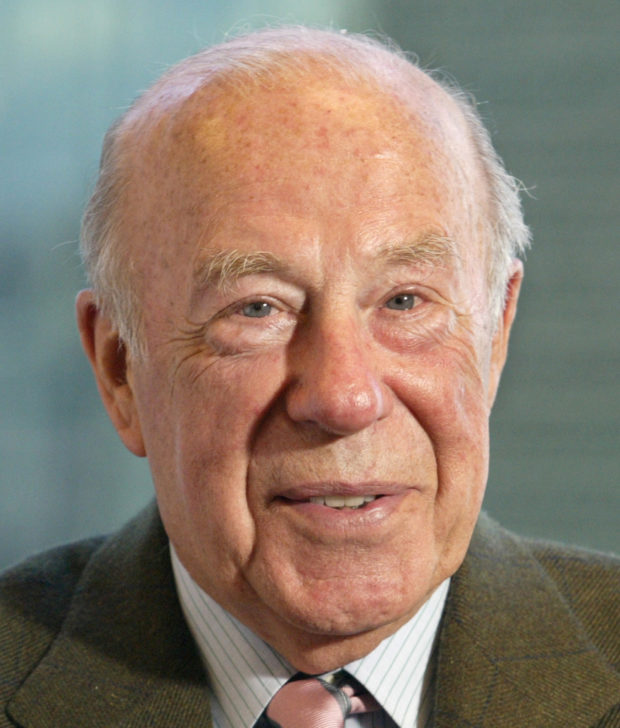

FILE PHOTO: Former U.S. Secretary of State George P. Shultz talks during an interview in San Francisco, April 17, 2003. REUTERS/Lou Dematteis/File Photo

WASHINGTON – George Shultz, the U.S. secretary of state who survived bitter infighting in President Ronald Reagan’s administration to help forge a new era in American-Soviet relations and bring on the end of the Cold War, died on Saturday at age 100, the California-based Hoover Institute said.

A man of broad experience and talents, Shultz achieved success in statesmanship, business and academia. Lawmakers praised him for opposing as sheer folly the sale of arms to Iran that were the cornerstone of the Iran-Contra scandal that marred Reagan’s second term in office.

His efforts as America’s top diplomat from 1982 to 1989 under the Republican Reagan helped lead to the conclusion of the four-decade-long Cold War that began after World War Two, pitting the United States and its allies against the Soviet Union and the communist bloc and generating fears of a global nuclear conflict.

Shultz, a steady, patient and low-key man who became one of the longest-serving secretaries of state, steered to completion a historic treaty scrapping superpower medium-range nuclear missiles and set a pattern for dealings between Moscow and Washington that made human rights a routine agenda item.

He achieved the rare feat of holding four Cabinet posts, also serving as secretary of the Treasury, as secretary of labor and as director of the Office of Management and Budget.

His record as secretary of state was tempered by his failure to bring peace to the Middle East and Central America, areas in which he personally invested considerable effort.

Shultz remained active into his 90s through a position at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution think tank and various boards. He also wrote books and took stands against the Cuban embargo, climate change and Britain’s departure from the European Union.

His most recent book, written with James Timbie, a longtime State Department adviser and published in November 2020 ahead of Shultz’s 100th birthday, was entitled “A Hinge of History.” It suggested the world was at a pivot point not unlike the one it faced at the end of the second World War.

“We seem to be in an upset state of affairs where it’s hard to get things accomplished,” he told the New York Times, lamenting the Trump administration’s resistance to international accords. “They seem to be skeptical of these agreements, of any agreement. Agreements aren’t usually perfect. You don’t get everything you want. You compromise a little bit. But they’re way better than nothing.”

SERVED EISENHOWER, NIXON BEFORE REAGAN

Before joining the Reagan administration, the New York City native served in senior positions under Republican President Richard Nixon, who made him labor secretary (1969–70), the first director of the White House Office of Management and Budget (1970–72) and treasury secretary (1972–1974). He previously was on Republican President Dwight Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisers.

Shultz’s background was in economics. After leaving the Nixon administration in 1974, he went to Bechtel Corp, the international construction firm, eventually becoming its president. He stayed there until Reagan asked him to replace Alexander Haig, who resigned under pressure as secretary of state in 1982.

Shultz was unable to stop the arms-for-hostages deals with Iran that generated funds for the Contra rebels fighting against Nicaragua’s leftist government. He did help broker agreements that eased the disputes of Nicaragua’s civil war.

The arms sales to Iran came during an arms embargo on that country. The proceeds from the sales were secretly diverted to the Contra rebels at a time when Congress had banned such funding. National security adviser John Poindexter and aide Lieutenant Colonel Oliver North took the blame for the scheme.

Shultz told a 1987 congressional hearing that he was lied to repeatedly by the head of the CIA and Reagan’s national security advisers who withheld information from him and the president in order to keep the Iran arms sales going.

Shultz previously had advocated support for the U.S.-backed Contra rebels, known to Reagan’s team as “freedom fighters.”

Asked whether the United States had benefited from the Iran-Contra efforts to fund the rebels, Shultz bluntly told lawmakers, “I don’t think desirable ends justify means of lying, deceiving, of doing things that are outside our constitutional processes.”

He said he threatened to resign three times during the scandal. But, believing Reagan needed him, Shultz stayed to try to mend the damage to U.S. foreign policy. His price: reassertion of State Department power over foreign policy.

RIVALRY WITH WEINBERGER

Shultz steadily accumulated power, sometimes at the expense of Defense Secretary Caspar Weinberger, a Reagan confidant once seen as his chief administration rival.

He won control of policy in the Middle East, resulting in a diplomatic campaign to isolate Iran that led to a U.N. ceasefire order in the lengthy Iran-Iraq war. Shultz’s tough stance was adopted by Reagan when U.S. planes bombed targets in Libya in April 1986 over Weinberger’s opposition.

Weinberger won and Shultz lost when Reagan opted in 1986 not to be bound by the unratified 1979 SALT-2 arms control treaty.

In achieving the intermediate-range nuclear forces treaty in 1987 and helping forge new relations with the Kremlin, Shultz prevailed over hard-liners. The Cold War ended in 1989 after he had left office and the Soviet Union broke up in 1991.

Shultz had degrees from Princeton University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and taught at MIT and the University of Chicago. Following his State Department stint, Shultz became an economics professor at Stanford.

Born in New York on Dec. 13, 1920, the son of a historian, Shultz joined the Marine Corps in World War Two. He met Army nurse Helena O’Brien in the Pacific and they were married in 1946 and had three daughters and two sons.

A man of usually impassive demeanor, Shultz was an enigma to the public and intimates alike. Revealing moments were rare, such as when State Department colleagues bid him an emotional farewell on Jan. 19, 1989, at the end of Reagan’s presidency.

Visibly moved, he clutched the arm of his wife, who accompanied him on his many travels. “We came as a package deal and we leave as a package,” Shultz said.

Helena died in 1995 and Shultz married San Francisco socialite Charlotte Mailliard Swig in 1997.

He had a love of dancing, swimming, tennis and quirky clothes, such as a peach-colored sports coat and multicolored golf slacks.

His most tantalizing accouterment was said to be a tiger tattoo on his left buttock, a souvenir of his student days at Princeton University, whose mascot is a tiger. Shultz was coy about whether he really had one, but he did not deny it.