JAKARTA — The rate at which Indonesia is losing farmers is a cause for concern. If it continues, Indonesia is likely to have no farmers left in 50 years. What will we eat?

“Well, we will be hungry,” said Adang Parman, 58, a farmer from Ciburial village in West Java. Every day, the father of three heads out to the field at the break of dawn to pull out weeds, water his plants or pluck vegetables from his rows of plants. His sons, meanwhile, plow the land with a handheld walking tractor.

Adang has been working in the fields for more than 40 years. The work is demanding and laborious. This probably explains why fewer and fewer people are taking up the profession.

The country lost 5.1 million farmers between 2003 and 2013, with their numbers falling to 26 million, according to Statistics Indonesia (BPS). The trend is expected to continue in the next few years. At this rate, Indonesia would lose all its farmers by 2063.

“A large proportion of young people view agricultural work as low-wage, manual labor that is more suited to those from poor backgrounds who have limited education,” a 2016 SMERU Research Institute report reads.

Agriculture is a huge contributor to Indonesia’s economy. Around 29 percent of the Indonesian workforce works in the agriculture, fisheries and livestock sector, which contributes nearly 13 percent to the country’s GDP. It is the third-biggest contributor to the economy after manufacturing and trade, according to Statistics Indonesia (BPS) data.

Fewer young people are pursuing farming as a profession compared with previous generations. Only 23 percent of the country’s 14.2 million people aged between 15 and 24 worked in the agriculture, forestry and fishery sectors in 2019, data from the National Labor Force Survey showed.

Asep, Tisna, Dika – Adang’s three sons – represent the minority of young people venturing into agriculture, following in their father’s footsteps.

With a population of just 12,000 — less than a quarter the capacity of a major football stadium — Ciburial offers vast expanses of lush, fertile land, perfect for farming. This is not the case elsewhere in Indonesia.

Between 2013 and 2019, Indonesia’s agricultural land decreased to 7.46 million hectares from 7.75 million ha, according to data collected by the Agrarian and Spatial Planning Ministry, BPS and several other government institutions.

Problems like increasing production costs, changes in weather and pest attacks have also pushed farmers to change professions, with land owners either converting land to other uses or selling it, the SMERU report states.

So, what went wrong? How can we support more farmers like Adang and his family? The Jakarta Post spoke to farmers, agriculture and food companies, policymakers and experts on the challenges and opportunities for Indonesia’s farmers and the agriculture sector.

Not earning enough

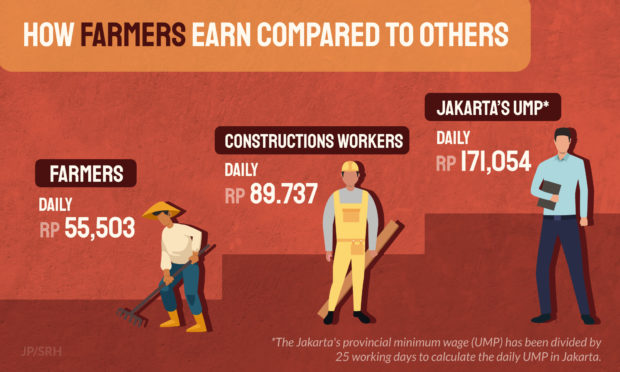

Rp 55,503 (US$3.81). That is how much farmers earned on average per day as of June, according to nationwide data compiled by Statistics Indonesia (BPS). Compare that with Rp 89,737 per day for construction workers.

In the concrete jungle of Jakarta, the official minimum wage is Rp 3.9 million per month, roughly Rp 160,000 per day, three times what farmers earn.

“Most young people are image-conscious. Most of them are afraid of getting dirty,” said Tisna Rohmat, a 33-year-old farmer. “They want to work in offices instead.

Cahyono Kurnia, a farmer from Ciwidey, West Java, said price uncertainties that lead to losses had discouraged young people from joining the sector and had forced some farmers to stop farming until they could raise enough capital to start again.

“Farmers must deal with harvest cycles. Some get their capital back, some do not,” said Cahyono, who now sells his tomatoes directly to consumers with the assistance of agritech start-up TaniHub Group.

Future of farming depends on investment

Tisna Rohmat, 33 years old, spoke of his vision for the future of farming during The Jakarta Post’s visit to his family farm in Ciwidey, West Java.

Seeing this family of passionate farmers, while rare, shed light on what could be the future of Indonesia’s agriculture sector, if Tisna’s peers followed his lead.

“If you want more young people to farm, you must show them our success stories, surely people will come around, and they will learn what farming is like. So we have to show farming to young people and invite young people to share and have a chat,” said Tisna, beaming with hope.

“There is no job where you can exert as much effort as farming. In farming, the potential is limitless. It all depends on what our capabilities are and how we use our intelligence.”

But for all Tisna’s passion, he needs support. Investment in agriculture must come from individuals, the private sector to the government and NGOs, people involved in the sector say. In a nutshell, it takes a village to sow the seeds for the future of agriculture.

“Increased investment in agriculture to modernize food systems and markets and make them more efficient is key to breaking this vicious cycle,” the Asian Development Bank (ADB) wrote in its 2019 report Policies to support investment requirements of Indonesia’s food and agriculture development during 2020-2045.

“Such investments will not only help improve the country’s food production but will also enable households to engage in more productive sectors and earn better incomes.”

Infrastructure investments in rural roads, electricity, cell phone towers, markets, cold chains and processing facilities should be expanded in partnership with the private sector, the crucial element to this effort, the report states.

The government’s increased investment in expanding irrigation and improving existing systems will increase crop yields and area, while promoting the adoption of advanced technologies, it adds.

Technology to break down barriers, reshape agriculture

Some technology-based companies are bridging the yawning gap between farmers and consumers. The likes of TaniHub and Sayurbox allow consumers to buy fresh produce directly from farmers.

Beyond that, TaniHub’s peer-to-peer lending arm TaniFund allows individuals to lend money to farmers so they can have a source of funds to expand their operations. TaniFund has channeled Rp 82 billion in loans to 1,500 borrowers since its founding in 2017.

Cahyono Kurnia, a 36 years old farmer from Ciwidey, West Java, is a TaniFund borrower who decided to focus on tomato farming to improve his yields. In his 16 years in farming, Cahyono has tried beans, potatoes, spring onions, cabbages — you name it.

Now with 1 hectare of land of his own and another hectare he rents, he feels more confident about his produce, also thanks to TaniHub’s tutor system that allows its field specialists to monitor farmers’ progress.

“Before TaniFund was available, I was hesitant to sell my harvests. I had doubts, as I wasn’t able to estimate my earnings from my crops because prices were unclear. Now, prices have been stable, and I can earn money from good prices,” said Cahyono, a father of two.

Agricultural technology startup Habibi Garden chief executive officer, Irsan Rajamin, said the utilization of internet of things (IoT) technology could be a magnet for millennials and youth to bring them into the agriculture industry.

“Millennials cannot take their eyes off of their phones, even for just an hour, so we just have to make their habits more productive,” he said.

Habibi Garden uses digital platforms and IoT to help farmers. By connecting sensors and irrigation systems in farms to the internet and providing data based on machine learning, Habibi Garden can help farmers monitor and maintain their farms and crops remotely.

Meanwhile, the Indonesia Japan Horticulture Public-Private Partnership Project (IJHOP4) uses blockchain technology to connect farmers with loans and insurance.

In partnership with data exchange platform HARA and local lender BTPN, the government-to-government initiative aims to improve farmers’ financial access and cultivation techniques, optimize local supply chains and facilitate links with modern markets.

“If demands can be met, it will improve the social and economic conditions of thousands of farmers,” said Setia Irawan, the CEO of farmers’ cooperative-cum-Islamic boarding school Al Ittifaq, a beneficiary of the Indonesia-Japan partnership.

Demand for the Japanese kuroda carrot variety alone from Al Ittifaq can reach 5 tons per week throughout the year.

Al Ittifaq empowers Islamic boarding school students to cultivate dozens of agricultural product types on its 14 hectares of land in Ciwidey, West Java, an area famous for its ecotourism that is two hours’ drive from Bandung city center.

‘Extraordinary challenge’ but hopes high — Government

Agriculture Minister Syahrul Yasin Limpo knows well that encouraging young people can be an “extraordinary challenge”. But the NasDem party politician has pledged to support young farmers by expanding access to innovations and funding schemes.

In its COVID-19 response, Rp 1.85 trillion from the Agriculture Ministry’s Rp 14.06 trillion budget for 2020 has been reallocated for seed assistance, labor-intensive programs, stabilization of food stocks and prices as well as food distribution and transportation.

The minister said the ministry would continue to develop district-based agricultural counseling centers under the Kostratani scheme to better respond to the needs of farmers, in addition to providing microloans to farmers and seeking to triple agricultural exports.

“I am optimistic that the agriculture sector will thrive and young people today will seize the opportunity. They are a generation that is good at capturing opportunities,” said the minister, a former governor of South Sulawesi.