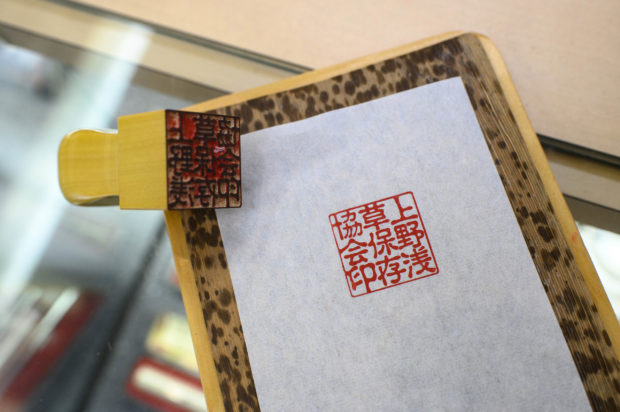

STAMPED OUT? Traditional ink stamps known as “hanko” are used to sign everything from delivery receipts to marriage certificates in Japan. A push to phase them out faces an uphill struggle. —AFP

TOKYO—Japan’s new prime minister is declaring war, but there’s no danger of an international conflict: the target of his ire is the humble ink stamp known as “hanko.”

It might seem paradoxical in a country often assumed to be a futuristic tech-savvy paradise, but Japan’s business world and bureaucracy remain heavily dependent on paper documents, hand-stamped with approval.

The drawbacks to hanko, which are used for everything from delivery receipts to marriage certificates, have become increasing clear during the coronavirus pandemic—many Japanese were unable to work from home because they had to physically stamp documents in the office.

Now, Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga is on a push to digitize the nation, but he faces an uphill struggle when it comes to the stamps, which range from mass-produced plastic ones to handcarved wooden versions used on special occasions.

Miniature characters

Artisan stamp maker Takahiro Makino, who painstakingly carves miniature characters into each unique piece he makes, isn’t too worried about the drive.

“We shouldn’t keep using things that aren’t necessary. But on the other hand, an object of value will survive no matter what,” he told Agence France- Presse (AFP) at his workshop in downtown Tokyo.

For each stamp, he carefully paints the name of the person or company that will adorn it, before beginning the delicate work of chiseling.

Each stamp will “carry the personality of each craftsman,” the 44-year-old said.

Sturdy handmade stamps like Makino’s cost several hundred dollars and are often given by parents to children as a coming-of-age gift—an essential tool for a responsible adult.

Their unique design is registered at city hall so it can be verified when used to validate property deeds and other important documents.

Stamp it out

For everyday signatures, people use smaller, cheaper mass-produced seals, and the stamps are often a key part of an office worker’s daily grind.

That’s precisely what Suga and his administrative reform minister Taro Kono are keen to stamp out.

“I will insist no seals be required for administrative procedures unless they are justified,” Kono said at a press conference soon after his appointment.

Examples of hanko excess aren’t hard to come by, with Kono himself citing documents reportedly stamped more than 40 times by different officials.

And Japanese residents say the stamps are sometimes even required in digital transactions.

“One time, I was asked to stamp a piece of paper, scan it, and then attach it to an electricity bill,” laughed Sayuri Wataya, 55, an editor.

The government’s push has borne some fruit, with Japan’s national police agency saying it will stop the mandatory use of the seals for casual document approvals from next year.

Big Japanese companies, including Hitachi, have also vowed to abolish hanko use in internal paperwork.

Deeper-rooted issues

Observers warn, however, that streamlining the reams of paperwork that currently swamp Japanese companies and government offices involves deeper-rooted issues.

Japan Research Institute manager Takayuki Watanabe sees the stamps as part of Japan’s hierarchical business culture.

To get a decision approved, an employee often needs stamped approval from colleagues above them in rank, one by one, he told AFP.

“First, you need a seal from your superior, then the team leader, the section chief and the department director,” he said. “It’s a no-no to skip those in the middle.”

The top boss usually stamps their seal upright on the left of a document, with lower-ranking employees all tilting their stamps toward it as if “bowing.”

Seal of approval

Having the whole team’s stamps shows a collective decision has been made, Watanabe said.

“It’s like, ‘I stamped my seal to approve it but you did it before me, so you should be held liable,’” explained accountant Tetsuya Katayama.

“No one wants to take responsibility in Japan,” he said.

Watanabe warned that the government’s antihanko campaign will founder unless Japanese workers can break out of that mentality.

“Even if they digitize paperwork, they will end up pressing computer buttons as many times (as they stamped),” he said.

“People have to steel themselves to take certain responsibility.”

At the All Japan Hanko Industry Association, senior official Keiichi Fukushima is a perhaps unlikely advocate for scaling back stamping.

“People have used hanko stamps just for the sake of stamping,” he concedes, insisting that they are used only when necessary will clarify when they’re actually needed and “may be a good chance to prove how important the custom of hanko is.”