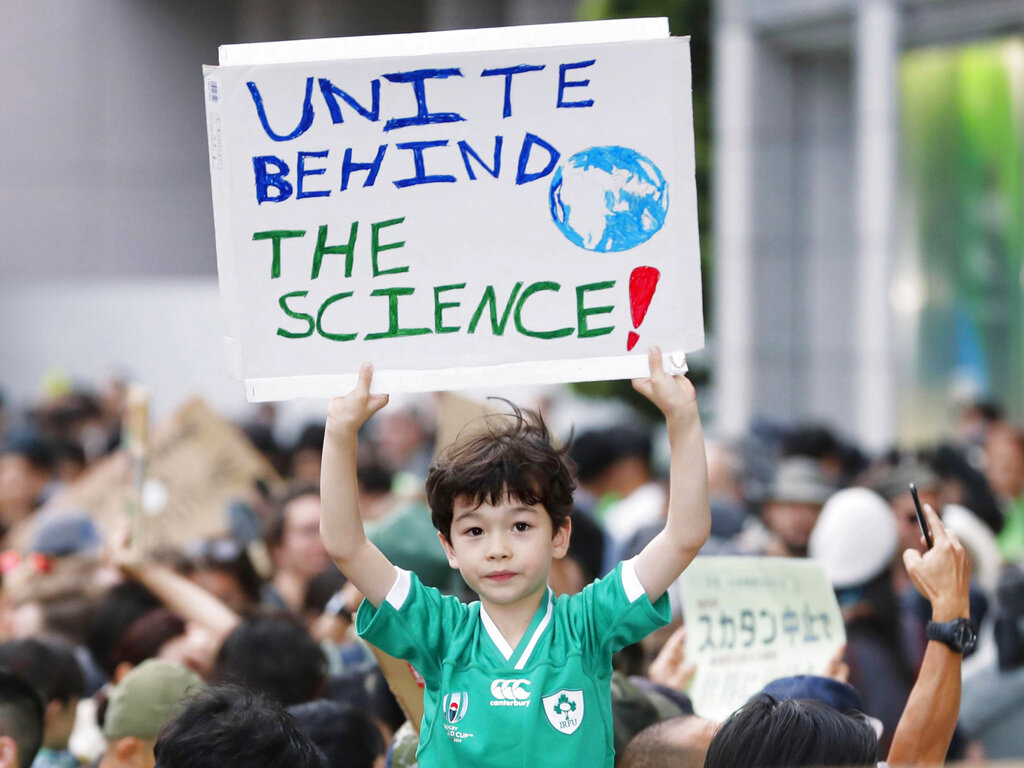

In this Friday, Sept. 20, 2019, photo, a boy holds up a placard while joining a rally, calling for action to guard against climate change in Tokyo. Young people afraid for their futures protested around the globe Friday to implore leaders to tackle climate change, turning out by the hundreds of thousands to insist that the warming world can’t wait any longer. (Kyodo News via AP)

SINGAPORE — One of the most devastating impacts of climate change in Asia is set to be rapid melting of glaciers in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, the source of 10 major rivers.

Temperatures are already rising faster in this vast mountainous zone than the global average, speeding up melting of glaciers that provide water for farmers, hydro-electric power plants and drinking water for millions of people.

Major rivers including the Brahmaputra, Ganges, Indus and Mekong are also critical for regional economies and demand for water is growing as populations increase.

The Hindu Kush Himalayan region covers all the high mountain chains of Central, South and Inner Asia and comprises thousands of glaciers, stretching from Afghanistan to Myanmar and including the Tibetan Plateau.

“This vast complex of high mountains produces one of the world’s largest renewable supplies of freshwater. The Himalayan region has the largest reserves of water in the form of ice and snow outside the Polar Regions and that’s why it is called the ‘third pole’,” said Dr Anjal Prakash, Associate Professor, Regional Water Studies, at TERI School of Advanced Studies in India.

About 250 million people live in this region and a further 1.65 billion people rely on its river flows downstream.

The danger is that rapid melting will, initially, increase water flows in the next few decades. Meltwater feeding the rivers would then decline as the glaciers shrink.

That could trigger unrest as nations clash over water supplies.

Underscoring the risks, a study by Himalayan Adaptation, Water and Resilience Research (HI-AWARE), a regional scientific collaboration, calculated that the water consumption in downstream areas of the Indus, Ganges, and Brahmaputra basins is projected to increase by 24 percent, 42 percent and 107 percent, respectively, during this century.

Water use for industrial and domestic purposes is projected to increase three to sevenfold.

Over-extraction of ground water has already led to water shortages in some areas, which could become worse during droughts that climate scientists predict will become more intense and last longer.

Dr Prakash said that even with the most ambitious goal of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5 deg C by the end of the century, temperatures in the Hindu Kush Himalayan would rise 2.1 deg C and one-third of the region’s glaciers would melt.

If global climate efforts fail, current emissions would lead to warming of up to 5 deg C warming and the loss of two-thirds of the region’s glaciers by 2100.

Worse, climate computer models also project higher rainfall in the region if temperatures rise sharply.

This would lead to significant losses in glacier volume, from 36 per cent to 64 per cent, depending on the warming scenario, Dr Prakash, a coordinating lead author of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report on oceans and ice-covered parts of the globe, told The Straits Times.

The report is due for release on Sept 25.

With a certain amount of global warming locked in because of the greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere, nations reliant on Hindu Kush Himalayan waters may have to adapt, Dr Prakash said.

But also urgent is increased coordination and management of the region’s water resources, which he said is lacking because of distrust between governments.

“This precedes the ineffective and inefficient management of water at virtually all levels in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region. There are eight countries that share the Hindu Kush Himalayan boundary but in most of the countries, water management is inward-looking with little attention paid to long-term cooperation for better water management,” he said.

“The river systems are the economic engines of the region, especially due to the large freshwater reserve, biodiversity and natural resource support that it provides for the billions of people living downstream.”

What happens to them will directly affect more than half Asia’s population, he said.