Fight against sexual abuse starts in family

SEEKING HELP Victims of sexual violence turn to Sagip Center in Muntinlupa City for support and protection against their attackers. Social worker Adelfa de Guzman says cases of incest are the most difficult to handle. —MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

(Last of three parts)

The COVID-19 pandemic caught everyone off guard. Cities and towns were locked down, people’s movements were limited, big and small businesses, even schools, were shuttered.

Help desks and shelters for victims of sexual violence were no exception.

In Muntinlupa City, a few months into the quarantine, police laid down a “no in, no out” policy in the custodial center for offenders. So when a case of father-child incest was reported, the father was “evicted” from the family home instead of being held at the police station, says social worker Adelfa de Guzman.

It was one of the interventions that the city’s Sagip Center came up with to ensure the safety of children and women during the pandemic.

Sagip Center, a 24/7 crisis center for abused women and children, is a nongovernmental organization (NGO) established in 1998. It was fully turned over to the local government of Muntinlupa in 2017.

To ensure easy reporting of abuse, its staff’s contact numbers were posted publicly and its personnel mobilized to serve in their communities and barangays, De Guzman says. But the pandemic and health measures, including COVID-19 testing, caused a slowdown in its operations, as well as in the admission of abuse victims.

Sagip Center not only provides shelter, psychosocial intervention, health and medical services, and overall support for abuse victims but also assists in the legal process.

The victims usually stay in the center for a month or until the staff has ensured their safety and found an alternative family, usually relatives, that would take them in. When they feel ready to return to their homes, “community partners” are available to see to their welfare.

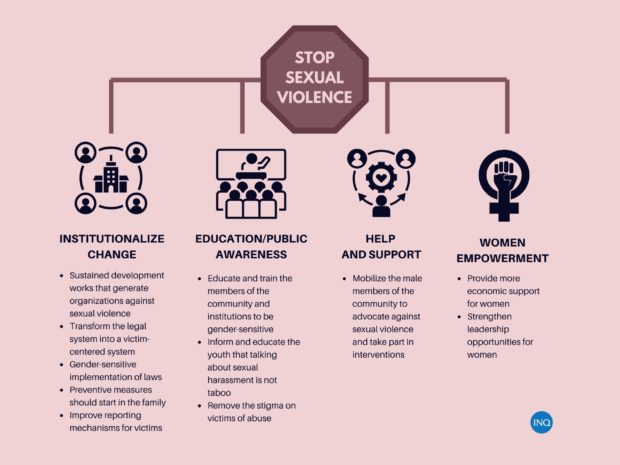

Among these community partners are the violence against women and children’s (VAWC) desks and watch groups. “It’s a collaborative effort in the community,” and includes male advocates, De Guzman says.

She says that in encouraging men to take part in the interventions to stop sexual violence in their community, the message is sent: “Protecting women and children from abuse is a responsibility not only of women or men, but of everyone.”

Bahay Kanlungan

The fight against sexual violence is likewise continuing in Quezon City, as shown in the recent opening of Bahay Kanlungan, the first shelter run by a local government for abused women, children and LGBTs.

Due to pandemic health measures, Mayor Joy Belmonte initiated the building of this temporary center in a government-owned space that can admit victims who need to be immediately removed from their homes.

“We have a social worker, admin and house parents in place, but we are still waiting for the [completion] of the dirty kitchen and washing area. Hopefully, by next year, the shelter can operate,” says Janet Oviedo, women’s unit head of the Office of the City Mayor.

The local government also has the 8-year-old Quezon City Protection Center, a one-stop shop that provides immediate interventions—medicolegal assistance, legal, police and psychological support—for victims of violence and sexual abuse.

What is avoided is subjecting the victims to the ordeal of having to repeatedly narrate their experience to those providing immediate intervention, Oviedo says. When that happens, “they tend to end up feeling more abused.”

In a hallway in City Hall, “Don’t Tell Me How to Dress,” a collection of clothes worn by victims of sexual violence, is displayed to raise public awareness that they should not be blamed for being assaulted.

A baby’s clothes displayed next to a schoolgirl’s uniform represent what a 4-month-old was wearing when she was found in a coconut field in Cebu in 2017. A cadet’s uniform, a pair of jeans and a white shirt, among other clothing, are also shown, with short narratives of rape, assault and molestation.

Oviedo underscores the importance of public awareness. She says the youth need to be provided information and education that being aware of sexual harassment is “not taboo.”

Quezon City also implements a mechanism where a point man takes charge of bringing gender and development programs to the barangay level. It is also a priority to connect victims to relevant women’s groups and NGOs.

But while local governments like Muntinlupa and Quezon City have resources and facilities to help victims of sexual violence, it’s a different case at the barangay level.

Private space

Small barangays that lack private space for those abused “compromise the identity of the victim-survivor and the confidentiality of the case,” says Ma. Aurora Lolita Lomibao, a communication research professor at the University of the Philippines whose postgraduate dissertation focused on front-line VAWC desk officers.

Her study’s preliminary findings showed that in many barangays, the desk officers had to share office space with health workers, “tanod” and other officials, who had to be shooed out when a case arose.

Lomibao notes that this contributes to the low reporting of abuse, with victims feeling ashamed of their experience and vulnerable to the resulting stigma.

Nevertheless, Lomibao cites the “zealous record-keeping” of the desk officers. “In fact, one desk officer frequently wished for a computer to make their record-keeping faster and more efficient,” she says, adding that of the 12 barangays covered by her study, only Ayala-Alabang had an electronic filing and reporting system.

VAWC desk officers “generally respond with compassion and empathy” when an abuse victim reaches out to the barangay, says Lomibao. Desk officers know how to immediately respond—for example, she says, when a woman has been physically injured by her husband, they provide first aid, shelter, and sometimes even clothing.

They undergo basic training with the Philippine National Police and the Department of the Interior and Local Government, and are informed of women’s rights and of the referral system and proper procedure in handling complaints, she says.

But they still hold deeply rooted gender beliefs, such as that “all individuals are heterosexual,” Lomibao notes. She says this belief ensures the “good parent” stereotype that is exclusively carried by the woman. Hence, she says, when a woman is beaten by her husband, desk officers tend to tell her, “Maybe you were a nagger. That’s why he hit you.”

In the family

While efforts and preventive measures at the city government and barangay levels are crucial in the battle to fight sexual violence, dealing with its root “should start in the family, [where] the cycle of abuse and violence [happens],” says Andrea Martinez, a psychology professor at the University of the Philippines.

Martinez cites a 7-year-old client who was assaulted by her elder brother. At a family picnic, the child suddenly recalled how it happened in the car and blurted out: “Kuya did this to me.” The parents, shocked, said: “What are you saying? That’s bad!”

As it turned out, Martinez says, the sexual violence was invalidated and the child appeared as the “bad” person instead of the brother who had wronged her. “That’s even more traumatizing than the rape itself because they are trying to get the sympathy of the people they expected to defend them, but didn’t,” she says.

Parents are the first responders and should be sensitive, especially toward the victim’s initial disclosure. When the abuse is done, “do we just let them be and think that they will eventually forget what happened?” Martinez says. “[No,] we have to help them process it so it won’t have a lasting effect on them.”

De Guzman, a social worker for 20 years, says that in cases of incest, “transforming” the mother into potential support for the child” is a crucial step, which entails determining why the abuse happened in the first place.

It takes at least two years to turn the family into a support system for the child, she says, adding: “If the abuse happened in the home, it is not only the direct victim that needs healing, but the whole family.”

But it’s a different matter for abused wives.

Says De Guzman: When a battered woman first steps into Sagip Center to report her abuse, her definition of justice is prosecution. Once her anger subsides, that definition becomes family preservation; she will withdraw the case, citing economic reasons, her children’s welfare, their family’s reputation.

“At the height of pain or anger, the woman tends to think of herself, but as it recedes, her welfare will be her last priority,” she says.

Empowerment

To effectively respond to sexual violence, preventive measures should start in the family, as Martinez says, and it should also be holistic—streamlined from the barangay to the local government, up to the various institutions (legal, psychological, medical and social welfare) that offer help to survivors of abuse.

In giving help, the aim is always to empower in a way that “when a woman sets foot in our office crying, we make sure that before she turns her back on us, we see a light on her face, meaning she knows what to do next,” De Guzman says.

But there is no linear process or a single measurement in the recovery process, she says. What’s important is the community’s support, until survivors of abuse “regain their power to talk and to trust again.”

For more news about the novel coronavirus click here.

What you need to know about Coronavirus.

For more information on COVID-19, call the DOH Hotline: (02) 86517800 local 1149/1150.

The Inquirer Foundation supports our healthcare frontliners and is still accepting cash donations to be deposited at Banco de Oro (BDO) current account #007960018860 or donate through PayMaya using this link.