Learning from the Cagayan Valley deluge

TUGUEGARAO CITY, Cagayan, Philippines — When deadly flash floods and landslides strike unsuspecting communities, people who lost their property and loved ones will almost always point their fingers at illegal logging or mining.

But ideally, local governments have been prepared for these disasters due to geological hazard maps that have been put out between 2010 and 2011 by government scientists, according to Clarence Baguilat, former regional director of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR).

These are not the first hazard maps developed by the government, which has archival materials on typhoons, landslides, floods and volcanic eruptions that date back to the Spanish colonial era.

The Philippines has always been classified as vulnerable to natural calamities due to its geography and terrain. In the last decade, geohazard maps featured scales that were improved from 1:20,000 to a larger scale of 1:50,000 (1 centimeter represents half a kilometer).

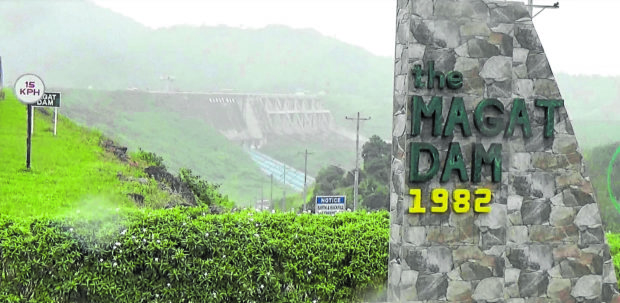

WATER RELEASE Residents in low-lying towns and cities along the Cagayan River and its tributaries in Cagayan Valley region expect floodwaters to swamp their villages whenever Magat Dam in Isabela releases water. In this 2018 photo, the dam in Ramon town releases water into the Magat River, a major tributary of Cagayan River, in preparation for the landfall of Typhoon “Ompong” (international name: Mangkhut). —RICHARD A. REYES

Political will

Baguilat, a geologist, said this scale was made particularly for “developed or developing settlements and populated areas.”

“These [geohazard maps] are good enough tools to begin and work with,” said Baguilat, who had participated in the mapping project.

Article continues after this advertisementHow it has been used is another matter.

Article continues after this advertisementBaguilat said the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB), which spearheaded the geohazard mapping project, should “do a post evaluation of local governments to determine how they used their geohazard maps” in light of the latest disasters, such as the widespread flooding in Cagayan Valley last week.

He said the review could also determine how hazard information had impacted their planning and policymaking on the environment and land use.

“That will also determine who are those politicians with political will and those who just wait for a disaster to happen before they do anything at all,” Baguilat told the Inquirer.

The geohazard mapping project was initiated in 2010 when Typhoon “Juan” (international name: Megi) tore through Cagayan and Isabela, raising concerns about food supply because of the devastation of rice farms in the two provinces.

‘PEPENG’S’ WRATH In this photo taken in 2009, floods triggered by rain dumped by Typhoon “Pepeng” (Parma) leave a trail of destruction in the village of Tumana in Rosales town, Pangasinan province. —WILLIE LOMIBAO

Pangasinan’s experience

In 2009, raging waters triggered by Typhoon “Pepeng” (Parma) swamped towns and villages in northern Luzon.

Like the floods that forced Cagayanos to flee to rooftops on Nov. 14, Pangasinan residents spent hours waiting for help atop their houses in 2009 when the San Roque Dam opened its floodgates as nonstop rains inundated towns.

At least 36 towns in Pangasinan were submerged due to the abrupt and excessive volume of water released from the dam, causing loss of lives and much damage to crops and lands.

The peak of the water discharge from San Roque was recorded at 3 a.m. on Oct. 9, 2009, when the dam’s elevation was at 289.05 meters above sea level. The watershed’s maximum critical level is 180 masl.

At that time, all six gates (or 27 meters) of the dam were opened, spilling 5,072 cubic meters per second volume of water (each cubic meter is equivalent to the size of a “balikbayan” box of water).

The gates of San Roque Dam were closed on Oct. 12 when water was down to 280 masl, the spilling mark. By then, many dikes had been breached in several Pangasinan towns.

CITY FLOODS A large portion of downtown Tuguegarao City in Cagayan province is submerged as Cagayan River breached its banks due to heavy rain accompanying Typhoon “Ulysses” (Vamco) and the release of water from Magat Dam in Isabela province on Nov. 13 and Nov. 14. —DAVID TE/CONTRIBUTOR

Extra careful

San Roque Dam releases water to the Agno River, Luzon’s third longest river, next to Cagayan and Pampanga rivers.

After the 2009 massive flooding, National Power Corp. (Napocor), which operates the San Roque Dam, became extra careful in opening the dam’s gates to release water.

The dam opened its gates in 2011, 2012, 2015, 2016 and 2018, but these did not cause floods as the release was calibrated and strictly followed protocols.

“Normally, Napocor starts opening gates when water reaches 280 masl, depending on the typhoon intensity, water inflow and rainfall intensity,” said Tom Valdez, vice president for community affairs of San Roque Power Corp.

In 2012, then President Benigno Aquino III placed the entire country under a state of calamity following the damage wrought by Typhoon “Pablo” (Bopha).

POWER AND IRRIGATION Magat Dam, built from 1976 to 1982, is one of the major sources of electricity for the Luzon power grid and irrigation water for farms in Isabela. —VILLAMOR VISAYA JR.

Supertyphoon ‘Yolanda’

The DENR began advising local governments to examine their geohazard maps for flood prone areas in their localities so they could launch evacuations.

The maps, however, would not have anticipated the strength of Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (Haiyan) in 2013 which wreaked havoc in Leyte and neighboring provinces.

The subsequent typhoons were fiercer, such as Typhoon “Ompong” (Mangkhut) in September 2018 and the series of storms that struck late November that year.

“As soon as the MGB finished the geohazard mapping of the whole country way back 2010-2011, they went on a massive information and educational campaign covering all local governments, distributing geohazard maps and giving them (city and municipal disaster managers) basic education as to how they should read the maps and incorporate them in their land-use planning and disaster management, or at least that was the plan,” Baguilat said.

Budget issue

In many cases, budgetary issues plagued towns that intended to build new communities for people who would need to leave danger zones.

The social impact of relocating communities was also staggering. When a massive landslide buried a community called Little Kibungan in La Trinidad, Benguet province, due to Typhoon Pepeng, then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo facilitated the relocation.

Eleven years later, many families in Little Kibungan have not moved owing to issues over ancestral land rights at their relocation site, their refusal to leave relatives behind, and new confidence about their safety when government engineers put up a wall around a vulnerable mountain.

“Economics would come into play [when interpreting the geohazard maps],” Baguilat said.

He said local governments must decide which is more costly: Moving out people from high-risk areas and settling them to safer areas or letting them remain but providing and maintaining engineering and disaster control measures.

At the height of the massive flooding in Cagayan Valley, 47,600 families, or 164,400 people, were affected. Since last month, four typhoons that crossed Luzon and affected Cagayan Valley left farm damage worth at least P2 billion.

At least 29 fatalities were recorded due to the severe flooding that hit the region. Most of them died due to drowning and landslides.

Most local governments have yet to collaborate as clusters in addressing danger zones and to pool resources and “build better.”

“Geohazards and the environment know no political boundaries as they are governed by nature,” Baguilat said.

—Reports from Vincent Cabreza, Yolanda Sotelo and Villamor Visaya Jr.