(Second of three parts)

“I kept questioning the validity of my story,” says “Ana” as she narrates how she was assaulted last year.

During an evening party at a conference held abroad, a man approached Ana and began hitting on her. “He was touching me without my permission, but I was in a good mood at that time so I thought it was just fine,” she says.

They eventually agreed to have sex, and proceeded to her hotel room. Ana insisted on the use of a condom, but he kept “pushing even though I said no.”

He managed to penetrate her without protection, and at that moment, Ana says, her brain shut off. “I remember thinking, ‘Why am I not saying no right now?’”

After the conference, the guy immediately blocked Ana on social media, which made her think that perhaps “he was regretting [what] we had in the event.”

It took her nine months to realize that what happened was an assault: “I had wanted to say no but I didn’t, and he just kept going even though I said no earlier on.”

The realization came after she watched Butch Dacanay’s “Jenny Li,” an online play that addresses the issue of rape and the courage it entails for victims to come forward, Ana says. But she “felt nothing” about the assault as she had begun to doubt that it was rape.

It was only at the height of #HijaAko—a social media movement on Twitter aiming to push back against rape culture in the country—and upon reading posts of her friends’ own stories of sexual abuse did it hit her: “That was what it was.”

She knew the difficulty of seeking legal action against her attacker. As a last resort, she posted her story on Twitter using #HijaAko.

The feedback was instantaneous, Ana recalls: “My phone kept buzzing. People were messaging me, asking if I’m OK. Some even reached out and told me the same thing happened to them.’’

“At first it felt heavy,’’ she says. “But then the mental load was eased because of sharing that story and knowing that other people carry the same mental load, that there is support from my friends. It helped me.”

She managed to undergo psychological therapy to process what happened, but remained “paranoid” and reluctant to tell her family about the incident. “It is not a conversation I want to have [with them].”

For Ash Presto, a sociology instructor at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman, social media is helpful in creating a community of women supporting women.

But for Malou Alcid, professor of social work in the same university, social media may prove fast and effective in launching campaigns and awareness, but it caters to a particular audience: the youth and the middle- to upper-class.

“It cannot reach older generations because they are usually not on social media,” she points out.

Sustained development work

Alcid thinks it’s a challenge for movements such as #HijaAko to be sustainable and provide a deeper understanding of a problem because appreciation for the issue will be limited to one-liners or a certain number of Twitter characters.

What is still needed, she believes, is sustained development work that generates organizations that can “institutionalize the issue.”

But Ana, who “grew up not trusting the systems” that are supposed to help vulnerable sectors, and who studied in a girls-only school whose administration is “very oppressive” toward women and their rights, found comfort in social media.

“I think social media movements like #HijaAko exist because there is something innately wrong with what we have now,” she says, underscoring the fast response and support one can get in social media compared to the “slow bureaucratic process” of administrative systems.

She asks: “Is there a way to balance both?”

Insensitivity

Government agencies such as the Philippine Commission on Women and the Philippine National Police in coordination with local government units actively assist victim-survivors in some cases, according to Sen. Risa Hontiveros, chair of the Senate committee on women, children and family relations.

“But we still receive reports of victim-survivors whose stories are sometimes dismissed by these institutions themselves, or handled insensitively,” Hontiveros says, adding:

“Therefore, it’s not surprising that many victim-survivors resort to calling out their abusers on social media because sometimes that’s the only space left where some of them feel they retain some measure of empowerment and agency, and can really express their outrage and call for justice.”

One institution aimed at helping victim-survivors is the PNP Women and Children Protection Center (WCPC). It is mandated to protect women and children against abuse and other gender-based violence by conducting investigations and initiating necessary actions to ensure the arrest and prompt prosecution of offenders.

When a person reports violence to the WCPC or the women’s desk at police stations, the first response is to conduct an initial review of the incident and record it on the “pink blotter” exclusive to such cases, Police Colonel Joy Tomboc, the WCPC chief for Anti-Violence for Children and Women’s Desk, tells the Inquirer.

The assessment will determine the victim’s level of risk and the appropriate assistance to be rendered, such as health care, psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation, by concerned government and private agencies.

Tomboc says the lack of facilities or shelters for victims, especially of domestic abuse, is compensated by the immediate issuance of temporary barangay protection orders to shield them from their attackers.

The needs of every victim vary, and not everyone will want to file a case, Tomboc says.

“Victims of abuse usually have many considerations when filing a report,” she says. “Some are under threat from their partners or are economically dependent on their husbands.”

A prevailing challenge in filing a complaint or a case is getting the victim to actually file one, says litigation lawyer Alex Castro.

“Most clients are not sure whether what happened to them constitutes sexual abuse or harassment,” Castro says. Sometimes, she adds, fear of the offender’s retaliation holds back the victim-survivor, thus perpetuating the culture of impunity.

In pursuing a case, a victim has to file a complaint at the office of the city prosecutor, which will determine whether it has merit to proceed to trial and the filing of a criminal case.

But Castro once encountered a prosecutor who employed a “skewed line of questioning”—he asked the victim how much she had drunk on the night she experienced sexual violence.

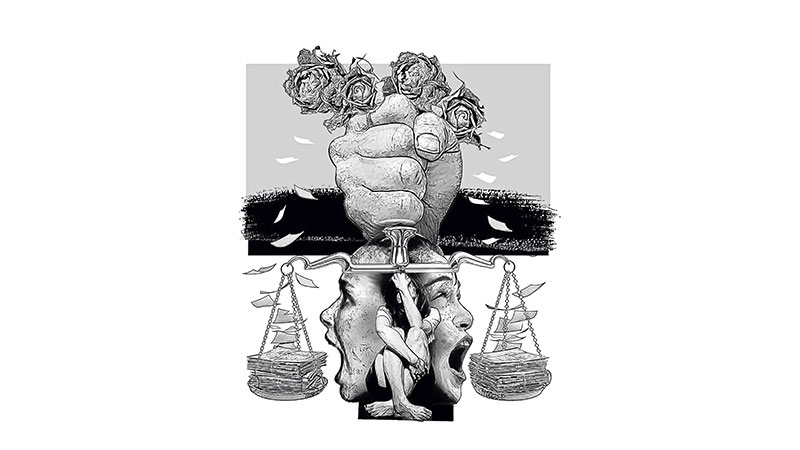

Burden of proof

“That was very detrimental [to the client]. She was feeling suicidal because she thought it was her fault,” Castro says, adding that it shows how such questions affect those seeking justice.

Human rights lawyer Kathy Panguban says there is a need to recognize the stigma that victims of sexual abuse bear when it comes to the legal process.

“Legally speaking, that’s the nature of criminal cases. The burden of proof is always on the one who alleges that a crime has been committed against them,” she says.

But what is different with rape cases is that aside from proving the case, “you also have to prove in the public’s eyes that you did not ask for it,” Panguban says.

Psychological trauma surfaces in the victim in the process of fighting back, says Andrea Martinez, a psychology professor at UP Manila.

“Imagine this: You’ve been raped. Then when you are being interviewed, you have to prove that it’s been done to you, to the point where you have to relive the experience which you would rather forget,” Martinez says. She says this is why some choose to be silent.

Martinez cites the case of a child who was raped by her father for six years but the first and last assaults were the only instances that she remembered: “That’s also a manifestation of trauma; she had forgotten [what happened] in between.”

The youngest survivor Martinez has dealt with is a 2-year-old who did not want to pass through the street where her father, her attacker, lives. The rape was discovered because the child kept complaining of pain in her anus; she also had a urinary tract infection and discharge at her tender age.

Other consequences of sexual abuse are depression, drug addiction, unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases, Martinez says.

‘Flawed’ laws

Senator Hontiveros says that despite legislation, such as Republic Act No. 8353 or the Anti-Rape Law of 1997, “these laws are not often implemented with sensitivity to the victim-survivors.”

“We have these empowering instruments, but in hands, minds and hearts that are not yet gender-sensitive, they can be very crude instruments, or they can bring more harm,” she says.

Castro observes that laws supposedly addressing the issue of sexual abuse are “very flawed.” Many laws have narrow scopes, unable to offer enough protection to women and children, she says.

On Dec. 1, House Bill No. 7836, which seeks to amend Republic Act No. 7610, or the Special Protection of Children Against Abuse, Exploitation and Discrimination Act, was passed on final reading in the House of Representatives.

The measure is aimed at raising the age of statutory rape in the Philippines from 12 to 16.

It expands the definition of rape, provides stiffer penalties for rape, sexual exploitation and abuse, and shifts the burden of proof of consent to the perpetrator. It also states that a subsequent marriage between the rape victim and the offender will not extinguish criminal liability. INQ