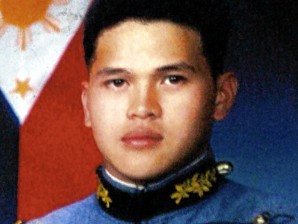

NEW EVIDENCE The Office of the Ombudsman reversed itself and filed charges against 10 Navy officers in the Sandiganbayan Wednesday for the murder of Navy Ensign Philip Pestaño 16 years ago.

Agreeing with the parents of Navy Ensign Philip Pestaño that he did not kill himself 16 years ago, the Office of the Ombudsman reversed itself and filed murder charges against 10 Navy officers in the Sandiganbayan Wednesday and ordered their dismissal for grave misconduct.

If they could no longer be dismissed, the alternative penalty is a fine equivalent to their one year salary.

The 24-year-old Pestaño was found dead in his cabin aboard the BRP Bacolod City on

Sept. 27, 1995, shortly before the ship was to dock at the Philippine Navy headquarters in Manila. He had bullet wounds in the head.

A supposed suicide note was found on his body, but his parents, Felipe and Evelyn, refused to believe that their son killed himself and filed charges against the Navy officials.

In 2009, the antigraft body, then headed by Ombudsman Merceditas Gutierrez, dismissed the complaint, saying the evidence was circumstantial.

The Pestaños filed a motion for reconsideration, which was granted in an order approved by Gutierrez’s successor, Conchita Carpio Morales, on January 10.

The alleged inaction on the Pestaño case was one of the grounds raised against Gutierrez during her impeachment last 2011.

Charged with the nonbailable crime of murder were Capt. Ricardo Ordoñez; Cmdr. Reynaldo Lopez, Hospital Man 2 Welmenio Aquino, Lt. Cmdr. Luidegar Casis, Lt. Cmdr. Alfrederick Alba, Machinery Repairman 2 Sandy Miranda, Lt. Cmdr. Joselito Colico, Lt. Cmdr. Ruben Roque, PO1 Carlito Amoroso and PO2 Leonor Igcasan.

Circumstances

In the latest order, Ombudsman Morales said the circumstances surrounding the young officer’s death belied the earlier finding that he had committed suicide. His own wounds did not appear self-inflicted, she said.

Morales said Pestaño had two contusions on the right temple and a cut in the left ear, which, it added could not have been caused by the bullet fired into his head but a hard, blunt object.

The bullet’s entry wound was oval in shape and did not bear any tattooing, smudging or burn mark as what would have happened during a close-contact fire, Morales said.

“It is farfetched for a person who commits suicide to shoot himself in the head at a distance,” she noted.

Citing findings of forensic experts, the Ombudsman said the handwriting on the suicide note was different from that of Pestaño’s.

Bullet path

The conflicting observations on the trajectory of the bullet also debunked the suicide theory, Morales said.

While the autopsy report showed a downward trajectory, the Philippine National Police Crime Laboratory said the bullet mark on the cabin wall was caused by a bullet hurtling upward.

The bullet was also found on the bed and not on the floor where it should have landed, the Ombudsman said.

Morales further pointed out a blood smear was found on the cabin wall, but no blood spatters, bone fragments or human tissue on that wall despite its close proximity to the bullet’s exit point.

The Ombudsman cited the finding of splotches of blood on the pillow parallel to Pestaño’s head, as well as pools of blood on the bed. As a forensic expert said, the blood could not have crawled up from the bed to the pillow.

Morales found it hard to give credence to Aquino’s testimony that Pestaño borrowed his gun to kill himself. Pestaño had his own gun in the first place, it said, and it was “irrational” for an officer and a gentleman who wanted to die by his own hands to borrow a gun.

Gangway duty

Aquino could also not have been at the gangway that time since he assumed his gangway duty only after Pestaño was found dead, the Ombudsman added.

In finding the 10 Navy officers liable for the death, Morales said it appeared that their apprehension that Pestaño would expose the illegal activity aboard the Bacolod City motivated them to kill him.

She noted that the Senate and Armed Forces received information about a shipment of undocumented lumber aboard the ship in exchange for drums of fuel oil.

Pestaño, as cargo deck officer, was said to have objected to the shipment but was prevailed upon by the superior officers to allow it.

Unnatural reactions

The Ombudsman said the officers’ reaction to finding Pestaño dead was unnatural.

Morales said Ordoñez did not rush to see Pestaño but instead focused on docking the ship at the Navy headquarters. He should have seen to it that the pieces of evidence in the cabin was not moved, she added.

Lopez, who claimed to be Pestaño’s closest friend, did not immediately go to the cabin, Morales said, but waited for the ship to dock and for the police to arrive. This is not a normal reaction for someone losing a friend to suicide, she added.

The Ombudsman said Colico, who found the body, did not immediately report it to the executive officer or check on Pestaño’s breathing or pulse. She said the normal reaction of a fellow officer would have been to check if the victim was still alive.

Casis did not stop Colico from picking up the gun, emptying it of bullets and cleaning it with a piece of paper, Morales said. She said Casis, a graduate of the US Naval Academy, would not have been ignorant of basic protocol in crime investigations.

The individual reactions “run counter to the grain of human nature and experience” and led the Ombudsman to conclude that they had conspired to kill Pestaño and to fabricate evidence to make it appear as a suicide.

Conflicting statements

The officers also gave conflicting statements, Morales said.

At first, Colico told the National Bureau of Investigation that Roque had told him to check on Pestaño, but he later told police officers that he took it upon himself to look in on his colleague, Morales said. He also gave different times when asked when he found the body.

Colico said that when he cleaned the gun and removed the bullets, he was with Casis and Aquino. But Alba said he, Miranda and Aquino were the ones present. Roque claimed to have been at the scene, but this was contradicted by Casis.

Ordoñez failed to disclose the presence of Amoroso on the ship when Pestaño died, the Ombudsman said.

Ordoñez later said Amoroso disembarked at Sangley Point in Cavite and never returned.

But Amoroso’s cabin mates said he was on board the ship on its trip to Roxas Boulevard where the Navy headquarters is located.

‘Unusual dogleg route’

The Ombudsman gave weight to new evidence presented by Pestaño’s parents, which came from the Armed Forces investigation and made available to them only 10 years after their son’s death.

One such evidence was the ship’s “unusual dogleg route” from Sangley to the Navy headquarters. The trip usually takes 45 minutes, but it took two hours on the day of Pestaño’s death.

“An unexplained delay of about one hour and 15 minutes raises the presumption that the prolonged trip was occasioned by the time it took respondents to create the suicide scenario,” the Ombudsman said.

Pages were also ripped off from the gangway logbook, which would have shown the names of the crew members aboard the ship.

There was also no passenger manifest that would have shown who was on board at that time. This could have been the basis as to who would have to undergo a paraffin test to see if any of them had fired a gun, the Ombudsman said.

These indicate an attempt to conceal important information, Morales said.

The Ombudsman’s order was signed by graft investigation and prosecution officer Yvette Marie Evaristo, Director Dennis Garcia, Assistant Ombudsman Eulogio Cecilio and Overall Deputy Ombudsman Orlando Casimiro.

Originally posted at 05:12 pm | Wednesday, January 11, 2012