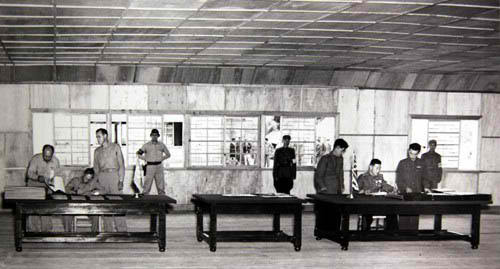

US and North Korea sign the armistice ending the three year Korean War in July 1953. Yonhap via The Korea Herald/Asia News Network

Thursday marks the 70th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. Now, military tension is still palpable on the Korean Peninsula, seven decades on.

Last week, Pyongyang demolished a liaison office that stood as a symbol of improved inter-Korean ties, worrying many here that several years of progress toward detente could so quickly be undone.

While a big question mark hangs over the direction the two Koreas are heading now, one thing history shows is that relations between the two have had their ups and downs, swinging between armed clashes and steps toward rapprochement.

“Inter-Korean relations is a continuation of advancement, retreat, achievement and setback,” said Lim Dong-won, a former director of national intelligence and unification minister during the Kim Dae-jung administration (1998-2003).

Here is a brief overview of events that have shaped the dynamics of inter-Korean relations from the war up until today.

Enemy states (1953-1969)

The brutal war, which killed more than 3 million people, came to a halt in 1953 when an armistice agreement was signed, but it was never replaced with a formal peace treaty. The years after the war were marked by deep tensions and enmity between the South and the North. The two Koreas were vying for legitimacy and international recognition. Tensions on the peninsula escalated in the late 1960s, with both sides attempting infiltration of one another and plotting coups.

A series of military clashes took place from 1966 through 1969, largely between North Korean and South Korean forces or between the North and US troops in the Demilitarized Zone. It was during this time, in 1968, that the North sent 31 commandos to sneak into Cheong Wa Dae in a failed attempt to assassinate President Park Chung-hee. That same year, the North also seized US spy ship the USS Pueblo and held 83 American crew members hostage for months.

Seesawing between detente and confrontation (1970-1987)

The thaw in the Cold War between the US and Soviet Union brought a mood of dialogue to the Korean Peninsula. In August 1971, the first Red Cross talks took place, with delegates from both sides meeting in Pyongyang to discuss humanitarian issues and reunions of separated families.

The following year, after secret dialogue between the South Korean intelligence chief and North Korean leader Kim Il-sung, the two Koreas issued their first joint statement: the July 4 South-North Joint Communique. They agreed that reunification should be negotiated peacefully and without foreign interference. Under the agreement, the two Koreas established their first “hotline.”

But the 1980s were a dark decade, with Pyongyang detonating a bomb in Myanmar in 1983 aimed at top visiting South officials, killing 21 people. South Korean President Chun Doo-hwan narrowly escaped. In 1987, another bombing killed all 115 passengers on Korean Air Flight 858. Pyongyang officially denied involvement in either attack.

Progress toward peace (1988-1997)

After Seoul hosted the Summer Olympics in 1988, the South pushed to broaden its diplomatic frontier, normalizing relations with China, the former Soviet Union and Eastern European bloc countries. As part of this policy, President Roh Tae-woo also reached out to North Korea, and after many rounds of dialogue the two sides signed a nonaggression pact vowing freer trade, travel and cultural exchanges. The two Koreas also joined the United Nations in 1991. In 1992, the two Koreas agreed not to test, possess, produce or use nuclear weapons and to renounce uranium enrichment and plutonium reprocessing.

The agreement did not last long, as North Korea threatened to go nuclear, pushing the peninsula to the brink of war. But the nuclear crisis was defused when former US President Jimmy Carter visited Pyongyang and brokered what could have been the first-ever summit between the two Koreas since the war ended.

In a dramatic turn of events, Kim Il-sung died in July 1994, two weeks before the summit was to take place, and his son Kim Jong-il took the helm of the regime. Later that year, North Korea signed a major nuclear deal, agreeing to dismantle its nuclear facilities. Over the next several years, inter-Korean relations turned volatile, with issues including food aid and a North Korean submarine infiltration incident in 1996.

Sunshine era (1998-2007)

Kim Dae-jung, who became president of South Korea in 1998, introduced the “Sunshine Policy” of engaging North Korea with massive shipments of aid, investment and trade to encourage the reclusive regime to open up. In 2000, the first-ever inter-Korean summit took place between Kim Dae-jung and the North’s Kim Jong-il in Pyongyang.

The highly anticipated meeting culminated in the adoption of the June 15 South-North Joint Declaration, in which both sides pledged to work together for peace and unification. Later that year, Kim Dae-jung won the Nobel Peace Prize, a first for the country.

The Sunshine Policy continued, despite the two Koreas facing off in naval clashes in the West Sea in June 2002. Meanwhile, the US took a hard-line stance on North Korea, with US President George W. Bush calling the North part of an “axis of evil.” The following year, the North withdrew from the Nonproliferation Treaty.

Despite the North expanding its nuclear weapons program, the South stuck to the engagement policy under liberal President Roh Moo-hyun (2003-2008). The first round of six-party talks involving China, the US, the two Koreas, Japan and Russia, aimed at ending the North’s nuclear program through negotiations, was convened in 2003.

In 2006, the North conducted its first nuclear weapons test, leading the UN to impose sanctions against it.

With international sentiment toward Pyongyang worsening, Seoul felt the need for an inter-Korean summit. The following year Roh went to Pyongyang for the second inter-Korean summit, and in a joint statement both sides vowed mutual efforts to resolve the nuclear issue on the Korean Peninsula.

Back to a hard line (2008-2017)

Things took a dramatic turn under new conservative President Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013), who from the start demanded that the North give up its nuclear weapons.

In July 2008, a North Korean soldier shot dead a South Korean tourist at Mount Kumgang, and as a result the tourism program was suspended. In 2010, the North’s attack on South Korean naval vessel Cheonan resulted in the death of 46 South Korean sailors. Pyongyang denied involvement, but Lee announced unilateral sanctions. Months later, North Korea fired artillery shells on a South Korean border island, killing four people.

In 2011, Kim Jong-un took power in the North following the death of his father, Kim Jong-il.

Under the conservative Park Geun-hye administration (2013-2017), inter-Korean relations remained tense. The North’s young leader pursued the “Byungjin” policy — simultaneously seeking nuclear development and economic growth — and pushed ahead with nuclear weapons and ballistic programs. The North conducted its third nuclear test just days before Park assumed office in February 2013, with the fourth and fifth rounds in 2016, during her presidency.

Park imposed additional sanctions and suspended all commercial exchanges and joint projects. Kaesong industrial park was closed in 2016 in response to the North’s nuclear tests.

Moon as facilitator (2017-present)

Moon Jae-in was sworn into office in May 2017 in South Korea partially on a pledge to improve inter-Korean ties, aligning with the stance taken by former liberal Presidents Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moon-hyun.

Amid an escalating war of words between US President Donald Trump and Kim Jong-un, Moon managed to broker a cease-fire the following year by inviting North Korean delegates to the PyeongChang Winter Olympics. The Olympic truce eventually led to three inter-Korean summits between Moon and Kim, and also to the historic Singapore summit between Trump and Kim, which marked the first-ever meeting between the leaders of the US and North Korea. This was all in 2018.

Hopes were running high ahead of the second US-North Korea summit in February 2019. Peace on the Korean Peninsula, and its complete denuclearization, felt imminent. But the Hanoi summit fell through despite much fanfare, as Trump and Kim failed to narrow their differences over the steps the sides needed to take toward denuclearization and sanctions relief.

The US-North Korea denuclearization talks came to a deadlock, and so did inter-Korean relations. In an effort to break the impasse, Moon called for various cross-border projects to engage Pyongyang, but the North did not respond to any of Seoul’s proposals.

Recently, Pyongyang suddenly began building tensions again, demolishing the inter-Korean liaison office and warning further hostile actions against the South.