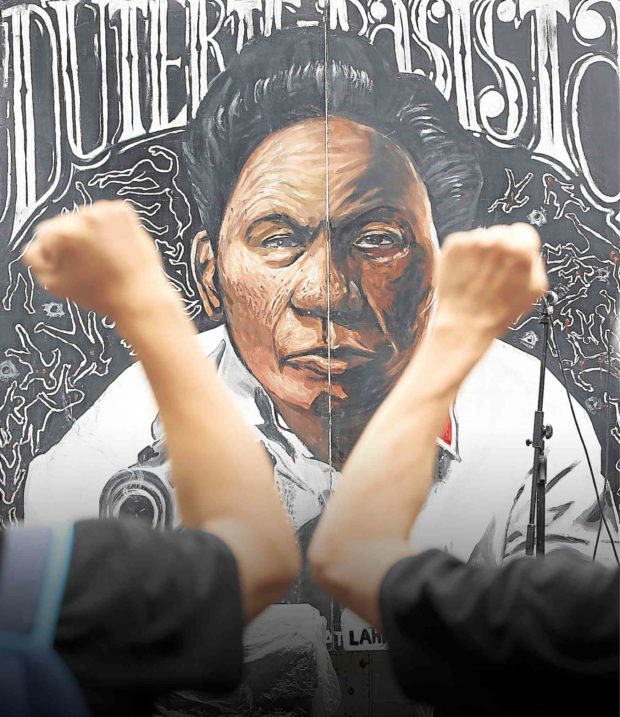

NEVER TIRE, NEVER AGAIN Militant groups gather at Mendiola in Manila for a rally on Friday marking the 47th anniversary of the declaration of martial law during the Marcos regime. —MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

MANILA, Philippines — When this teacher discusses history in the classroom, she doesn’t require her Grade 7 students at the Philippine Science High School (PSHS) main campus to recite specific dates and events by rote.

Instead, Cristina Cristobal, 61, leads her students in analyzing historical artifacts and documents that would help them develop a deeper understanding of certain events that they did not personally witness.

Her students “get to interact with remnants [of the past],” Cristobal tells the Inquirer. “They don’t just read it from the textbooks, which are very dry and very detached from their own experience. What’s important is they get to connect with the past even if it happened a long time ago.”

For her use of primary sources in teaching history, Cristobal received on Sept. 4 the Metrobank Foundation Outstanding Filipino Award for Teachers, a career-service award for exemplary Filipino professionals in the academe.

Her legacy as Quezon City’s Veteran Innovator in History Instruction can be best captured by her initiative to inspire changes in the students’ perspective toward learning history.

Mind-changer

In studying the martial law era—considered one of the darkest moments in contemporary Philippine history—Cristobal’s students are guided through a visual analysis of the amendments in the 1935 and 1973 constitutions, along with the 1976 amendments, presided over by the dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

Proclamation No. 1081 imposing martial law on Sept. 21, 1972, and the creation of the 1973 Constitution signaled the collapse of the government’s system of checks and balances, with the President gaining full legislative powers as well as the sole authority to appoint members of the Supreme Court.

To illustrate this, Cristobal, who has been teaching at PSHS for 39 years, first draws a graphic organizer: a big circle that symbolizes the President’s executive powers, and two more circles representing the other branches of government within it.

This step encourages students to identify the changes made in and the differences among the constitutions.

“Even the students who once thought martial law was a good chapter in history changed their minds,” she says.

To make her students fully understand the gravity of the atrocities committed during martial law, Cristobal provides them statistics on human rights violations.

Historical distortion

But the most poignant primary source is neither a document nor an artifact from the era. “We had one of my former coteachers who was imprisoned, tortured and raped during martial law as speaker in our humanities festival last year,” Cristobal recalls. “The students were able to interview her and ask questions about her experiences while she was in jail.”

And the students, of varying backgrounds and exposures to views on martial law, were horrified: “They couldn’t believe that such things actually happened.”

Critics have condemned attempts at “historical revisionism” by the late dictator’s family members and their associates. But Cristobal contests the term, pointing out that it is through historical research and findings, that knowledge of and information about the past are updated and “revised.”

She would rather call it “historical distortion.”

“When you change the facts to suit your personal agenda, that’s historical distortion, and that is never good,” she says.

MYTH-BUSTING MA’AM History teacher Cristina Cristobal of Philippine Science High School has found a way for her students to have a deeper, unvarnished understanding of the Marcos regime. She is a big help to those who are commemorating the 47th anniversary of the declaration of martial law with a rally in Manila on Friday and may still change the mind of a 29-year-old man who had an image of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos tattooed on his hip at the Dutdutan skin art festival in Pasay City. —MARIANNE BERMUDEZ

In 2014, the second year of the implementation of the K-12 program, the Department of Education (DepEd) ordered the removal of Philippine history from the Grade 7 curriculum in favor of Asian history.

The varying accounts and versions of “truth” encouraged Cristobal to push for the retention of Philippine history in the curricula of regular secondary schools in the country.

Cristobal says the Metrobank Foundation gave the awardees a choice in discussing their innovations and legacy: to conduct a lecture on their chosen topic or to present their future plans in a roundtable with government officials. She says she chose the latter.

Deepening the discussion

“We are lucky in PSHS that we are able to create our own curriculum,” she says. “The DepEd strengthened Philippine history in Grades 5 and 6, but the problem is that the students’ learning is halted once they enter high school. They are going to encounter Philippine history again in college, but they would have a different maturity level by then. We need to further deepen the discussion.”

Cristobal, who first took up education and majored in foreign studies at the University of the Philippines (UP), recalls that it was only during her first semester that she developed a deeper understanding of Philippine history.

“I realized that I didn’t really learn much about Philippine history when I was in grade school or high school,” she says. “I asked myself, ‘Why am I only learning this now?’ Then I shifted to history in the second semester. I knew that students needed to learn about this, too.”

It was through her Ph.D. dissertation at UP, which focused on the historical thinking skills of selected high school students, that Cristobal thought of introducing a different teaching method.

In her study, she considered two possible factors that could influence a student’s thinking skills: socioeconomic status and age. But she discovered that neither had a significant effect on their ability to analyze history.

“A student, whether rich or poor, young or old, can look at a source document critically. It is their education that really matters: The training that they get from schools is a major factor in developing critical thinking,” she says.

Poor education

Cristobal laments how poor education made it possible for voters to elect political figures with corrupt backgrounds to high government positions.

“We cannot simply forgive and forget,” she warns. “They have to be held accountable … Because of the weak instruction of history in the country and therefore the poor assertion of our rights, the Filipino people still elect them. It really has something to do with the education the people got.”

And it is through her teaching method that she prevents her students from becoming victims of historical distortion, especially in discussing martial law.

“It is important that they know the truth about martial law so they can be conscious in fighting for and protecting the rights that we enjoy today,” Cristobal says.