spanish ships were rendered useless in the battle because these were out of range.

Magellan, who was hit by a poisoned arrow in the leg, ordered a retreat. A bamboo lance flew and wounded him in the arm, making it difficult for Magellan to draw his sword from its scabbard. Then a large javelin was thrust into his left leg, making him fall face down in the water, according to Pigafetta.

“On this, all at once rushed upon him with lances of iron and of bamboo and with these javelins, so that they slew our mirror, our light, our comfort, and our true guide,” he said.

After Magellan died, the remaining soldiers rushed back to the ship and fled.

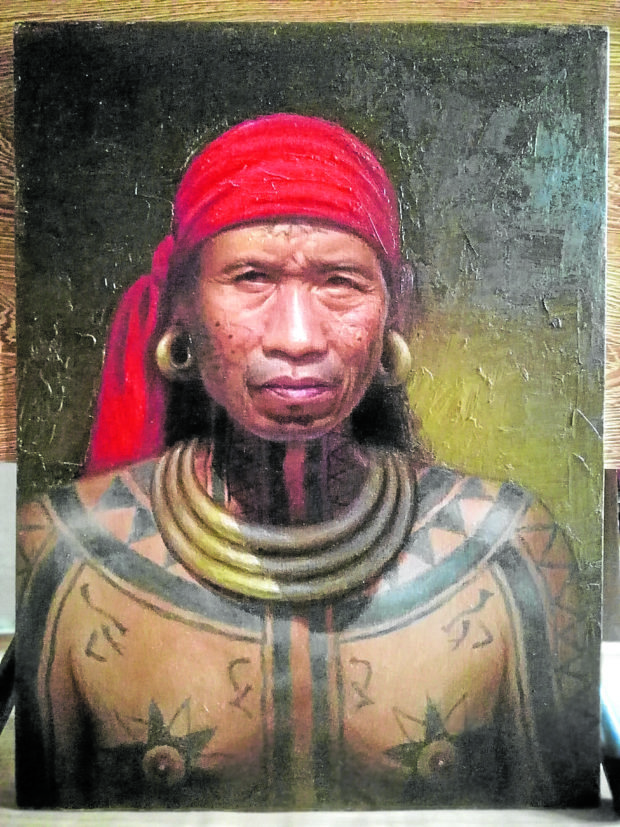

MACTAN CHIEFTAIN The 20-meter statue of Mactan chieftain Lapulapu will be transferred to the proposed museum that will be built in his honor in Lapu- Lapu City. Inset at top right shows Cebuano artist Ariel Caratao’s rendition of Lapulapu. —CONTRIBUTED PHOTOS

The outcome of the battle led to the departure of the Spaniards from the archipelago and delayed the colonization of the Philippines by 44 years until the conquest of Miguel Lopez de Legazpi in 1565.

By the time Legazpi arrived in Cebu, Bersales said there were no accounts as to what happened to Lapulapu.

“There were folklores that he went [to the neighboring] island of Leyte for fear of retaliation from the Spaniards. [It was also possible] that Lapulapu was already dead when Legazpi arrived [in Cebu],” said Bersales, also the director of the University of San Carlos Museum.

“Lapulapu is a model of bravery, courage, loyalty, and defending our territory against outside attack. He is a valid hero even at present,” Bersales said.

Victory site

The site of the Battle of Mactan—which lies on the boundaries of Barangays Punta Engaño and Mactan in Lapu-Lapu City—has been transformed into a monument and has become the venue of the annual “Kadaugan sa Mactan” (Victory of Mactan) celebration.

But for the battle’s quincentennial anniversary on April 27, the national government, through the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP), has decided to transform the Lapulapu monument into a shrine.

The new Liberty Shrine will showcase statues of Lapulapu and his men represented by at least five native warriors.

“It was never mentioned that it was Lapulapu who personally delivered the blow that killed Magellan. He fell down and was hacked to death. It was a collective effort,” said Rene Escalante, NHCP chair, in an earlier interview.

Adjacent to the shrine will rise the Lapulapu Memorial Shrine and Museum, which will break ground on April 27.

According to Escalante, the shrine’s roof will be shaped like a “sakayan” (boat), which “symbolizes our common maritime heritage.”

The 20-meter iconic statue of the chieftain that holds a sword in one hand and a shield in the other will be transferred to the museum’s atrium from its present location in the monument.

Both sides of the building will house galleries and function rooms while the middle portion will be a wide hallway.

The front portion of the shrine is a stage while the backside is a view deck of the sea, the mangroves and a recreational area.

Because it is boat-inspired, the structure will be constructed at a portion of the Mactan shore, about 200 m away from the existing shrine.

The project will not entail reclamation as it will be built on stilts, just a few meters from the shore.

According to Escalante, the shrine will give the country’s first heroes the proper recognition they deserve.

“Lapulapu [and the natives], not Magellan, will be the hero of the Philippine commemorative events. We want to reflect Filipino perspectives to celebrate our ancestors and not colonialism,” he said. INQ