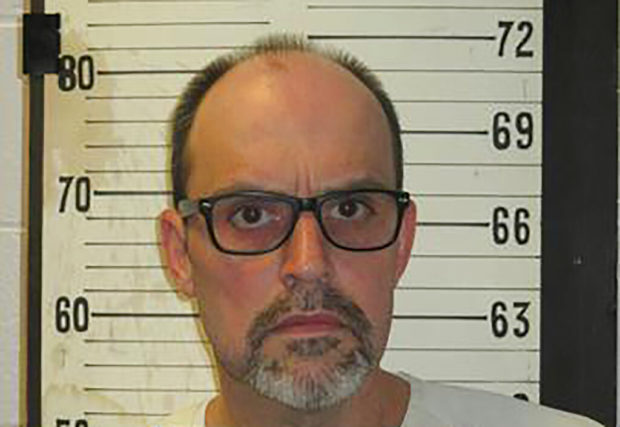

This 2017 file photo provided by the Tennessee Department of Correction shows Lee Hall, formerly known as Leroy Hall Jr. Hall, a death row inmate. Hall was electrocuted Thursday, Dec. 5, 2019. Hall walked onto death row nearly three decades ago with his sight, but attorneys for the 53-year-old prisoner say he’s since become functionally blind due to improperly treated glaucoma. AP.

NASHVILLE, Tenn. — A blind prisoner convicted of killing his estranged girlfriend by setting her on fire in her car was put to death Thursday in Tennessee’s electric chair, becoming only the second inmate without sight to be executed in the U.S. since the reinstatement of the nation’s death penalty in 1976.

Lee Hall, 53, was pronounced dead at 7:26 p.m. at a Nashville maximum-security prison, corrections officials said. He chose the electric chair over Tennessee’s preferred execution method of lethal injection — an option allowed inmates in the state who were convicted of crimes before January 1999. He also became the first blind inmate in U.S. modern history to die by electrocution.

Hall was already strapped into the electric chair when the curtains were raised for the witnesses — which included family, attorneys and reporters.

As his head swiveled around the room not appearing to focus on anything, he was asked if he had any final words. Hall initially said he needed a glass of water before talking. He was denied and asked again to make a statement.

“People can learn forgiveness and love and will make this world a better place,” Hall said, wearing a white T-shirt and rolled-up white pants.

Hall received two jolts of electricity while in the chair. During the first 20-second burst, his right pinkie became hyper-extended before it slumped and his body collapsed. During both jolts, a small plume of white smoke appeared above the right side of his head.

A spokeswoman for Tennessee Department of Correction later told The Associated Press that it “was steam and not smoke as a result of the liquid and heat.”

No media witnesses have reported seeing steam or smoke during the previous three electrocutions since the state began resuming executions in August 2018.

Hall had his vision when he entered death row decades ago, but his attorneys say he later became functionally blind from improperly treated glaucoma. Only one other known blind inmate has been executed in the U.S. since the Supreme Court allowed executions to resume in 1976.

Court documents state that Hall killed Traci Crozier, 22, on April 17, 1991 by setting her car ablaze with a container of gasoline that he lit and tossed in her vehicle while she was inside and trying to leave him. The container exploded and Crozier suffered burns across more than 90% of her body, dying the next day in the hospital.

Crozier’s sister, Staci Wooten, and her father, Gene Crozier, watched Hall’s execution.

“Hopefully today ending this monster’s life will bring some peace within everyone who has had to suffer throughout these 28 years without my beautiful sister,” Wooten said after the execution.

Defense attorney Kelly Gleason had asked the federal courts to stop Hall from being put to death after other attempts in state courts and with Tennessee’s governor had failed. Those attempts officially came to a halt less than hour before Hall’s execution when the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene.

Hall’s attorney John Spragens read a brief statement from Hall’s family. Hall’s brother, David, was in attendance with the media witnesses during the execution, as well as Hall’s spiritual adviser.

“We are devastated by the loss of Traci and now Lee,” the statement read. “Lee loved Traci more than anything and we welcomed her into our family and love her too. We also love Lee and wish that we could have changed the events of that tragic day.”

Hall’s attorneys had been fighting for months to delay the execution plan, arguing that courts should have had the opportunity to weigh new questions surrounding a possible biased juror who helped hand down the death sentence decades ago against Hall, who was formerly known as Leroy Hall Jr.

The woman — simply known as “Juror A” — acknowledged publicly for the first time this year that she failed to disclose during Hall’s jury selection process that she had been repeatedly raped and abused by her former husband. Hall’s attorneys argued the omission deprived him of a fair and impartial jury — a right protected in both the Tennessee and U.S. constitutions

However, both the Tennessee Supreme Court and Gov. Bill Lee declined to step in despite pleas from Hall’s attorneys for more time to explore the possible legal concerns.

Lee, a Republican, has not intervened in any of the four execution cases that have come across his desk since he became governor in January.

The Supreme Court has never ruled on whether use of the electric chair violates the 8th Amendment ban on cruel and unusual punishment, but it came close about 20 years ago after a series of botched electrocutions in Florida.

Meanwhile, state courts in Georgia and Nebraska have declared the electric chair unconstitutional.

The high court has also neither set an upper age limit for executions nor created an exception for a physical infirmity.

Tennessee is one of six states in which inmates can choose the electric chair, but it’s the only state that has used the chair in recent years. Four out of six recent inmates put to death in Tennessee have chosen the chair since the state began resuming executions in August 2018.