(First of three parts)

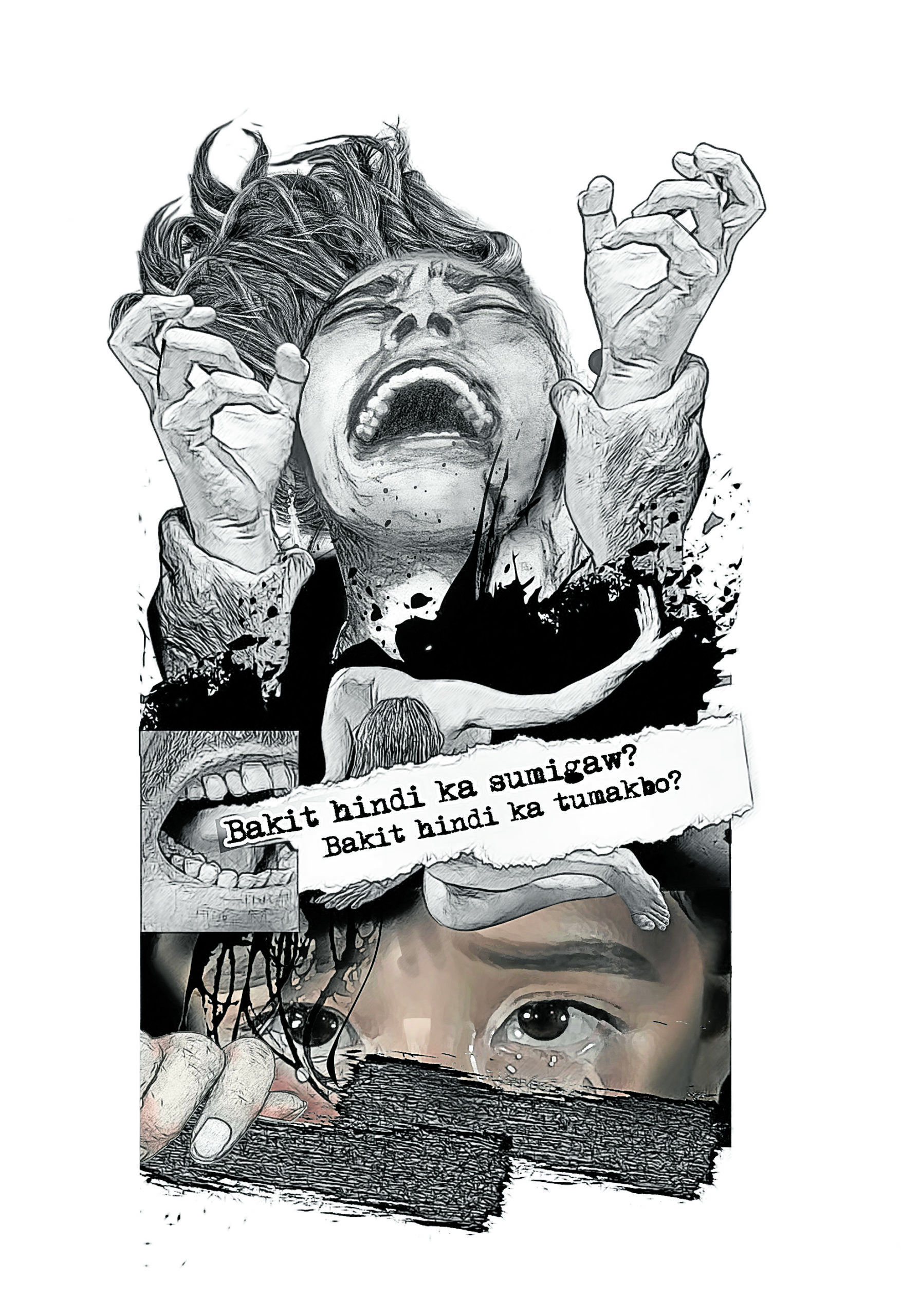

What were you wearing? How much did you drink? Why didn’t you shout? Why didn’t you run away?

Was it pleasurable? “Nasarapan ka ba?”As though they hadn’t been through the worst, survivors of sexual abuse—rape in particular—still find themselves thus interrogated by the very people supposed to come to their aid.

“It appears that it’s always the victim’s shortcoming. That they didn’t do anything [to protect] themselves from being raped, like not wearing a short [skirt],” said Kathy Panguban, a legal counsel of the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers.

Rights advocates say victim-blaming stems from longstanding traditions of a patriarchal society that allow the perpetuation of sexual violence—a systemic problem that demands a cultural and structural “overhaul.”

The overhaul should ideally start from the top, but things don’t look promising in that respect with President Duterte’s well-known penchant for cracking “rape jokes.”

During a postcalamity briefing on Typhoon “Rolly” (international name: Goni), the world’s strongest storm this year that devastated the Bicol region, Mr. Duterte managed to poke fun at local official Marvel Clavecilla for supposedly having “too many women.” Clavecilla, the presidential adviser on Bicol affairs, gamely replied that, in fact, he was “undersexed.” During a campaign sortie in April 2016, then-presidential candidate Duterte talked about Australian missionary Jacqueline Hamill who was raped and murdered in a prison riot in Davao City. He said Hamill was “so beautiful” and he should have been first in line.

Sending the message

In 2017, he said he would “congratulate” anyone who raped a Miss Universe. In 2018, he said Davao City had the biggest number of rape cases in the country because there were “many beautiful women” there. In 2019, upon signing an order pardoning the offenses of Philippine Military Academy underclassmen, he quipped that one of the infractions was rape. Malacañang officials consistently play down the President’s lewd remarks, saying these were his way of making people laugh. But humor is supposed to be funny, not something that “puts down people” and “condones rape culture and violence,” said Malou Alcid, a professor of social work at the University of the Philippines.

“When no less than the President of the Philippines issues statements that put down women, makes jokes of women and their objectification, it sends the message to boys and men that this is OK, that nothing ought to be changed,” Alcid said.

Cops’ offenses

For Sen. Risa Hontiveros, a leader naturally sets the tone of the community he is leading, so it is a “major red flag” that Mr. Duterte enforces a “normative” behavior against women and “legitimizes” rape culture.

When the COVID-19 pandemic put the entire Luzon under lockdown, Hontiveros, along with women’s groups, warned of the possible surge in domestic and sexual abuse.

“Because of the proximity in the home and added stress due to economic hardship brought by the enhanced community quarantine, Filipino women and children who are living with their abusers become more vulnerable to violence,” the senator said in a press statement.

Child abuse cases

Recent data from the Philippine National Police showed a drop in reported violence against women and children cases from 1,113 in February to 984 in March and 667 in April—when the strictest quarantine measures were imposed. It started to increase again in May, 897, and June, 966.

The number of child rape cases, considerably higher compared to women, also declined from 464 in March to 294 in April, but immediately rose to 488, or 65.99 percent, in May.

Reported child abuse cases were lowest in April with 423 but increased to 703, or 66.19 percent, in May. But even amid a pandemic, there is no particular circumstance in which sexual violence occurs. Sometimes, it is perpetrated by police.

‘Sex-for-pass’ scheme

Last July, Police Staff Sergeants Randy Ramos and Marawi Torda of San Juan, Ilocos Sur, were held responsible for the murder of a 15-year-old rape victim and the rape of her 18-year-old cousin. The two girls filed complaints of sexual assault against Ramos and Torda at the police station. A few days later, the 15-year-old was shot and killed by two men on a motorcycle while she was heading home after following up on her complaint.

At the height of the pandemic-induced lockdown, there were also reports on a “sex-for-pass” scheme in which police officers at checkpoints sexually abused women in exchange for quarantine passes. But police-perpetrated sexual abuse is not indicative of the social environment in the police force toward sexual violence, said Police Col. Joy Tomboc, the chief of the PNP Women and Children Protection Center’s antiviolence against women and children’s desk.

Violence against women is not tolerated in the PNP, and administrative actions and investigations are in place to hold offenders accountable, Tomboc said. “Our leadership always promotes the protection of and respect for women’s and children’s rights.”

‘Kalakaran’

In October 2018, the PNP was tagged for its “rape culture” in the wake of reports that PO1 Eduardo Valencia of the Manila Police District (MPD) had raped a 15-year-old girl in exchange for the freedom of her parents who were detained on drug charges. Valencia claimed that what he had done was the “kalakaran”—SOP (or standard operating procedure—in the police force. The then MPD chief, Supt. Guillermo Eleazar, invited the press to cover Valencia’s arrest, which, he said, should send a message to all cops planning to do the same.

But less than two weeks later, it was reported that police officers Jayson Cudiamat and Severio Montalban III had raped a woman taken in for illegal gambling, in exchange for her freedom.

Entitlement

Sexual violence is pervasive “because women are still not equal to men,” Hontiveros said, adding that abusive men translated this perceived power into actual assault, rape, or sexual harassment.

“There is an entitlement on their part over [women’s] bodies,” the senator said.

It is also a “byproduct of a patriarchal system” where men still “hold primary power in political leadership, in executive positions, and in social privilege, and the economic advantage that these privileges put them at,” she added.

Overhauling the existing social environment entails collective action, in which men and other sectors, such as the LGBT community, play an active role in eliminating sexual violence, Alcid said.

“The burden of continuously struggling for better life conditions should not only be on the shoulders of women just because they are the ones being victimized,” she said.

It is equally, if not more, important that male advocates against gender-based violence take the leap with women, she added, because “men are inclined to listen to each other,” hence encouraging community education that will ultimately help in fighting sexual abuse. INQ