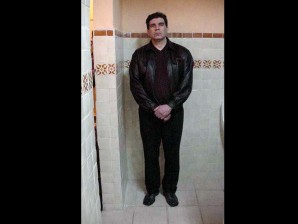

- In this March 9, 2002 file photo released by Mexico's Attorney General's Office, Benjamin Arellano Felix stands in his home the day of his arrest in Puebla, Mexico. Arellano Felix will plead guilty to unspecified charges, the U.S. attorney's office in San Diego said Wednesday, Jan. 4, 2012. Spokeswoman Debra Hartman said she could not elaborate in advance of the filing. Arellano Felix is expected in federal court Wednesday afternoon. Arellano Felix headed a once-mighty cartel that came to power in Tijuana, Mexico, in the late 1980s. (AP Photo)

SAN DIEGO — Mexican drug cartel kingpin Benjamin Arellano Felix pleaded guilty Wednesday to racketeering and conspiracy to launder money, avoiding the spectacle of a trial for one of the world’s most powerful drug lords of the 1990s.

Under an agreement with federal prosecutors, Arellano Felix, 58, can be sentenced to no more than 25 years in prison — a lighter punishment than ordered for many lower-ranking members of his once-mighty, Tijuana-based cartel.

Prosecutors also agreed to dismiss other charges that could have brought 140 years in prison if he was convicted.

Arellano Felix could be released from U.S. prison in 20 years if credited for time served in this country and good behavior, assuming he gets the maximum 25-year sentence, said his attorney, Anthony Colombo Jr.,

As a Mexican citizen, he would then be deported to Mexico, where he still has nine years left on a sentence for related crimes.

Arellano Felix acknowledged during a hearing in U.S, District Court that he led an organization that distributed hundreds of tons of cocaine and marijuana in the United States and raked in hundreds of millions of dollars in proceeds that were sent back to Mexico, sometimes inside cars.

He acknowledged the organization bribed law enforcement officials and killed rivals.

Colombo said the government may have agreed to the deal to avoid having to bargain with 21 potential government witnesses for reduced sentences in exchange for their testimony. They also may have wanted to avoid a lengthy trial.

“They have to consider years and years of litigation, plus the expense, is avoided by this resolution,” Colombo told reporters.

Prosecutors declined to answer questions from reporters.

Arellano Felix stood attentively during the hearing, acknowledging his guilt as U.S. District Judge Larry Burns recited parts of a 17-page plea agreement. The judge scheduled sentencing for April 2.

Arellano Felix told the judge that he has been suffering migraine headaches almost daily but that they didn’t impair his judgment to accept the plea agreement

John Kirby, a former federal prosecutor who co-wrote the 2003 indictment against Arellano Felix, said the case rested entirely on cooperating witnesses, instead of wiretaps or physical evidence. He said those cases weaken over time as witnesses die, get into more trouble or change their minds about testifying.

“This kind of case is based solely on witness testimony, and it slowly disintegrates,” Kirby said. “Maybe from the time when we put it together and now, it’s not such a great case anymore.”

The cost of a trial was unlikely to have influenced prosecutors, Kirby said.

“The government doesn’t care about the expense, the government cares about winning,” he said.

Francisco Javier Arellano Felix, a younger brother who led the cartel after Benjamin was arrested in Mexico in 2002, was sentenced in San Diego to life in prison in 2007, a year after he was captured by U.S. authorities in international waters off Mexico’s Baja California coast. Jesus Labra Aviles, a lieutenant under Benjamin Arellano Felix, was sentenced in San Diego to 40 years in prison in 2010.

Benjamin Arellano Felix was extradited from Mexico in April 2011 to face drug, money-laundering and racketeering charges. He is one of the highest-profile kingpins to face prosecution in the United States.

The U.S. indictment said Arellano Felix was the top leader of a cartel he led with his brothers, going back to 1986. It says the cartel tortured and killed rivals in the United States and Mexico as it smuggled Mexican marijuana and Colombian cocaine.

“He was the top of the chain,” Kirby said. “The brothers were at the top, and he was at the very top. He had the final say … He was like the CEO of the operation.”

The cartel, which was known to dissolve the bodies of its enemies in vats of lye, began to lose influence along California’s border with Mexico after Arellano Felix was arrested in 2002. A month earlier, his brother, Ramon, called the cartel’s top enforcer, died in a shootout with Mexican authorities.

Benjamin Arellano Felix was incarcerated in Mexico after his 2002 arrest and was later sentenced to 22 years in prison on drug trafficking and organized crime charges.

Arellano Felix also agreed to forfeit $100 million, a figure that will be difficult for the government to collect.

“Whether there is anything out there that (the government) can seize, I don’t know,” Colombo said.