Splitting Palawan into three provinces would adversely impact its unique biodiversity and already threatened wildlife, conservationists warned on Tuesday, as the clock ticks nearer the scheduled plebiscite for the island’s proposed division.

The division, they said, would not only open Palawan’s extensive natural resources to potential mismanagement but would allow extractive and destructive industries, such as large-scale mining and plantations, to take root and destroy the rich ecosystems that gave the province its reputation as the country’s “last ecological frontier.”

Environmentalists and members of the One Palawan Movement scored the alleged lack of studies and consultation on the proposed split under Republic Act No. 11259, which was signed by President Duterte in April 2019.

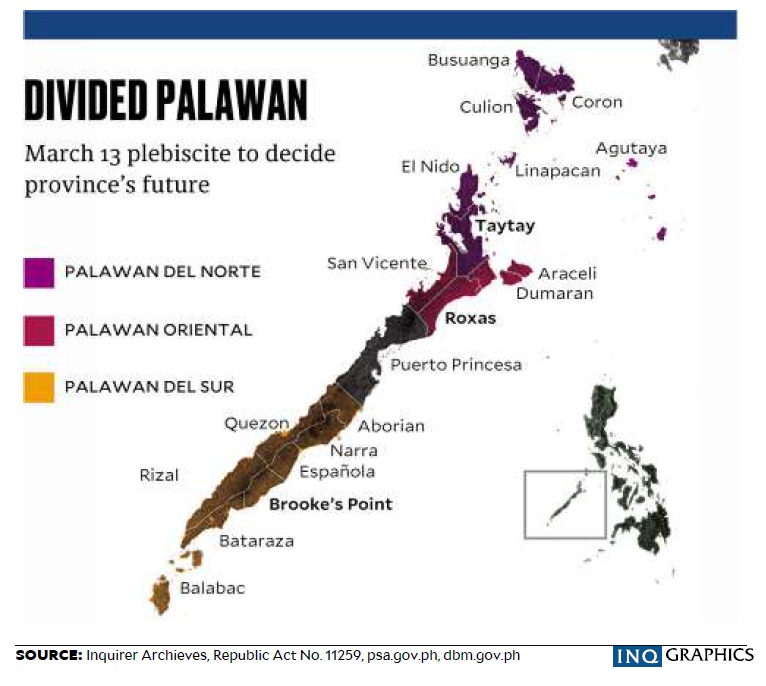

A plebiscite will be held on March 13 to ratify the law dividing Palawan into Palawan del Norte, Palawan del Sur and Palawan Oriental. Voters in the capital Puerto Princesa City will not take part because the law states that it will have its own district representative.

The campaign period for the plebiscite starts on Thursday.

Exploitation, wildlife crime

The forests of Palawan, the largest province in the country in terms of total area of jurisdiction, are home to more than 400 species, several of which are endemic to the Philippines. With more than 5,600 hectares of mangroves, it hosts at least 22 percent of the country’s mangrove cover and leads provinces in fisheries production.

This rich biodiversity is already under threat of exploitation, unabated land conversion and wildlife crime, but the situation may worsen should Palawan be split, said Aldrin Mallari, president of Center for Conservation Innovations.

“Our action—or lack thereof—has been dividing Palawan into three or more parts already,” he said in an online forum on Tuesday. “Dividing Palawan into three provinces will be the last nail in the coffin.”

Splitting Palawan takes away from the central priority of local officials and communities, which is to conserve what is left of the province’s wildlife and their habitats, conservationists said.

Mallari said the province had been losing 13,323 hectares of forest cover a year. If the trend continues, it may be left only with forests on mountaintops in 30 years and along with that, the extinction of more than half of its unique biodiversity, he said.

“When you divide governance or jurisdiction, you cannot set aside the possibility that some provinces may be better performing than others [in terms of resource management and conservation],” Mallari said. “But ecosystems do not look at political boundaries.”

Grizelda Mayo-Anda, executive director of the Puerto Princesa-based Environmental Legal Assistance Center, challenged the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) and the local officials forming the council to “study first the impact of the proposed division.” PCSD is a unique interdisciplinary body that is tasked with overseeing and implementing the strategic environmental plan for the province alone, which has eight protected areas and several key biodiversity areas.

Instead of dividing the province, the government should focus on empowering local governments to strongly implement wildlife laws and manage their natural resources, Mallari said.

“We need to strengthen the local government, down to the municipal and barangay levels,” he said. “We also need science-driven management where our actions are not driven by political reasons, but by what the science tells us.”

Growth

Civil society groups opposing the split said creating more provinces would not necessarily mean growth for Palawan.

Ferdie Blanco of the One Palawan Movement said “laggard” provinces, or those created from political subdivisions, had been reporting higher poverty incidence, citing an unpublished study in provinces in the Davao region.

“In every divided province, there is a laggard province. Even though the internal revenue allotment (IRA) increased, it will not be felt by all,” Blanco said.

But Winston Arzaga, provincial information officer, disputed Blanco’s claim, saying the equal IRA-sharing of the three provinces would help boost the local economy as it would promote new businesses and opportunities.

He said the total IRA of Palawan would increase from 10 percent to 13 percent if the province would be split.

Arzaga said the provincial government’s information and education campaign (IEC) since 2019 had reached all towns and succeeded in explaining the benefits of the split to residents.

“We in provincial government do not stop conducting the IEC. ‘Yong mga tao, mas naliliwanagan na maganda ito para sa atin (The people are becoming more enlightened that this is beneficial for us),” Arzaga said. —WITH A REPORT FROM ROMAR MIRANDA