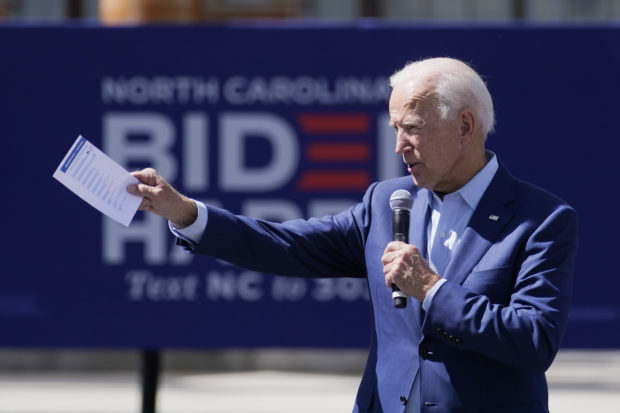

FILE – In this Sept. 23, 2020, file photo Democratic presidential candidate former Vice President Joe Biden speaks during a Biden for President Black economic summit at Camp North End in Charlotte, N.C. The final stretch of a presidential campaign is typically a nonstop mix of travel, caffeine and adrenaline. But as the worst pandemic in a century bears down on the United States, Joe Biden is taking a lower key approach. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster, File)

WILMINGTON, Del. — The final stretch of a presidential campaign is typically a nonstop mix of travel, caffeine and adrenaline. But as the worst pandemic in a century bears down on the United States, Joe Biden is taking a lower key approach.

Since his Aug. 11 selection of California Sen. Kamala Harris as his running mate, Biden has had 22 days where he either didn’t make public appearances, held only virtual fundraisers or ventured from his Delaware home solely for church, according to an Associated Press analysis of his schedules.

He made 12 visits outside of Delaware during that period, including a trip to Washington scheduled for Friday to pay respects to the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

During the same time, President Donald Trump had 24 trips that took him to 17 different states, not counting a personal visit to New York to see his ailing brother in the hospital or weekend golf outings.

Biden’s aides insist his approach is intentional, showcasing his respect for public health guidelines aimed at preventing the spread of the coronavirus and presenting a responsible contrast with Trump, who has resumed large-scale campaign rallies — sometimes over the objections of local officials.

Still, some Democrats say it’s critical that Biden infuse his campaign with more energy.

Texas Democratic Party Chairman Gilberto Hinojosa said not traveling because of the pandemic was a “pretty lame excuse.”

“I thought he had his own plane,” Hinojosa said. “He doesn’t have to sit with one space between another person on a commercial airline like I would.”

Hinojosa argued that Biden prioritizing visits to Texas and Arizona could boost Latino turnout and potentially reduce the pressure on him to sweep Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania — where he has focused much of his travel so far.

“We are campaigning safely and effectively, and our message is reaching voters in battleground states and generating the enthusiasm and energy we need to beat Donald Trump,” said Biden spokesman TJ Ducklo.

The race between Biden and Trump has been generally consistent for months. Biden has maintained a comfortable lead in most national polls and has an advantage, though narrower, in many of the battleground states that will decide the election.

But polls that showed competitive races or even Democratic advantages in traditionally Republican states proved to be false indicators for Democrats in 2016.

Four years later, Biden faces persistent questions about whether his campaign is organizing and connecting with voters. When he visited Charlotte, North Carolina, on Wednesday for a Black economic summit, Collette Alston, chairwoman of the local African American Caucus, said she only found out with one day’s notice — when she saw it on TV.

Just 16 people attended the event and Alston warned that Biden wasn’t reaching locals she thinks he needs to — “the people that are like, I don’t care, I really don’t want to vote.”

“I do believe that he can win North Carolina,” Alton said. “Can he win it based on what he’s doing right now? No. That’s not the way to win it.”

Biden’s swing state visits often seem tailor-made for a television package: A small, socially distanced roundtable or town hall, always with fewer than 25 people; occasionally a stop at a local business or a visit with first responders; and then hours of back-to-back local media interviews.

Beyond traveling more, Biden is being urged by some Democrats to expand his message. While he has given standalone speeches on issues like criminal justice reform, climate change and, last weekend, the Supreme Court vacancy, Biden largely ignores those issues during his campaign stops.

When he appears before voters, he’s generally laser-focused on the virus and the Trump administration’s mismanaging of it.

When a grand jury decided Wednesday not to bring charges against police officers directly involved in the killing of Breonna Taylor, he offered condolences to her mother but declined to comment about the specifics of the case on camera. He later issued a more detailed written statement.

David Axelrod, Barack Obama’s former strategist and adviser, said the Biden campaign is “wise” to concentrate on the pandemic because it’s an “anchor around the President’s neck.” But he said it would be a “missed opportunity” for Biden if he didn’t speak up more about the Supreme Court going forward, especially the impact it could have on healthcare.

“The future of the Affordable Care Act and particularly the future of protections for people with preexisting conditions is a very close issue, and it’s what drove Democrats to victory in 2018,” Axelrod said.

Biden’s aides say the relatively light schedule, small events and message discipline reflect the biggest issue still confronting most Americans today: the coronavirus pandemic. Biden also has sought to offer a responsible contrast to Trump and his rallies, where thousands forgo masks.

“Every time Trump shows up and has a mask-less rally and says this thing is overblown, Democrats are winning the COVID battle,” said Jim Kessler, an executive vice president of the moderate Democratic group Third Way.

Biden maintains a vigorous schedule even when he’s not traveling. His campaign has become a fundraising powerhouse through largely virtual events. He raised a record $364 million in August that has allowed him to blanket the airwaves across the country and outspend Trump.

Still, Trump sees the contrast in travel as an opportunity to argue that his packed schedule shows he’s outworking Biden. The president seized on the Biden campaign’s announcement shortly before 9:30 a.m. Thursday that he wouldn’t have any public events for the day.

Biden spent the day preparing for his first debate against Trump next week.

“Did you see he did a lid this morning again?” Trump said of Biden during a rally Thursday night at an airport hangar in Jacksonville, Florida. “A lid is when you put out word you’re not going to be campaigning today. So he does a lid all the time. … I’m in Texas. I’m in Ohio. I’m in North Carolina, South Carolina. I’m in Michigan. I’m all over the place.”

Biden’s aides counter that they see evidence in public and private polling that the virus remains top of mind for most voters, and that they have a compelling case to make that much of the crisis is Trump’s fault. They also say their focus on small, high-impact events gets results.

Still, the cautious approach isn’t shared by Biden’s wife, Jill, who has already ventured as far away as Maine and spent Thursday making four stops in Virginia. She’s going to Iowa, another state her husband has yet to visit in recent months, on Saturday.

Hillary Scholten, a Democrat seeking an open House seat in Michigan, spent a morning last week touring a food bank in Grand Rapids, the state’s second-largest city, with Jill Biden. She’s aware that Joe Biden may not follow suit.

“People would want to see him here,” Scholten said. “That being said, there is a global pandemic.”