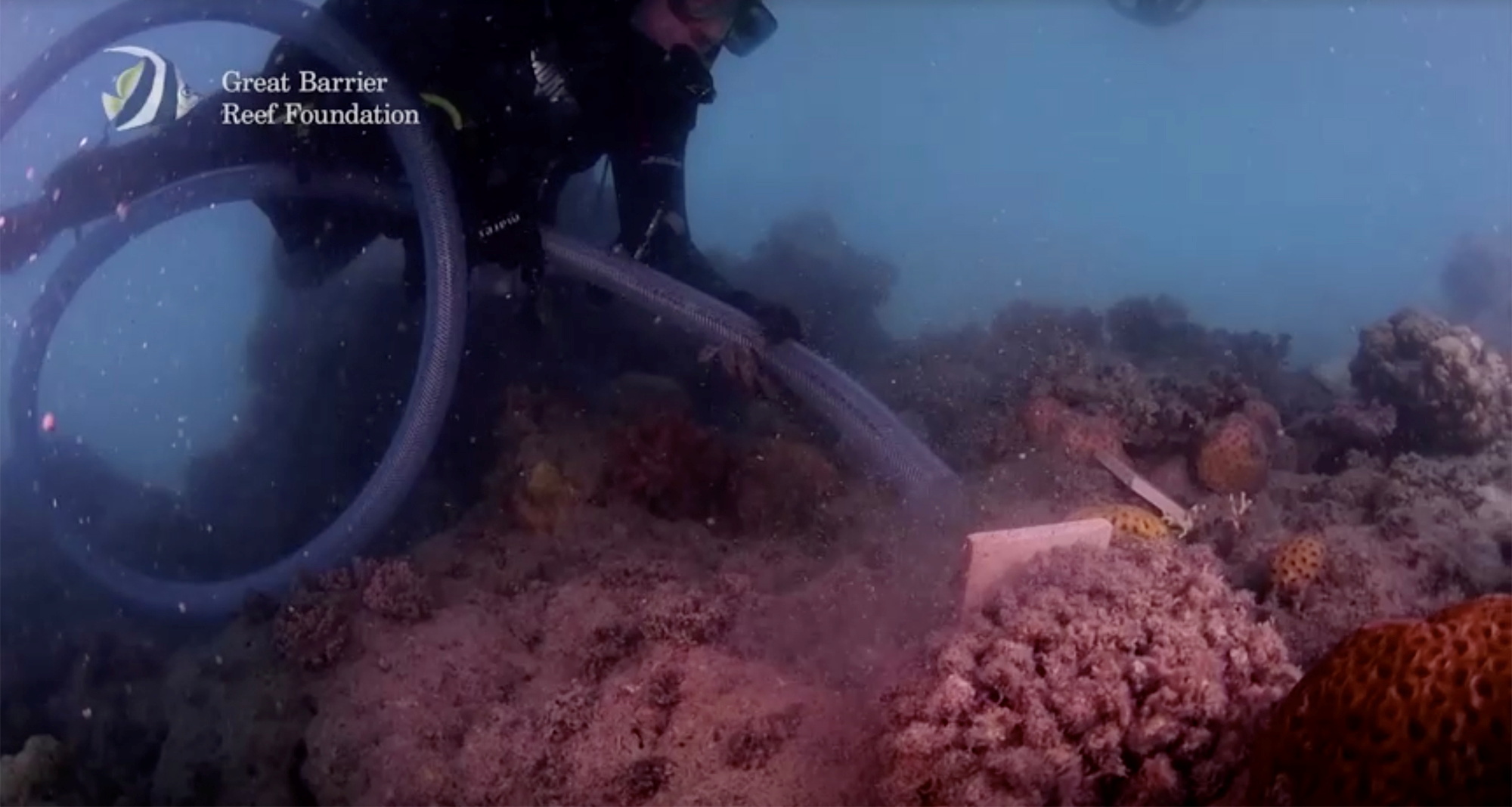

A diver deploys coral larvae onto a reef in Whitsunday Islands, on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, in this still frame taken from a handout video. Great Barrier Reef Foundation/Handout via REUTERS TV

SYDNEY — Coral populations from Australia’s first “Coral IVF” trial on the Great Barrier Reef in 2016 have not only survived recent bleaching events but are on track to reproduce and spawn next year, researchers say.

“I’m really excited,” said Peter Harrison, director of Southern Cross University’s Marine Ecology Research Centre, who led the development of the larvae restoration technique which involves collecting coral sperm and eggs during the annual mass spawning on the reef.

After culturing larvae in specially designed enclosures for about a week, scientists distribute them to parts of the reef damaged by bleaching and in need of live coral.

Harrison’s team, working with the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, first used the tactic just off Heron Island in 2016, where more than 60 corals are now on the way to being the first re-established reproducing population on the reef through Coral IVF.

“This proves that the larvae restoration technique works just as we predicted and we can grow very large corals from tiny microscopic larvae within just a few years,” Harrison said after visiting the restoration site in early December.

The corals varied in diameter, from just a few centimeters to the size of a dinner plate, and were healthy, despite a bleaching event that hit Heron Island in March.

The March bleaching was the reef’s most extensive yet, scientists said, and the third one in five years.

Bleaching occurs when hotter water destroys the algae which corals feed on, causing them to turn white.

A recent study from James Cook University found the reef had lost more than half of its coral in the past three decades and raised concern that it is less able to recover from mass bleaching events.

The Great Barrier Reef runs 2,300 km (1,429 miles) down Australia’s northeast coast spanning an area half the size of Texas. It was world heritage-listed in 1981 by UNESCO as the most extensive and spectacular coral reef ecosystem on the planet.