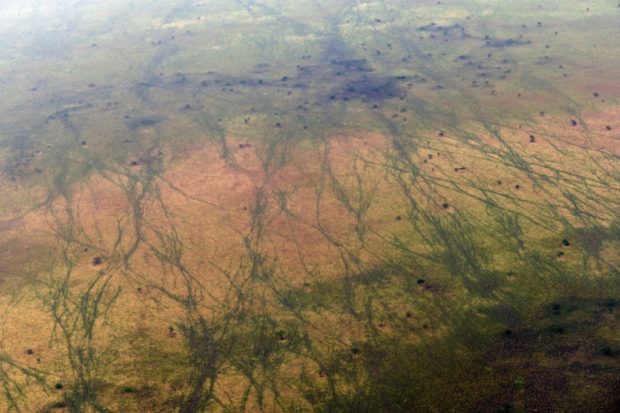

A aerial view of intertwining hoof-paths in the ground by migrating antelope across the landscape between Boma and Badingilo national parks, covering an estimated area of 37,500 km2 is seen on February 4, 2020. South Sudan holds enormous ecotourism potential, boasting Africa’s largest savanna and wetland, the second-largest mammal migration on earth, and the lions, elephants and myriad other endangered and iconic species that have long lured visitors to the continent. Photo by TONY KARUMBA / AFP

BOMA, South Sudan — The light plane banked sharply to circle back over the plains. The pilot had spotted something below: antelope, first one, then many, the stragglers of a million-strong migration across this vast wilderness.

But there are other wonders out here on the savanna. A trio of extremely rare Nubian giraffe lumber by, the seldom-seen, majestic giants casting long shadows over the grasslands.

“There’s only a few hundred left in the world,” said Albert Schenk, of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), surveying the landscape below.

“So you’re seeing something spectacular,” he added.

This is South Sudan: one of Africa’s wildlife Edens, a global biodiversity hotspot wedged between the continent’s tropical jungles and dry, desolate deserts.

But it’s almost never seen by outsiders.

Ruinous civil wars have left South Sudan with few paved roads or airstrips. It is the size of France but huge swathes are isolated or impenetrable.

These are some of the least-explored, and most remarkable, wild habitats in Africa.

Against the odds

A general view of Boma National Park in eastern South Sudan on February 4, 2020. South Sudan holds enormous ecotourism potential, boasting Africa’s largest savanna and wetland, the second-largest mammal migration on earth, and the lions, elephants and myriad other endangered and iconic species that have long lured visitors to the continent. Photo by TONY KARUMBA / AFP

South Sudan boasts Africa’s biggest wetland, the Sudd, and its largest intact savanna, a stretch of untouched wilderness east of the White Nile that reaches all the way to Ethiopia.

Every year, some 1.2 million antelopes and gazelles cross this enormous ecosystem — at 95,000 square kilometers (37,000 square miles), it is the size of Hungary.

The mega-herds leave miles-long scars in the grasslands, clearly visible from the sky.

In scale and scope, the migration is rivaled only by the fabled wildebeest crossing in the Mara and Serengeti.

But South Sudan is also custodian to hardy populations of lions, elephants and countless other endangered species that survived — against all odds — decades of war and near-decimation by poachers.

Vanishing species

“There are still wild animals in South Sudan,” said former wildlife minister Alfred Akwoch Omoli, the shelf behind him decorated with miniatures of elephants and giraffes.

“It may be the envy of other countries that we have such animals.”

This natural heritage, however, is under constant threat, and wildlife conservation, where it is done at all, is difficult and dangerous.

Researchers and rangers contend with rebel militias and well-armed poachers in remote, often lawless terrain where government control is weak.

Some 15 percent of the country is national parks and reserves, land in theory protected by law, but overseen by an underfunded wildlife department stretched too thin to police its realm.

On the day an AFP team visited Boma National Park, before the coronavirus pandemic, rangers unfurled two leopard skins seized from a local man who caught the endangered cats in a snare.

“There used to be plenty of wildlife here, living close to the community,” William Til, the acting park warden in Boma, deep in the country’s eastern interior, told AFP.

“Before the war people would use dogs, or spears, and just catch a few animals, and were satisfied with that. But now with automatic rifles, it’s become harder for wildlife. Bigger species have vanished from the area.”

In the decades-long war for liberation from Sudan, zebras and rhinos, once abundant in the southern region that became the new nation of South Sudan in 2011, were hunted to extinction.

Antelope and giraffe were slaughtered to feed soldiers on all sides.

Elephants — numbering some 80,000, 50 years ago — were wholesale massacred for ivory to fund the fighting.

Their numbers are reduced to an estimated 2,000 today.

Sights on safari

A conservationist assesses the carcas of a male white-eared Kob for signs of poaching for game meat, a rampant practice among rural communities, at the Boma National Park in eastern South Sudan on February 4, 2020. South Sudan holds enormous ecotourism potential, boasting Africa’s largest savanna and wetland, the second-largest mammal migration on earth, and the lions, elephants and myriad other endangered and iconic species that have long lured visitors to the continent. Photo by TONY KARUMBA / AFP

Protecting the country’s wildlife isn’t a burning priority for the fragile state, which only this year formally ended a six-year civil war that killed close to 400,000 people.

However the government is aware of the benefits it could bring.

South Sudan’s tattered economy is hinged on oil and any other ways of generating jobs and revenue — such as conservation management or ecotourism — will be critical in future, Omoli said.

“What does it (the wildlife) do? It brings tourists… They will pay the money, and the money will be used for development,” Omoli, who was replaced in February when South Sudan formed a new coalition government, told AFP.

South Sudan takes inspiration from neighbors like Uganda and Rwanda.

Also convulsed by past conflict, today they are safe and popular destinations for tourists and their holiday money.

A viable tourism sector could take years, even decades, to develop and would require significant outside investment, likely to be scarce given the impact that the coronavirus has wreaked on the global economy.

Conflict conservation

Schenk said that maintaining peace and security, which has so far eluded South Sudan in its short and troubled history, was critical to wildlife and habitat protection.

Years of conservation and community work at Boma National Park derailed in 2013 when fighting erupted between government and rebel forces, turning the savanna into a battlefield.

The rangers deserted, and the park warden was executed.

“Our compound was completely looted,” said Schenk, of the field site WCS established in Boma in 2008 to spearhead their program.

“The only thing left was the concrete slabs on which we had our safari tents. We had to build it all up again.”

But a peace deal was signed in September 2018, halting armed combat, and aerial surveys and camera traps revealed all was not lost.

The wildlife endured, hiding out in mighty swamps and dense bushland, just as during past conflicts.

And the great columns of antelope and gazelle that first put South Sudan on the global conservation map continued their circular movements.

Cause for hope

The country’s wild reaches keep throwing up surprises, too, buoying optimism for the future.

In recent years, rare and elusive species like bongos, painted dogs and red colobus monkeys have been photographed by conservation group Fauna and Flora International, inviting speculation about what else lurks in this underexplored land.

“There’s a hell of a lot more out there than we know yet,” said Schenk.

Last year, the US government donated $7.6 million to a three-year program to protect wildlife and spur economic opportunities in the Boma-Bandingilo landscape, including through ecotourism.

WCS has also co-drafted legislation to expand protection to the migratory corridor between Boma and Bandingilo national parks — critical given oil and mineral claims in the area, and “pressure” to open habitats to exploration, Schenk said.

Til, patrolling on foot in his fatigues, clings to hope that conservation will one day “help in bringing development” to this remote corner of South Sudan, where lions growl in the darkness.

“We’re not giving up,” he said.

A yellow-billed kite accosts a hooded vulture from below in a tussle over territory at the Boma National Park in eastern South Sudan on February 4, 2020. South Sudan holds enormous ecotourism potential, boasting Africa’s largest savanna and wetland, the second-largest mammal migration on earth, and the lions, elephants and myriad other endangered and iconic species that have long lured visitors to the continent. Photo by TONY KARUMBA / AFP