SUMMER RETREAT Condominiums, hotels and commercial buildings have sprouted in Baguio City after the 1990 earthquake but many of its residents and officials are working to keep development in check to preserve the charm of the country’s summer capital. —EV ESPIRITU

BAGUIO CITY—Fifty-four seconds were all it took for 28 buildings and 130 houses to topple or crack beyond repair in this city as a 7.8-magnitude earthquake hit Luzon mainland at 4:26 p.m. on July 16, 1990.

More than a thousand people died in this city, which was isolated for days when the temblor severely damaged main roads. Hunger, thirst and panic described Baguio’s first 48 hours.

In Dagupan City, 75 kilometers away, coastal sections dropped suddenly. The quake triggered liquefaction (subsidence of water-saturated soil) that caused 90 buildings to sink by a meter and collapse along the stretch. Seventeen people were killed and more than 60 injured.

The quake’s epicenter was traced near Cabanatuan City in Nueva Ecija province, where a massive jolt shattered the six-story building of Christian College of the Philippines (CCP) that trapped hundreds of students. Records showed 154 residents died, some from dehydration while awaiting rescue.

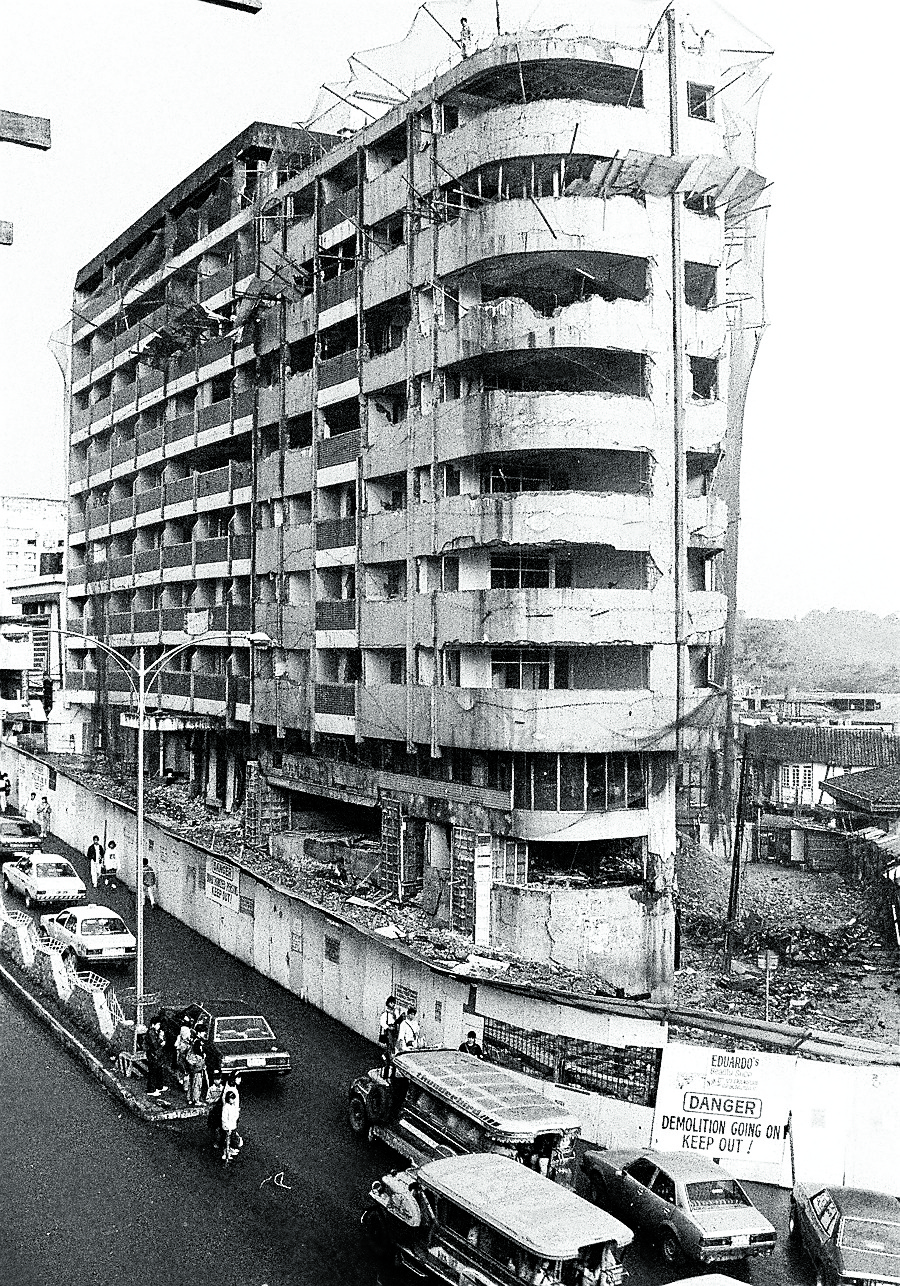

‘UKAY’ SPOT Skyworld Condominium on Session Road was condemned and demolished months after the July 16, 1990 earthquake rocked Baguio.—PHOTO BY EV ESPIRITU

The site where Skyworld once stood has become popular to tourists as an “ukay-ukay” (used clothes) center. —PHOTO BY EV ESPIRITU

Ill-prepared

That tragedy spawned more stories of heartbreak. but it was also the story of recovery, which could be a template for how cities and towns would rise from the coronavirus pandemic.In a newspaper column, the late Baguio journalist Jose Nicolas Ilagan said the earthquake revealed how “inadequate and ill-prepared we were to face nature’s unpredictable wrath … [displayed] the weakness of man-made structures, [and] exposed the cowards and opportunists.”

But the disaster “became the opportunity for testing and demonstrating the heightened social consciousness [of residents and civic leaders],” he said.

“In the face of government inadequacy and ineffectiveness, individuals and organizational initiative and service came to the fore,” Ilagan added.

Repairs were undertaken immediately in Baguio, Dagupan and Cabanatuan, spearheaded by the national government and the private sector, although it took three years for substantial repairs to be completed in Baguio and Dagupan.

Baguio’s civic leaders and nongovernment organizations drew up their version of an urban plan.

DAGUPAN SINKS, RISES Vehicles cruising along Perez Boulevard in Dagupan City (left) were stuck on road cracks after a 7.8-magnitude earthquake rocked Luzon on July 16, 1990. —PHOTO REPRODUCTION FROM THE COLLECTION OF JCI DAGUPAN INC. AND WILLIE LOMIBAO

Lockdown

The Luzon lockdown in March created some of the problems confronted by Dagupan residents 30 years ago, according to Mayor Brian Lim.

Lim, a first-time mayor, said his father, the late Mayor Benjamin Lim, was a young businessman when the quake destroyed the family-owned Magic Supermarket and Department Store that opened in 1989.

“[My father] suffered a minor heart attack during the quake, but he was unaware until the doctor told him. We also found out that he was diabetic,” the younger Lim said.

Days after the calamity, Dagupan looked “unrepairable,” he said. “Even my parents, who were devastated, planned to leave and settle in the United States,” he said, until their employees surfaced and offered to help rebuild.

Downtown Dagupan is busy, with traces of damage wrought by the quake gone. —PHOTO REPRODUCTION FROM THE COLLECTION OF JCI DAGUPAN INC. AND WILLIE LOMIBAO

‘Unsinkable’

Lim’s father banded together a group of businessmen and leaders of nongovernment organizations to rally residents behind Dagupan’s revival. They put up signs which read, “Dagupan is unsinkable. To sink is unthinkable. To leave is impossible. To rebuild we shall forever do.”

He convinced the reconstruction team to give priority to the rehabilitation of the public market, the core of city commerce.

“In 1990, there was no internet and so the public impression at the time was Dagupan had died and would not recover,” the younger Lim said.

Counseling services

The killer quake damaged many buildings, but CCP in Cabanatuan drew most of the attention because of the 20 dead there. Like Dagupan, local businesses immediately started rehabilitation efforts.

But traumatized CCP victims required “critical incident stress debriefing” which was essential for Cabanatuan’s recovery, said Dr. Eliseo Guerrero, who undertook counseling services when he was vice president of Araullo University based in the city.

Among his wards were students who were either trapped in the rubble or witnessed the tragedy, he said.

Businesses involved in the reconstruction followed strict building regulations to ensure no more structures would fall in case of another temblor, said architect Jun Dawang, who designed a new school building.

Malacañang’s account of the quake highlighted a young man, Robin Garcia, who survived the CCP building collapse but who returned to rescue his classmates. Garcia was killed on his fourth attempt when a portion of the building caved in.

Organizing food aid

The first two days of isolation in Baguio were spent organizing food and water distribution, while first responders from Benguet Corp. and cadets from the Philippine Military Academy helped volunteers crawl through fallen buildings to search for survivors.

“We do not know how much it actually cost to bring back Baguio,” said Antonio Tabin, a city accountant, because billions of pesos used to revive Baguio came from various donors here and abroad.

The city needed P50 million to rebuild its water system, and another P2 million to repair its reservoir at nearby Mt. Sto. Tomas.

The national government allotted P10 billion for reconstructing damaged communities.Barely a year later in June 1991, Mt. Pinatubo, a dormant volcano for 611 years, roared to life in one of the world’s most destructive eruptions in the 20th century. Thousands of people were killed while communities in Central Luzon were buried in subsequent lahar flows.Controversies

Despite the calamity, Baguio officials still dealt with controversies, beginning with businessmen who insisted on repairing condemned buildings.

Fake news also became a problem, and residents urged then Mayor Jaime Bugnosen to set up a “rumor control center.”

“What planners and authorities knew but were not saying was that the earthquake also opened the opportunity for the rise of graft and corruption … With the elections set for 1992, the war cheating activities of our unscrupulous politicians had actually begun,” Ilagan said.

The first Baguio structure to be rebuilt was a school building of Brent School in November, or four months after the quake. Brent was aided by the Episcopal Church Relief Center.

The Baguio Flower Festival was developed in 1995 to draw back people who had fled the city. —REPORTS FROM YOLANDA SOTELO, ARMAND GALANG AND VINCENT CABREZA