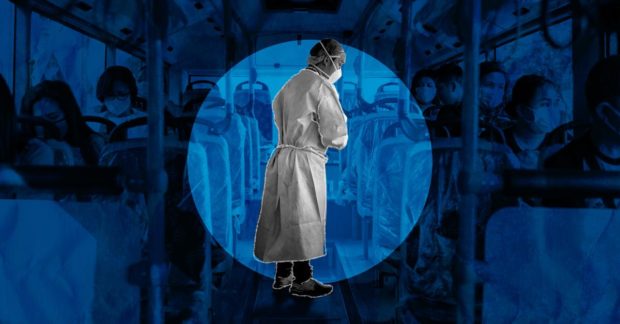

Alarming reports of attacks and discrimination against Filipino health workers and those on the frontlines came to light after Luzon and other areas were placed under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ) in mid-March to stop the transmission of SARS Cov2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

Last March 27, a staffer of St. Louis Hospital in Tacurong City, Sultan Kudarat province, was mobbed by five individuals who splattered bleach on his face as he was on his way to work.

On the same day, a male nurse from Cebu City was on his way home from work when he was splashed with chlorine by unidentified men on board a motorcycle.

In Lucena City, Quezon province, an ambulance driver was shot and wounded on March 31 after a subdivision resident castigated him for parking his vehicle inside the village.

In early April, two nurses from Cebu City were barred from entering a condominium unit where they were staying as guests of the unit owner, a friend based in France. The nurses said they were refused entry after the condominium management learned they were nurses. The management has since denied the discrimination and said it was just a case of “miscommunication” borne by strict protocol and guidelines on guests.

But it doesn’t end here. As health workers continue to be at the forefront of the battle against COVID-19, the stigma and discrimination against them persist. According to the Joint Task Force COVID Shield, there have been at least 104 incidents of recorded attacks against front-line health workers as of May 1. Meanwhile, the number of infected health workers in the Philippines has risen to 2,314 as of May 17, 1,341 of which are considered active cases. Thirty-five have also died.

Stigma and discrimination

Stigma is the negative regard or perception toward a specific group of people due to a particular attribute, according to social psychologist Dr. Marshaley Baquiano, an associate professor at the University of the Philippines Visayas and a member of the Psychological Association of the Philippines.

Discrimination, on the other hand, pertained to negative acts or treatment toward stigmatized groups. These can include rejection and avoidance of the stigmatized group or individual, subjecting them to threats and violence, and using degrading or dehumanizing language against them.

Stigmatization is common during disease outbreaks, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This has been palpable during the COVID-19 pandemic and has cut across different groups of people, with those on the frontline, health workers, COVID-19 patients, persons under investigation and those of Asian descent experiencing stigma and discrimination because of their association with the disease.

“Perhaps one of the things we have to remember here is that stigmatization [and] discrimination have grave consequences, especially for the stigmatized groups or stigmatized individuals,” said Dr. Baquiano. “These consequences could be long-lasting [and] accumulate across time. These could be pervasive.”

Baquiano narrated the effects of discrimination, saying these have the capacity to hurt both a person’s physical and mental health.

“I could be more stressed, I could be more anxious and there is always the sense of being excluded,” she said.

“Studies also show that [for] those who are discriminated against, it is possible they would underperform because of the stress, anxiety. Or it could be because they’re discriminated against, they may have low self-esteem, so they won’t be able to perform well,” Baquiano added.

She said that the relationships of a group or person being discriminated against could also suffer, leading them to withdraw or isolate themselves from their social groups.

Even more, some may feel scared of being discriminated against over COVID-19 that they may not seek health care should they actually get sick.

Baquiano also said she had been thinking of the possibility of a triple or multiple jeopardy, wherein the different factors in a person’s identity magnify or multiply the effects of discrimination based on social class, gender, physical abilities or age, among others.

“I was thinking of triple jeopardy. [For example] I contracted the disease, then I am also a woman, I am also poor, and a PWD (person with disability) — the discrimination could be so much worse,” she said. “Why? Because of the intersectionality.”

Sources of discrimination

But why do people discriminate? Baquiano said there are complex factors that cause people to discriminate against a certain group or individual, in this case health workers.

There are cognitive sources of discrimination, she said, one of which is prejudice which may develop out of a person’s “rational evaluation” of danger presented by critical groups.

“For example, in this case, health workers are exposed to the disease, so people’s rational evaluation is that since they are exposed, they may have contracted the [disease],” she said as an example. “So, if I am near them, I could also contract it, so the tendency is to protect myself, I avoid them.”

Another cognitive source of discrimination is the natural tendency to categorize other people, which involved labeling and the separation of an “us” and “them”.

There are motivational sources, too, according to Baquiano, which could compel a person to look for someone they can exclude when motivated by fear or frustration. There is also the power of social force, like socialization, for example children learning prejudice from what they see from their parents.

“The greater the identification with the parents, the stronger the socialization of prejudice,” she explained.

“What else? Control learning from our neighbors. Neighbors can pass on prejudice, peers can pass on prejudice, and remember, sometimes we want to conform because we want to belong,” she said.

“So, even if we don’t really think that way, we agree with discriminative behaviors [and] prejudices because we do not want to be the ones who are excluded or discriminated,” she added.

Institutional support is also a social force of discrimination, leaving room to ponder whether certain policies in place actually reinforce discrimination and prejudice against certain groups of people.

The media, along with films and television programs, can also be sources of discrimination when these present stigmatized groups in a negative light.

Language matters

“Think before you speak” is an age-old proverb that is often repeated enough, yet seems easier said than actually done. But words can have the power to normalize and reinforce discrimination — and can have grave consequences if left unchecked.

“Be mindful or be alert of the language and words we use that border on social or moral exclusion, just remember always that words or labels matter a lot,” advised Baquiano.

For example, the word “victim” is often thrown around in the face of calamity or disaster, but Baquiano suggests using the term “survivor” instead because it does not take away the sense of agency, or their capacity to act independently and make their own choices, of those being discriminated against.

The same goes with referring to someone as “suspected” or “suspect case” of COVID-19 since there are other terms that are less discriminating, such as “person presumed to have COVID-19.”

“Among social psychologists, we avoid using the term panic because it’s counterproductive,” she added.

“If you say people are panic buying, people would think that there’s something to panic about, so all the more they would panic buy, so the word panic should not be used as much as possible. Let’s be careful with the words we use.”

People may sometimes use the same words over and over again, so much so that these become automatic and unconscious, but these can also contribute to the normalization of discriminative language and structural violence. One can be complicit without being aware of it and so, mindfulness cannot be stressed enough.

“Since these are the words that are always used, you think it’s okay, and then it has become part of the cultural narrative and later on, it could result to structural violence,” Baquiano said.

“So, unconsciously, we are not aware that because of these discriminatory narratives about certain groups of people, we end up contributing to structural violence, so we have to be careful.”

Combating discrimination

There is more to be done to combat discrimination beyond being mindful of one’s words and thoughts, however.

According to Baquiano, it is important for people to give the right information and spread facts, as well as promote in everyday conversations and interactions social norms that discourage discriminatory and prejudiced behavior.

“We should correct stigmatizing languages. Not because you hear someone say something [discriminatory], you just end up laughing,” she said. “You become part of that normalization, it becomes structural violence.”

What else? Baquiano believes that if people are in the position, they can advocate for or advocate with stigmatized groups and bring their voices to policymakers. Local government units, too, should also think of proactive ways to come up with policies that would protect people who are being discriminated against, she said.

Many LGUs have indeed issued local ordinances seeking to penalize those who would discriminate against people found positive for COVID-19, persons under monitoring and investigation and health workers. These include the local governments of Manila, Quezon City, Pasig City, Angeles City, Pasay City and Las Piñas, among others.

Coping with fear

When it comes to coping with one’s own fears and anxieties in the middle of the pandemic, Baquiano said that it is helpful to be armed with the right information.

One should practice self-care by making sure they have good hygiene and a healthy and balanced diet.

“I don’t believe in social distancing, I believe in physical distancing,” she added.

“I keep myself socially connected with people not necessarily face-to-face but through online chat, through calls,” she said. “We make sure we are safe because we don’t have a medical vaccine yet, so physically distancing would help us a lot.”

Keeping calm is also important, since one could be overwhelmed by all the news about COVID-19.

Baquiano also recommended seeking professional help for those who may feel overwhelmed during the pandemic. “If you think you need that, then don’t be scared to ask for help from a professional,” she said.

Lastly, she believes extending help to others can also help oneself.

“How do we help others? Maybe we can remember the three Ls, the psychological first aid,” she said.

“Look, check for safety basically, then distress reactions in others. And then listen. Listening, meaning approaching those who need support and listening to their concern and [helping] them keep calm,” she added.

“The third L would be link because I cannot handle everything on my own. So, what I can do is link this person with a professional, link this person with [the Department of Social Welfare and Development], link this person with an LGU, so I should give the right information.”

With reports from: Niña Guno, Ador Vincent Mayol, Edwin Fernandez, Delfin T. Mallari Jr., Dale Israel, Delta Dyrecka Letigio, Melvin Gascon, Katrina Hallare, Consuelo Marquez, Tonette Orejas, Gabriel Pabico Lalu, Daphne Galvez