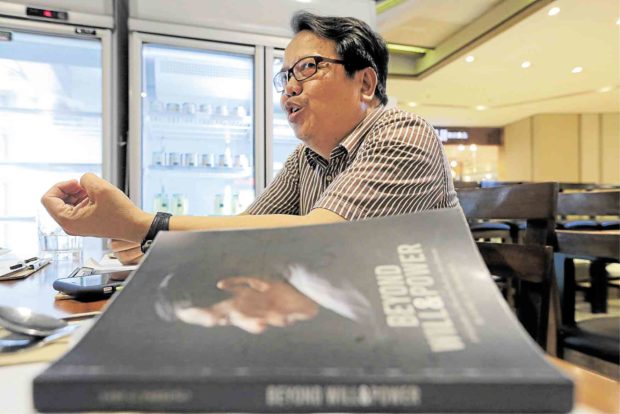

FOR THE READERS TO DECIDE In an Inquirer interview, Earl talks about his recently launched book, “Beyond Will and Power,” a biography of President Duterte. —GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

MANILA, Philippines — President Rodrigo Duterte has always spoken proudly of his “Moro lineage” and the “Maranao bloodline” of his maternal ancestors.

“Ang lola ko, Maranaw (my grandmother is Maranao)” is a standard line in his speeches. His official Wikipedia page describes his mother, the late Soledad Duterte, as “a civic leader of Maranao descent” without citing its source.

And yet, according to writer and political analyst Earl Parreño in his unauthorized biography of Mr. Duterte, the President is “a full-blooded Spanish-Cebuano with a bit of Chinese (racial stock).”

The book, “Beyond Will and Power” was launched and released in select bookstores in October.

Painstaking documentary research and dozens of interviews on the President’s ancestry led the writer to a number of startling and perplexing discoveries about the origins of the nation’s 16th leader.

Among his discoveries is that the President is not technically a Roa, but a Fernandez. His grandfather, Eleno Fernandez, had changed his last name to Roa upon being adopted by the clan during the latter’s search for his missing mother in Maasin town, Southern Leyte, at the turn of the 20th century.

Unanswered

Eleno’s mother might or might not be a Roa herself, but the identity of the President’s little-known great grandmother was left unanswered in Parreño’s chronicle of the Presidents’s family tree, although there are clues from which readers may draw their own conclusions.

What’s clear is that the President “could not possibly be descended” from a tribe of indigenous Moro people known as Maranao, even taking into account the presumed Roa side of his family, Parreño said.

“I didn’t find the need to explicitly state that he is not Maranao in my book,” the author said in an interview with the Inquirer on Monday.

But it remains a curious point: Why has the President’s claim stood unchallenged for so long?

In a September 2018 freedom-of-information inquiry, a graduate student requested the National Archives for documents pertaining to the “Maranao lineage or ancestry of President Duterte.” The request was denied.

But “why are you all so interested in this?” Parreño had asked when the Inquirer pressed him to elaborate on his discovery. He recalled talking to veteran Mindanao journalist Carolyn Arguillas who similarly asked: “Why didn’t you include one or two lines saying he’s not Maranao?”

Said Parreño: “In the first place, I don’t know if he’s just joking whenever he talks about being Maranao. For [22] years as mayor, he had never claimed to be Maranao, and now he suddenly is?”

“All I want is to present my findings without making any sort of judgment,” he added.

Multifaceted study

This detached, almost clinical approach, is reflected throughout Parreño’s exploration of Mr. Duterte’s life and persona in “Beyond Will and Power.”

In 227 pages, the book presents readers with a multifaceted study of the President—as a “frail and shy” boy who idolized his politician dad; a troublemaker who shot and wounded a fraternity brother during his college years; a ladies’ man who alienated his wife with his womanizing, and a public official whose political savvy and cunning grew over time.

The biography follows at least three generations of the Roa-Duterte family over a period of one and a half centuries. It delves into the roots they planted in various corners of the Visayas and Mindanao, weaves in his tumultuous youth and his early years as a lawyer and prosecutor, dives into his beginnings as a politician, and explores his ascent to the presidency.

First draft

In his introduction, Parreño takes pains to point out that his portrait of Mr. Duterte is neither meant to exonerate nor condemn him, though he does not shy away from painting the President’s character in broad strokes through scenes and vignettes from his past.

Upon reading the first draft of the book, former activist priest Edicio dela Torre, who wrote the preface, recalled asking Parreño “why he has not drawn explicit conclusions” from the voluminous materials he had gathered on Mr. Duterte’s life.

“He answered that he wants the readers to draw their own conclusions,” wrote Dela Torre, lauding the author for heeding Paulo Freire’s philosophy of avoiding interpretations in political education.

Explaining his choice, Parreño admitted that he had swung back and forth between an objective and subjective style. “But as I developed my research, the polarization only grew,” he said.

“I told myself: ‘So many people still don’t understand him.’ So ultimately, I felt that I didn’t need to add my subjective analysis; I only needed to present the facts,” he added.

Divisive figure

The President, Parreño noted, has become a divisive figure among Filipinos since winning the election in 2016. “It’s either you hate him or you love him. But there is a way to tell his story that is truthful and fair. You only need to narrate the facts. Facts establish truth,” he said.

After all, “you cannot twist anything about his ancestry; you cannot twist anything about his rise to power,” said Parreño, also the author of “Boss Danding,” an unauthorized biography of businessman and Marcos crony Eduardo Cojuangco Jr. that was published in 2003.

Unlike Cojuangco, Mr. Duterte proved to be a more elusive subject because of the dearth of available information. “When I did ‘Boss Danding,’ I had plenty of material to guide me, but here, nothing. Everywhere I searched, there was very little literature,” said the author who was not granted a face-to-face interview with the President.

In spite of his efforts at objectivity, Parreño acknowledged framing his narrative from philosophical vantage points by attempting to explain the President’s decisions and policies from his readings and most enduring influences.

Among them, Friedrich Nietzsche loomed large. The title of the book itself alludes to Nietzsche’s concept of the “will to power” as the primary driving force in humans, and indeed, in Mr. Duterte.

The President’s drug war is consistent with the German thinker’s idea of an imagined superior race called the “Übermensch” and its antithesis, the “last man,” in this case, the addicts, Parreño said.

“The will to power is not about overpowering weaker people, but overcoming his own weaknesses,” he added.

Political awakening

In terms of political strategy and leadership, the author said Mr. Duterte appeared to have been molded by the utilitarian perspectives of Niccolo Machiavelli’s “The Prince” and Sun Tzu’s “Art of War,” which he enjoyed discussing with close associates.

Such tomes are known to have inspired some of history’s despots and tyrants, raising the question: Is this kind of thinking dangerous in a leader of the modern age?

Parreño did not have a quick answer. “It’s not necessarily wrong to use Nietzschean philosophy or Machiavellian strategy, but it depends on how one wields power with these perspectives,” he said.

But while those thinkers might have influenced the President’s worldview, according to Parreño, there was perhaps no other person who had shaped his character as much as his late father, Vicente Gonzales Duterte.

The young Duterte’s political awakening occurred as he watched his father navigate the complexities of Davao politics and witnessed the betrayals that handed Vicente his congressional defeat in 1967. Three months after that election, in February 1968, the former Davao governor suffered a stroke and died, leaving his son stricken with grief.

Trust issue

Mr. Duterte was studying political science in college at the time. Thus, “Vicente never saw his son study law and pass the bar. He never saw him become a fiscal and then a politician. He never saw him rise to the presidency,” Parreño said.

This is tragic for a man who longed all his life for his father’s approval, the author said.

Dela Torre said it was reasonable to conclude that as a result of Mr. Duterte’s exposure to the “shifting coalitions, intense competitions and painful betrayals” experienced by his father, he “would find it difficult to trust other politicians to keep their word, or mean what they say.”

To that Parreño agreed.

“(Mr. Duterte) trusts no one,” he said.

Parreño said he hopes his book would help demystify Mr. Duterte and enlighten a populace that had remained largely ignorant about the man three years into his presidency.

The President’s partisans, according to the biographer, would do well to keep in check what historian Renato Constantino called “veneration without understanding” in his scathing essay that criticized the uninformed public adulation of Jose Rizal.

In similar fashion, Parreño wondered, “why do Duterte supporters venerate him if they do not understand him?”

As for Mr. Duterte’s critics and broader opposition forces, they, too, would benefit from examining the President’s life story, the author said, reminding them of one of Sun Tzu’s main tenets:

“Know your enemy.”