A dedicated website in India hosts almost 50 posters and infographics, answers to frequently asked questions.PHOTOS: INDSCICOV.IN via The Straits Times/Asia News Network

BANGALORE — Try as she might, Ms Harita Raval could not find a Gujarati word for “soap lipid”. She was making a poster on how hand washing helps to reduce Covid-19 transmission. She knew soap was “saboo” in Gujarati, but what was lipid?

“Finally, I transliterated ‘lipid’ in Gujarati and added a definition in simple words at the bottom of the poster,” said Ms Raval, a science educator in Mumbai’s Homi Bhabha Centre for Science Education, based in the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research.

The center that usually trains teachers in mathematics and science has for the past three months been abuzz with making Covid-19 more comprehensible to laypeople.

India has 22 official languages, and people speak more than 19,500 dialects across the country. But nearly all academic scientific material is in English.

This disparity is more pronounced today, as governments and health workers try to demystify the coronavirus to 1.3 billion polyglot Indians.

Ms Raval has helped coordinate a team of scientists and researchers from 14 institutes who are creating multilingual resources for Indians to better understand the pandemic.

On their website, they have podcasts, almost 50 posters and infographics, answers to frequently asked questions, and short videos in 12 languages.

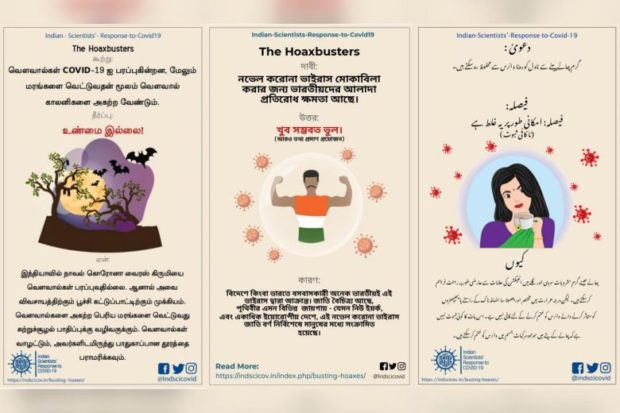

The broadest effort, however, comes from the Indian Scientists’ Response to Covid-19 (ISRC), a group of over 700 scientists, researchers and engineers across the country. The task force also includes translators, hoax busters, designers and illustrators who work in 19 languages including Konkani, Tamil, Malayalam, Hindi, Bengali, Assamese, Urdu and Meitei.

As rumours and superstitions about the pandemic spread through social media and even mainstream news channels, scientists and public health experts felt that access to trustworthy information in the mother tongue was essential.

“Facts and evidence can’t remain locked up in English, even if that may be the language of medicine and research,” said Ms Spoorthy Raman, a science communicator and former engineer who helped coordinate translations for the ISRC. She translated material to Kannada, a language spoken in the southern state of Karnataka.

“In English, the pandemic might feel far away, but in your mother tongue, it comes home, and you will take the dangers more seriously,” she added.

Creating accurate and accessible Covid-19 information for millions of Indians has been a fascinating challenge, say the scientists.

“Accurate scientific words don’t always mean much to people. Instead of going for a perfect translation, we would go for simple words used in day to day life,” said Mr Soham Jagtap, a doctorate student in Bangalore’s National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences who helped make Marathi content.

Social distancing is better explained in the local language as “two arms length” or “six feet distance”, but many Indians are used to words like virus and quarantine today.

In a Kannada webinar with scientists, Ms Raman noticed that non English-speaking attendees were more comfortable with the word “immunity” than the Kannada term “roga nirodhaka Shakti”.

For the over 660 million Hindi speakers in the country, this was less prevalent. “People used to say ‘rog’ or disease for epidemics. But after the Prime Minister used the exact Hindi words ‘mahamari’ for pandemic and ‘lakshan’ for symptoms in his speeches, people understand that,” said Ms Pratibha Singh, a health worker in Madhya Pradesh who used the scientists’ material to educate villagers.

Communicating the science in another Indian language often means thinking of whole communities that the anglophone world often forgets.

“When we did videos on how to wash hands for 20 seconds, we used the World Health Organisation guidelines but had to remember that not everyone in India has running tap water. Many use wells or ponds. We also created to-do lists catering to people in poor city neighborhoods who didn’t know how to isolate themselves in one-room houses,” said Ms Raman.

Hoaxes and superstitions can be region-specific too.

Mr Anand Subramanian, a brain disorders research scholar from Coimbatore who translated material into Tamil, said many in Tamil Nadu thought splashing turmeric water sanitized their houses.

“I don’t think residents in any other states believe this, except maybe some parts of the south,” he said. The ISRC issued clarifications that turmeric water does not help.

To disseminate the material widely, the scientists have used social media and coordinated with grassroots organizations, relief workers and teachers’ associations. ISRC created language-specific WhatsApp groups with science educators, teachers, rationalists and doctors to both share material and crowdsource emerging questions.

The more well-entrenched the group, the better it knows its community.

Bharat Gyan Vigyan Samiti, a mass literacy movement that operates in 23 states, translated material in Manipur and Nagaland, where each tribe has a different language.

The Tamil Nadu Science Forum created new vocabularies for social workers and for government messages.

Scientists, linguists and educators are almost all translating, writing and busting myths for no payment.

“The pandemic has shown us how central multilingual communication is for public health. I hope some of this will become more institutionalized,” said Ms Raval.