DOST wood library digitizes its rare, valuable collection

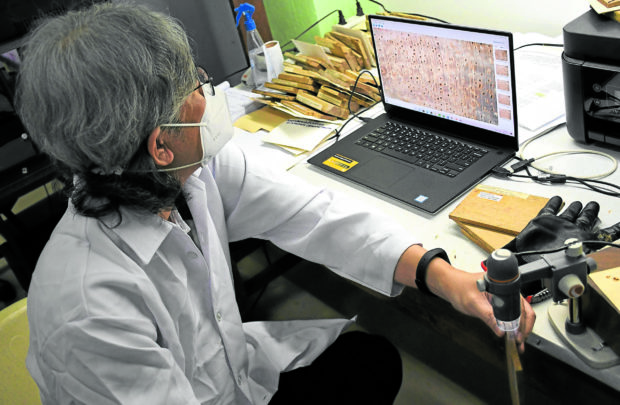

ONE OF ITS KIND Currently under the care of forester Glenn Estudillo, the Department of Science and Technology’s herbarium and xylarium—a depository of 16,348 local specimens and 5,274 foreign wood samples from more than 100 countries—are useful not only to students and researchers but also to the government’s campaign against illegal logging. Work is under way to create digital records of the samples, some of which date back to when the country was still under American colonial rule. —PHOTO FROMDOST-FPRDI

MANILA, Philippines – The Department of Science and Technology-Forest Products Research and Development Institute (DOST-FPRDI) is working to preserve its herbarium and xylarium (wood library) through digitization.

The process involves the inventory of the wood samples and capturing high-resolution (20x magnification) images of each using a digital microscope. The information and photos are uploaded into the database, and a QR code is assigned to each specimen for indexing and easier access.

The wood library, based in Los Baños, Laguna, and the only one of its kind in the country, hosts 16,348 local specimens and 5,274 foreign wood samples from more than 100 countries.

“This is a very rare and valuable collection since some of the collected species no longer exist in the natural forests,” said forester Glenn Estudillo of the DOST-FPRDI’s Material Science Division-Anatomy and Forest Botany Section. “We have to protect them because it will be hard to stockpile and impossible to replicate this collection again.”

Estudillo said the DOST-FPRDI was completing the digitization process and applying for a copyright of the images, and would open the digital wood library “soon.”Anti-illegal logging drive

Article continues after this advertisementThe wood library is not only a repository of knowledge for students and researchers but also a vital part of the government’s campaign against illegal logging.

Article continues after this advertisementIt provides evidence for cases filed against loggers and shipowners who transport illegally cut timber, and is used to determine whether wood seized by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources at ports and lumberyards came from natural and residual forests.

The DOST-FPRDI’s wood anatomists also serve as expert witnesses in court hearings.

Executive Order No. 23, signed in 2011, strictly prohibits the harvesting of trees in natural and second-growth forests. Only trees grown in industrial plantations can be cut down.

The wood library’s oldest sample dates back to 1903—a wood block from Shorea falciferoides locally known as yakal yamban and collected from Tayabas, Quezon, by one W.H. Wade.S. falciferoides has been tagged as “critically endangered” since 1998, and is on the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species.

This means that yakal yamban, which can be found only in the Philippines and Borneo, is in extremely high risk of being extinct in the wild due to excessive logging and wood harvesting.After the American Occupation in the early 1900s, US experts left their collection of wood specimens gathered from their exploration of Philippine forests to the then Bureau of Forestry.

During World War II, the collection was transferred to the Philippine Forest School, now the College of Forestry and Natural Resources of the University of the Philippines in Los Baños. It was eventually turned over to the DOST-FPRDI.

Chipped away

Estudillo said there was an urgent need to digitize the wood samples as these were being literally chipped away in time.

“Every time we identify a piece of wood, we cut a thin portion off the sample. Doing this repeatedly eventually shrinks the samples,” he said. “Digitization will allow us to identify the wood species while preserving the wood blocks.”

And digitization also allows greater accessibility to the wood library, Estudillo said.

A quick scan of a wood specimen’s QR code using a smartphone will generate information, such as its scientific, local and family names, voucher number, place of origin, name of the person who collected it and date of sampling.

“With the aid of highly magnified photos, one can identify the species faster and more accurately than simply using the naked eye and a hand lens,” Estudillo said.

Understanding the past

Wood identification helps archaeologists understand how our ancestors lived by identifying wood specimens recovered from their sites.

In 2017, the DOST-FPRDI researchers identified the tree species used in the structure, furniture and religious items in 15 heritage churches in Bohol and Cebu that were struck by the 7.2-magnitude earthquake in October 2013. The information helped the National Historical Commission of the Philippines in the restoration of the damaged buildings and artifacts.

Wood identification is also helpful to clients in the construction, furniture and handicraft sectors who need assurance on the sources of their wood materials.

The DOST-FPRDI’s herbarium and xylarium stores wood specimens of varying shapes and sizes—from the standard 6-inch-long, 3-inch-wide and 0.5-inch-thick slabs, which are around the size of the large-screen “phablets” (portmanteau of phone and tablet), up to samples the size of a tree stump.

Samples of common woods are on shelves at the air-conditioned library office. Rare specimens used as references in the wood identifying service are stored in folders in multilevel cabinets.