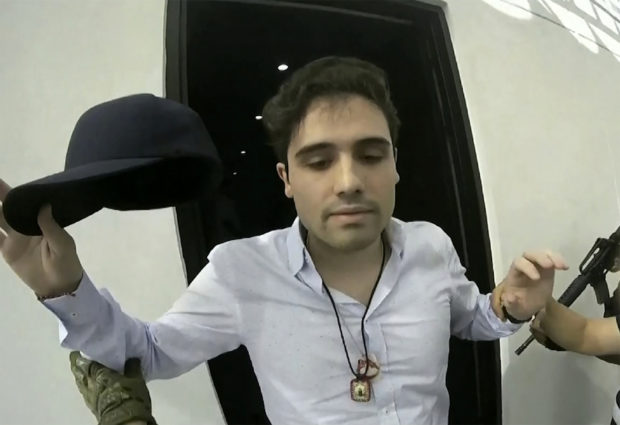

This Oct. 17, 2019 frame grab from video provided by the Mexican government shows Ovidio Guzman Lopez at the moment of his detention, in Culiacan, Mexico. Mexican security forces had Ovidio Guzman Lopez, a son of Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, outside a house on his knees against a wall before they were forced to back off and let him go as his gunmen shot up the western city of Culiacan. (CEPROPIE via AP)

MEXICO CITY — A sloppy operation that failed to nab Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s son followed by days of changing explanations has revealed not so much that Mexico has a failing security strategy, but no real strategy at all, experts have said.

President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and his security Cabinet have defined their strategy thus far by stating what it is not, according to experts, saying that Mexico is no longer waging a war on drugs or seeking to capture or kill cartel kingpins, like previous governments did.

But these words were apparently contradicted by the bungled October 17 mission to capture Ovidio Guzmán in the western city of Culiacan, the Sinaloa Cartel’s backyard, which aimed to nab a cartel figure and unleashed violence that made the city look like a war zone.

When asked to define what his strategy is to tame Mexico’s sky-high murder rate and deadly drug cartels, López Obrador responds with philosophies more than strategies, often mentioning an assortment of social programs.

On Thursday, López Obrador said his government will not be forced into a drug war, adding that his strategy is something else.

“Nothing has hurt Mexico more than the dishonesty of the governing,” Mexico’s president said, implying corruption was to blame for the country’s insecurity, violence, and drug trafficking.

He seemed to lay blame for the Culiacan operation with everyone except the drug traffickers, even lambasting the press for “yellow” journalism.

“This is pacifying the country by convincing, persuading without violence, offering well-being, alternative options, better living conditions, working conditions, strengthening values,” he said.

On the campaign trail, he summed this up with the catchy phrase: “abrazos, no balazos,” or “hugs, not bullets.”

But now he’s president, Mexico is on track to record more than 32,000 murders this year and the public just watched 13 people die in the streets of Culiacan while a special army antidrug unit captured and then released a drug lord to avoid further bloodshed.

“He can’t continue with this strategy of peace and love with the criminals and say that there isn’t war,” said Raúl Benítez, a security expert and professor at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

“The criminals are declaring war on the government and the country, the citizens, the people,” he added.

López Obrador also faced questions Thursday about uncharacteristically public grumbling from within the ranks of Mexico’s military. A Mexican newspaper this week published a speech by Gen. Carlos Gaytán to other military officers after the Culiacan debacle, which has followed a series of cartel attacks on Mexican security forces.

The retreat in the face of cartel gunmen reinforced the impression that the government has long ago relinquished effective control of whole towns, cities, and regions to the drug cartels.

“We’re worried about today’s Mexico,” Gaytán said. “We feel aggrieved as Mexicans and offended as soldiers.”

López Obrador brushed aside any concerns of a schism within military ranks, who he has favored with increased responsibilities and resources.

“I don’t have the slightest distrust of the army,” López Obrador said. “On the contrary, I have the support, the loyalty of the army.”

Experts said the climbing homicide numbers and the administration’s inability to communicate a coherent security strategy do not paint an optimistic picture for the remaining five years of López Obrador’s term. So far, he has been able to blame his predecessors for inherited problems, but at some point voters won’t accept that anymore.

“How to marry this ‘humanist’ and ‘progressive’ vision of the president and his government with the undeniable reality and undeniable necessity of containing not just the drug trafficking groups but also the ordinary criminal violence” is the question faced by Mexico’s president, according to Erubiel Tirado, coordinator of the national security, democracy and human rights program at the Iberoamerican University in Mexico City.

The most visible element of a security strategy under López Obrador, though not a strategy in itself, was the creation of the National Guard. The new fighting force was supposed to fill the security void created by corrupt, disbanded or outmatched police forces around the country and to an extent lessen the country’s dependence on the use of the military for domestic policing.

A large portion of the guard, however, was immediately detoured to immigration enforcement duties under pressure from the United States.

“They’re not a police force that is professionalized, that is trained in conducting investigations, surveillance, intelligence and that have special teams to conduct arrest operations in a finer way, not through confrontations in the streets,” said Tony Payan, director of the Center for the United States and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston.

It also remains unclear how the National Guard fits with the social programs that López Obrador said will attack the root causes of crime in Mexico.

“There doesn’t seem to be any kind of holistic or integrated thinking about how you link violence-prevention programs, which the government talks a lot about, with actually prosecuting organized crime,” said Duncan Wood, director of the Wilson Center’s Mexico Institute.

López Obrador also said little about strengthening Mexico’s justice system, which is a key component of reining in the country’s security problems.

The lack of a clear strategy worries not only Mexicans, but their neighbors to the north.

In October, Payan visited with personnel at the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City who expressed concern.

“They clearly said that they were waiting for the (López Obrador) administration to have a clear strategy and to communicate to them what the administration intends to do and how they intend to do it,” Payan said.

The U.S. has enjoyed varying levels of cooperation from recent Mexican administrations in prosecuting the drug war, but has been struggling to find the channels for that cooperation under López Obrador.

“The sense that I have from my conversations is that the López Obrador administration considers these American agencies as part of a war on drugs that he wants to put behind him,” Payan said.

In the case of Ovidio Guzmán, the U.S. has requested his arrest for extradition.

On Thursday, López Obrador, responding to speculation the U.S. government had pressured Mexico to act, said flatly: “We do not take orders from Washington.”

Wood, of the Wilson Center, doubted this would be the last time we see Mexico go after a drug lord under López Obrador, because the U.S. pressure is not going to go away.

“There was huge disappointment on the part of folks in Congress and in the State Department and intelligence services with the way that the Culiacan mission was mishandled,” Wood said.

“Now, the question is, next time that they capture a high-value target, what will they do if faced with the same kind of situation? Will they back down or will they double down?” Wood asked. /kga