Martial law museum to rise on UP Diliman campus

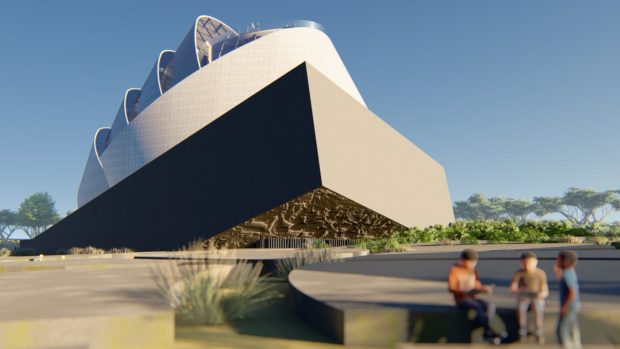

The museum’s design combines the imagery of a closed fist and that of a flower, borne out of the Brutalist architectural style (simple, block-like structures). The four young architects who crafted the design said it was a deliberate play on the “brutal” historical era and of the architectural style that governed much of Marcosian edifices, like the Cultural Center of the Philippines and the Philippine International Convention Center. PHOTO from HRVVMC

MANILA, Philippines — With every passing day, activist playwright Bonifacio “Boni” Ilagan worries that the Marcoses are gaining ground in the vicious battle against historical revisionism.

The horrors he endured under the Marcos regime remains vivid in his mind, but social media has eroded the country’s collective memories, he noted.

As false narratives about Ferdinand Marcos are systematically amplified by networks of disinformation, Ilagan feels that “my story, and the story of all those who were tyrannized by martial law, are being delegitimized.”

“I belong to a generation that is slowly but surely vanishing,” he said. “For the remaining days of my life, I feel the need to tell and retell my story, and the story of the rest of us who fought and survived martial law.”

But now, what better pushback than a P500-million concrete memorial that would house, permanently, their lived experiences under the late dictator’s reign?

Article continues after this advertisementOpen for bidding

On Monday — two days before the 48th anniversary of the declaration of martial law on Sept. 23, 1972 — the Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission (HRVVMC) finally opens for bidding the construction of the Freedom Memorial Museum — the first such center dedicated to the victims of Marcos’ brutal regime — atop a 1.4-hectare lot inside the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman.

Article continues after this advertisementOnce completed, it would be the first and only state-sponsored museum that officially recognizes the atrocities committed during martial law, said Carmelo Crisanto, executive director of the commission.

The HRVVMC was created under Republic Act No. 10368, which aims to grant reparations and recognition for the victims of martial law.

But part of transitional justice for martial law victims is also “the right to correct memory,” Crisanto noted.

Part of why the myth of Marcos’ rule as a “golden era for the Philippines” persists, he says, is the edifices built during his time.

“There is nothing that counters those kinds of monuments,” he said in an interview with the Inquirer. “[That’s why] the Freedom Memorial is a very important part of that infrastructure of memory. It is a memorial… that gets government [to say] mea culpa.”

More than a building

Such a museum won’t be “just any other government building,” Crisanto said. “It is filled with emotions, controversy and apprehension.”

It is also very much different from the privately funded Bantayog ng mga Bayani in Quezon City: the meters-long black marble on which the names of martial law heroes and martyrs are etched.

A state-sponsored museum immortalizing the atrocities of martial rule, Crisanto said, is akin to the government apologizing for unleashing state forces upon hapless citizens—and a reminder for succeeding administrations not to make the same mistake.

Plans for such a museum started to crystallize in 2017, when the commission signed a memorandum of agreement with UP. The state university was a natural choice for the museum, having been a prominent stage for the student-led resistance against Marcos.

The commission is looking at a 1.4-hectare lot near the College of Fine Arts. The bidding contracts that would be posted are for the relocation of the UP Community Affairs Office (P80 million), as well as the P475-million contract for the museum construction itself.

Fist-cum-flower

The museum’s design is a fist-cum-flower borne out of the Brutalist architectural style (that is, simple, block-like structures). The four young architects who crafted the design said it was a deliberate play on the “brutal” historical era and of the architectural style that governed much of Marcosian edifices, like the Cultural Center of the Philippines and the Philippine International Convention Center.

The fusion of both the fist and flower, they said, symbolized how Marcos’ reign was toppled by the largely peaceful resistance of the 1986 People Power Revolution.

Every part of the museum aims to tell a story, Crisanto said. Visitors would have to go through “prison bar” entrance gates as a reminder of the several restrictions imposed by martial rule. They will visit a “torture gallery” that would house the different interrogation tools used against dissidents.

At the heart of the museum, they would see the Aviation Security Command (Avsecom) van where government assassins of prominent Marcos critic Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr. took his body, after shooting him dead upon his arrival at the Manila international airport on Sunday afternoon of Aug. 21, 1983.

For his part, Ilagan, himself an artist, hoped to see “authentic memorabilia vintage 1970s”: artifacts that serve to testify to the stories as well as a theater “dedicated to performances reliving the heroism and martyrdom of all Filipinos who fought the dictatorship.”

To this end, Crisanto called on martial law victims “if they can donate or share with us any artifact, memento made by them, we would like to accumulate as much as share them with the general public.”

“It’s unfortunate (that it took us this long), but building that museum is one big step forward. Paying the victims despite the small number is a great leap forward,” he said. Ilagan said he hopes to see the museum built and inaugurated in his lifetime.

“It shall be a precious repository of our stories and a testament to the commitment of Filipinos willing to defy dictatorships and to stand up for truth, justice and democracy,” he said.