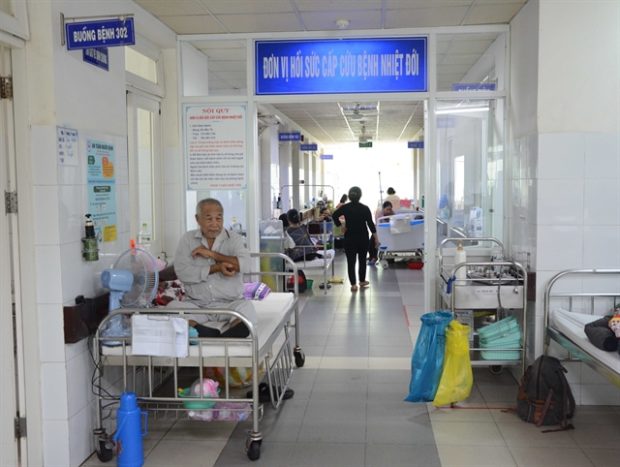

The rising number of dengue fever patients is overloading the Tropical Medicine Faculty at Đà Nẵng Hospital as the outbreak of the mosquito-borne disease in the central city has reached “alarming level”, according to the Đà Nẵng Disease Control Centre. VNA/VNS Photo Văn Dũng

HANOI — Dengue fever epidemics could be forecast up to eight months in advance by a new satellite-based, early warning system.

This system, known as D-MOSS, is being developed by a consortium led by HR Wallingford and sponsored by the United Kingdom Space Agency’s International Partnership Program.

D-MOSS is developing a forecasting system in which earth observation datasets are combined with weather forecasts to predict the likelihood of dengue epidemics.

The project, which started in Vietnam last year, aims to develop an operational early warning system to improve dengue prevention and increase control capacity.

It creates better understanding of the relationships between environmental stressors, the hydrological-climate system and human health.

The project also estimates the likelihood and severity of future dengue outbreaks under a range of climate change scenarios up to 2100.

According to Dang Quang Tan, deputy head of the Preventive Medicine General Department, dengue fever caused global losses of about US$9 billion annually.

In Vietnam, the disease placed a huge burden on preventive healthcare service due to high rates of infection and deaths, Tan said.

“Since 2000, the number of dengue fever cases increased by 100 per cent. In 2017, the country had a serious outbreak with 17,000 infected cases and 38 deaths,” Tan said at a workshop reviewing the project co-held on Monday by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the World Health Organization (WHO) and Vietnam’s Ministry of Health (MoH).

“The information shared by countries contributed to coping with the borderless dengue fever epidemic in the region in the context of climate change,” he said.

Speaking at the workshop, the UNDP Deputy Resident Representative Sitara Syed said: “As climate was changing rapidly, dengue would tend to change dramatically as it is highly sensitive to temperature, humidity and rainfall.”

“Water availability directly impacted dengue epidemics due to mosquito breeding sites. However, water availability or water resource management was rarely accounted for in dengue prediction models,” she said.

The fight against dengue required cooperation among countries and regions to ensure the best information, experiences and creative tools were shared in time, she said.

For any country, existing tools needed to be supplemented with innovative ones to help control and minimise the disease spread, she added.

Representatives of Cambodia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka attended the workshop to share experiences of their fights against the disease.

On Monday, the MoH also held a meeting on preventive measures for the winter-spring epidemic.

Winter and spring is a favourable time for many infectious diseases to develop, said Dang Quang Tan, deputy head of the Preventive Medicine General Department.

“The epidemics would spread easily and widely if there are no drastic preventive measures,” Tan warned.

The common infectious diseases in the season are flu, measles, pertussis, swine streptococcus, acute diarrhoea, avian flu, dengue fever, foot and mouth disease, rubella, encephalitis and diphtheria.

Notably, as of this month, there were more than 250,000 cases of dengue fever, tripling the same period last year, causing 49 deaths.

The main reason for the increase of infectious diseases in winter and spring was due to prolonged humid weather and increase of poultry product consumption.

The low rate of vaccination, especially in remote areas, also worsened the spread of disease.

Doctor Tran Minh Dien, deputy head of the Central Paediatrics Hospital, said that the hospital had received many children infected with measles.

The unvaccinated patients suffered serious complications, the doctor said.

Therefore, many solutions had been proposed such as strict and effective surveillance of the diseases, timely detection and prevention, and increasing the vaccination rates, Tan said.