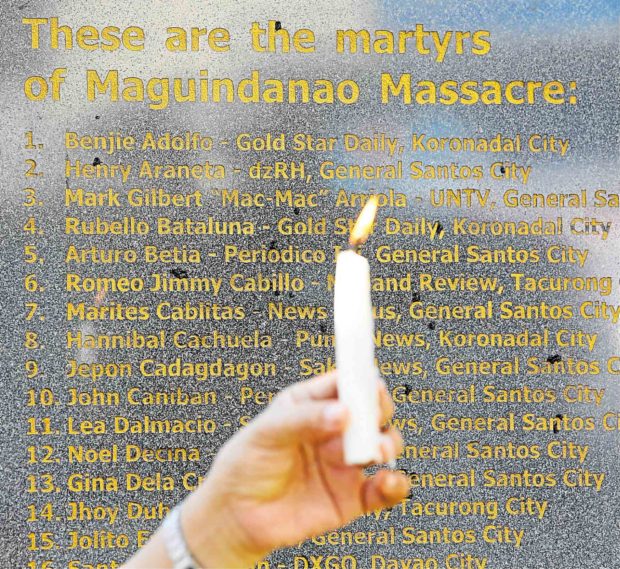

TRAGEDY FOR PH PRESS A marker at the National Press Club building in Manila pays tribute to the 58 victims of the 2009 Maguindanao massacre, remembering them as martyrs. —INQUIRER PHOTO

(Second of three parts)

Even after she and her family migrated to the United States in August 2012, Ma. Reynafe Momay Castillo carries on the fight for justice for her father, a media worker believed to have died in the Maguindanao massacre in 2009 but whose body was never found.

There were dentures, an identification card, other personal items, and testimony proving that her father, Reynaldo “Bebot” Momay, a 61-year-old part-time photojournalist who lived near Maguindanao, was part of the Mangudadatu convoy and was among those buried in Sitio Masalay.

“Ten years is a long time for a verdict to come especially when 58 people were killed,” said Castillo, who now works as a nurse in the United States. “A lot of children are now living miserable lives after losing their mothers and fathers who were breadwinners of the family. These kids have gone through a lot.”

Before she decided to leave the Philippines for good, Castillo had been actively attending the court proceedings through her lawyers at Center for International Law Manila (Centerlaw). She was also one of the most outspoken among the victims’ family members when it came to their quest for justice.

‘58th victim’

She fought for her dad, considered the “58th victim” of the Maguindanao massacre, to be included by the Department of Justice in the criminal complaint filed against the Ampatuans and their coaccused.

“It was a long fight, a very exhausting fight. But my lawyers from Centerlaw never left me,” she said in an exchange via Facebook Messenger.

The last time Castillo came home was when her mother died in June 2015. Although positive that Quezon City Regional Trial Court Judge Jocelyn Solis-Reyes would hand down a guilty verdict on the Ampatuans, she said she was not planning to return to the Philippines.

“I feel that I’ll never come back home. Both of my parents are gone. I just need to heal. I’m sure it will come to pass,” she said.

‘Snail-paced system’

With a trial that took almost a decade, Castillo admitted to have developed trust issues concerning the Philippine justice system.

“Our justice system is such a snail-paced system,” she said. “We got word that the verdict will come early this year, but it never happened.”

When Chief Justice Diosdado Peralta granted Judge Reyes’ request for 30 more days, or until Dec. 20, to come out with her decision on the case, even the victims’ lawyers were appalled.

“The victims have waited [for] 10 years. They can wait a further 30 days. But it is so wrong that it took this long,” said lawyer Harry Roque, who represented some of the victims’ families. “The Maguindanao massacre trial should trigger systemic changes in our justice system.”

Castillo is not the first immediate family member of the victims to leave their native land. Myrna Reblando, wife of slain Manila Bulletin reporter Bong Reblando, left the Philippines in July 2012 and sought political asylum in Hong Kong.

Others have found employment overseas to be able to sustain their families.

The victims’ families, as well as witnesses, have been struggling to live normal lives and make ends meet for themselves now that they are bereft of their socioeconomic networks, according to private prosecutor Nena Santos.

Bribery, threats, murder

Since the trial began in 2010, witnesses had also been bribed, threatened and even killed. Suwaib Upham, who had admitted to being one of the gunmen in the massacre and was the first witness that Centerlaw sought to protect, was murdered in June 14, 2010.

Upham returned to Maguindanao when he was refused admission into the Philippines’ witness protection program. He was gunned down by a lone attacker in Parang town, just days after the 2010 presidential election.

“After the promulgation, witnesses and victims’ families need to restore their normal lives. I hope they will receive financial and educational help,” Santos said.

For its part, the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP) has set up a scholarship program for the continuing education of the victims’ children.

“[The scholarship program] was crucial because most of the victims of the massacre were their families’ breadwinners,” said NUJP president Nonoy Espina. “Unfortunately, last year, our partners informed us that they could no longer continue funding the program.”

Impunity

Espina said the NUJP was still looking for potential partners to continue sending to school the orphaned children of victims of the Maguindanao massacre and also other media killings.

According to Espina, impunity persists in the Philippines because of the lack of accountability.

Since 1986, the NUJP has recorded 187 media killings in the country. “While cases have been filed over many of the incidents, there have been less than 20 convictions, almost all of gunmen, not of masterminds,” he lamented.

Espina said that while a guilty verdict in the Maguindanao massacre case “would most surely be welcome,” the fact that media killings were continuing even after a decade “shows that the struggle for genuine freedom of the press and of expression remains unwon.”

“Nevertheless, it is also heartening that the community of independent Filipino journalists has refused to concede the fight and continues striving to deliver the information people need to make decisions about their individual and collective futures,” he added.

As for Castillo, her faith in Philippine courts will only be restored when the government acts on its justice system.

“It has been torturous. We were traumatized by the incident but they’ve tortured us even more by making us wait for [justice] for a long time, even with very clear evidence,” she said.

(To be concluded)