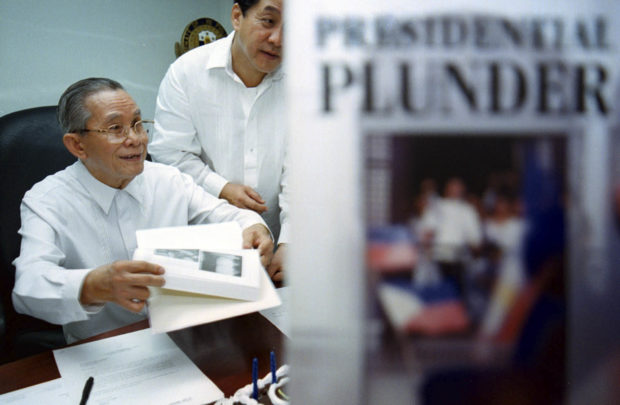

PLUNDER BOOK Former Senate President Jovito Salonga, who first headed the Presidential Commission on Good Government, signs copies of his book “Presidential Plunder: The Quest for the Marcos Ill-Gotten Wealth” at its launching in 2000. In his book, Salonga says the briefcase that was stolen in New York contained only photocopies of documents and belonged to another PCGG official. —LYN RILLON

MANILA, Philippines — How could it happen that the Sandiganbayan would dismiss three ill-gotten wealth cases against the Marcoses and their cronies due to insufficient evidence when government prosecutors are supposed to have expansive public resources at their disposal?

Three cases filed against the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, his wife Imelda and their cronies in the period immediately after the February 1986 Edsa uprising were dismissed in three consecutive months this year because government prosecutors had submitted photocopies instead of original documents.

The antigraft court in its separate decisions also cited other insufficiencies committed by those tasked with proving the defendants guilty.

In his column in the Inquirer on Nov. 24, former Chief Justice Artemio V. Panganiban said he was convinced that “the fault lies squarely with the Office of the Solicitor General (OSG) and the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG).”

But Solicitor General Jose Calida, head of the agency representing the government in litigation procedures, blames the late former Senate President Jovito Salonga, first chair of the PCGG, for the adverse rulings.

Stolen briefcase

In a chance interview after a Senate hearing in November, Calida said government lawyers were forced to present duplicates because Salonga lost a briefcase containing documents that could pin down the Marcoses and their cronies to a snatcher in a Korean restaurant in New York in March 1986.

Salonga died in 2016. In his book “Presidential Plunder: The Quest for the Marcos Ill-Gotten Wealth”published in 2000, he said the stolen briefcase belonged to another PCGG official and contained only duplicates of crucial papers.

And in a 1998 letter addressed to then Inquirer columnist Belinda Cunanan, Salonga said he witnessed how the original papers that would incriminate the Marcoses were stored in a vault of the Central Bank, now the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas.

The three ill-gotten wealth cases languished in the Sandiganbayan for more than 30 years.

Six presidents have come and gone since the PCGG was formed in 1986. It has survived on an average of P116.782 million in annual allocation from the government, according to its acting chair, Reynold Munsayac.

Benedicto et al.

In August, the Sandiganbayan’s Second Division dismissed a P102-billion forfeiture case against the Marcos couple and cronies led by Roberto S. Benedicto, filed on July 31, 1987.

The PCGG had accused Benedicto of exploiting his connections to the Marcoses to secure hundreds of millions of pesos in loans and guarantees for his businesses, including bulk carriers that handled freight contracts for sugar, fertilizer and other import cargoes.

But the antigraft court said the PCGG “miserably failed to adduce evidence” to hold the Marcos couple liable.

“It saddens the court that it took more than 30 years before this case is submitted for decision and yet, the prosecution failed to present sufficient evidence to sustain any of the causes of action,”it said.

It also said the PCGG had provided only photocopies of documents that could have connected the transactions to the Marcos couple, including a resolution by the Development Bank of the Philippines’ board of governors approving a $32.7-million loan favoring Benedicto’s companies.

“In civil cases, the party making allegations has the burden of proving them by a preponderance of evidence. In addition, the parties must rely on the strength of their own evidence, not upon the weakness of the defense offered by their opponent,” the court said.

Marcos dummies

In September, the same branch dismissed the P1.052-billion civil case the PCGG filed in March 1988 against former ambassador Bienvenido Tantoco, some of his relatives, and Dominador Santiago for supposedly acting as dummies of the Marcoses in acquiring artworks, jewelry, real estate and stakes in businesses at the height of the dictatorship.

The court cited “insufficiency of evidence,”saying that documents and witnesses presented by state prosecutors had failed to prove conspiracy between the Marcoses and the Tantocos.

It said the government “failed to prove by preponderance of evidence,”as required in civil cases handled by the PCGG. Other documentary evidence offered were also rejected for being “mere photocopies,” a violation of the Best Evidence Rule (or Rule 130, Section 3 of the Rules of Court, which states that no evidence is admissible other than the original document itself).

The court also noted the “unjustified non-appearance of government lawyers” and that the PCGG presented only four witnesses.

And in a resolution dated Nov. 20, it rejected the motion for reconsideration filed by the PCGG, saying “no new argument was presented” by the plaintiff.

‘Mere photocopies’

In October, the Sandiganbayan’s Fourth Division cited “defects” in the evidence presented by the PCGG and the OSG in the P267.37-million ill-gotten wealth case against the Marcoses and associates Fe and Ignacio Gimenez filed on July 21, 1987.

The court chided the two agencies for submitting “mere photocopies”with no “substantive probative value”and “unauthenticated private documents.”

It also said “no explanation was offered by the [OSG] as to why the original copies of these exhibits were not presented.”Again, it accused the PCGG of violating the Best Evidence Rule.

But Calida told the Inquirer that the Best Evidence Rule made the situation difficult for state prosecutors.

An appointee of President Rodrigo Duterte, Calida also pointed out that while OSG lawyers were tasked by Executive Order (EO) No. 1 signed by President Corazon Aquino with acting as prosecutors in cases against the Marcoses and their associates, he was not yet the Solicitor General when the three cases were filed.

18 cases still pending

He was dismissive when asked if it was possible for the OSG to remedy the situation. There are still about 18 PCGG cases against the Marcoses pending in the Sandiganbayan, per the Senate committee onjustice and human rights.

Calida said the cases were old cases and that many documents were lost during Salonga’s term as PCGG chair and the PCGG was left with duplicates: “Matagal na ’yung mga kasong ’yun. And then the documents were lost a long time ago. They were lost noong time nila Salonga. Marami daw, marami. Originals ang nawala, kaya nga Xerox copies na lang naiwan. Saan yung Xerox copy kinuha? Sa original, di ba? [The PCGG and OSG] cannot produce the originals. What can we do?”

Calida said the 18 pending cases against the Marcoses and their associates also relied on photocopied evidence.

“Blame the PCGG. The previous [one], not [the one] now,”he said, adding that while PCGG lawyers were tasked with getting evidence against the Marcoses, the OSG and its lawyers “are not the repository of documents.”

On the other hand, PCGG acting chair Munsayac remains optimistic that the government can rely on the “admissibility of secondary evidence, like photocopies, as exception”to the Best Evidence Rule when the Sandiganbayan decides on the 18 pending cases.

Preponderance of evidence

Responding to an email inquiry sent after the court’s Second Division said its piece on preponderance of evidence, Munsayac cited the same principle as indicated in EO 14-A signed by President Corazon Aquino on Aug. 18, 1986.

He cited Section 3 of the order, which states that “civil suits to recover unlawfully acquired property filed with the Sandiganbayan against Marcos, Imelda, members of their immediate family, close relatives, subordinates, close and/or business associates, dummies, agents and nominees, may proceed independently of any criminal proceedings and may be proved by a preponderance of evidence.”

Munsayac also maintained that the current PCGG had no hand in the submission of photocopies by earlier batches of officials.

“First of all, the public must be informed that no single document or evidence was lost during the tenure of the current PCGG administration. In fact, the cases recently decided by the Sandiganbayan were all filed and litigated by the past administrations, [with] some already submitted for decision as early as 2010,” he said.

He added: “Simply put, the insinuations that the present officers of PCGG and OSG should be blamed for those cases are not only unfair, they [also] defy logic.”

But Munsayac stressed that when government prosecutors submitted photocopies during previous administrations, it did not mean “the government is in possession of the originals and they just chose to submit photocopies.”

Defendants’ possession

“Most of the time, the government can only acquire photocopies of certain documents from witnesses as the originals are in the possession of the principal defendants themselves,”he said.

Anyone with ill-gotten wealth who places an asset under the name of a dummy or other representative “would normally retain all original documents of title or transfer as they tend to incriminate him,”Munsayac said. “Do we really think the principals in illegal transactions would turn over those original documents to the government so they can be used against them?”

He played down concerns that Calida’s close ties with the Marcoses could hamper PCGG efforts to recover more ill-gotten assets.

“Contrary to unfair insinuations, every government agency involved in the prosecution of PCGG cases is exerting all effort to advance the Republic’s claims. We are all aware that the interest of the Filipino people is more important than any personal relationship or political inclination,” he said in his email.