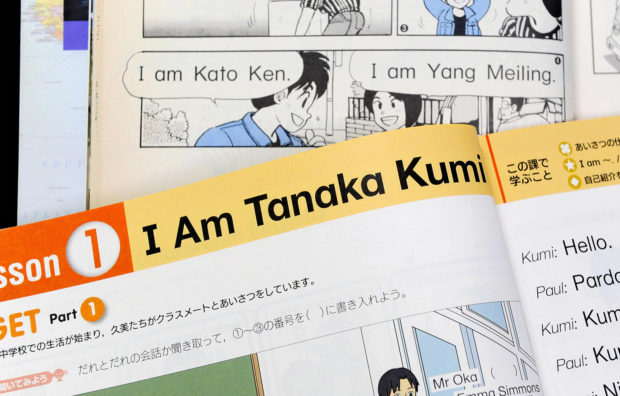

Sanseido Co. adopted the surname-first order for its “New Crown” textbooks before the Cultural Affairs Agency issued its notification. (1993 edition above, 2016 edition below). The Japan News/Asia News Network

TOKYO — The Japanese government is coordinating over issuing recommendations to use the “surname-first” order when names are written in Roman letters.

The idea was proposed by Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology Minister Masahiko Shibayama and Foreign Minister Taro Kono at a press conference on May 21.

Shibayama said the Cultural Affairs Agency would issue a notice to administrative and educational bodies and the media recommending use of the surname-first order.

Kono also said he intended to ask major international news organizations to use this order.

The ministers have in mind a report submitted in December 2000 by the then Council on National Language, an advisory panel to the education minister.

The report stated that “the diversity of human language and culture should be recognized and put to use by the entire human race,” concluding that “it would be desirable to adopt the surname-first order.”

That month, the agency issued a notice to administrative and educational bodies and the media organizations, asking them to act accordingly.

Kono said at the May press conference that the recommendations are being issued again because of “the new Reiwa era and with the Tokyo Olympics coming.”

The agency has since surveyed the Cabinet Office, ministries and agencies, finding that most foreign language websites, administrative documents and others would be able to use the surname-first order.

On the other hand, at some ministries and agencies, laws and regulations require that documents use the given-name-first order. Changing this would require regulations to be revised or systems to be modified.

Legacy of Westernization

The order of given name first began to permeate society as a result of the Westernization policies of the mid-Meiji era (1868-1912) and took root through English education, according to Haruo Erikawa, a professor at Wakayama University and chairman of the Society for Historical Studies of English Learning and Teaching in Japan.

He said that around the year 1900, English textbooks adopted the given-name-first order, which then became mainstream.

After the Cultural Affairs Agency issued its notice in 2000, all English textbooks used at junior high schools adopted the surname-first order, but the practice did not take root.

“The Cultural Affairs Agency notice has not permeated because of a long cultural history of ‘admiration of the West,’” Erikawa said.

He added, “It’s up to the individual how to give their name. However, name notation is one way of exercising sovereignty. Politicians and people involved in diplomacy should use the surname-first order.”