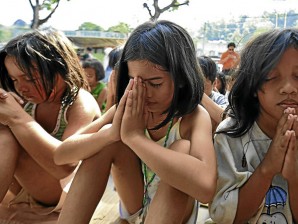

SILENT WISH Children pray at an evacuation center in Cagayan de Oro City during a healing session aimed at helping them come to grips with the devastation caused by Tropical Storm “Sendong.” AFP

ILIGAN CITY—Flanked by the sea to the west and the river to the east, the settlers of Bayug Island knew that it was only a matter of time before the waters around them reclaimed the land.

Talk of “tsunami” went the rounds after the great one rose from the Indian Ocean in 2004, and anxious residents kept watch over the waves of Iligan Bay. Some tied boats to coconut trees as a precautionary means of escape from the fury of the sea.

They never expected that the deluge would come from behind—the Mandulog River—and that the waves whipped up by Tropical Storm “Sendong” would leap from inland toward the sea rather than the other way around.

“It was a backward tsunami,” resident Erlito Echavez told the Inquirer on Wednesday morning, shaking his head.

“We were worried about the sea in front of us. We never thought we would worry about the river behind us,” said the 52-year-old fisherman.

But the lessons of Sendong are hard to heed.

As scores of victims lay huddled in evacuation centers across this coastal city, some swearing never to return to Bayug, a few had started rebuilding their homes.

Island no more

Sendong wiped out nearly all the settlements on Bayug, stripped the topsoil, uprooted trees, toppled houses, and obstructed the narrow channel that had broken off from Mandulog and that used to separate the island from the rest of Iligan.

As a result, Bayug has been “reconnected” to the Mindanao mainland, according to David Almarez, a professor of Mindanao State University-Iligan Institute of Technology (MSU-IIT).

“Bayug is no longer an island,” Almarez said.

Per Almarez’s estimation, it will take only 50 years for the entire land mass to be devoured by the two bodies of water surrounding it.

He said that in the past 20 years, the soil had been steadily eroding and the water creeping up the coastline as the land lost more and more ground not only to the river but also to the sea.

Almarez, manager of the Bayug Mangrove Rehabilitation and Reforestation Project led by MSU-IIT, said Bayug was originally just silt that formed into a land mass thousands of years ago, making the island habitable for the first settlers.

“This is a danger zone,” he said. There were some 400 houses on Bayug before Sendong, he said, and the Inquirer counted only a little more than 20 that remained standing, with varying degrees of damage.

Echavez said he himself was not thinking of leaving because he believed that his family could make it through another onslaught of Sendong’s magnitude.

At the height of the storm on Friday night, the fisherman herded his wife, six children, a visitor and two dogs onto a large pump boat he had secured with rope to a tree near their house.

There they hung on for dear life as the waters swelled and surged around them.

Hardened mud

It was quiet early on Wednesday when the Philippine Daily Inquirer visited Bayug, now more accessible and easier to negotiate with the mud hardening under the hot sun for the past few days.

Weeds, bushes and fallen trees were flattened against the mud, appearing, eerily, to point in one direction—to the west, toward the sea.

Echavez and his family were hard at work cleaning their muddy house even as the stench of corpses, many of them his own neighbors, filled the air.

More than a thousand have been reported dead in Iligan and neighboring cities, including Cagayan de Oro, and hundreds more remain missing.

Except for the houses of the Echavezes and a handful of other families, Bayug has become a no man’s land.

Evidence of Sendong’s destruction was everywhere—from the remains of houses and furniture littering the landscape, logs and timber scattered on the beach, to the dead animals and three newly discovered bodies releasing putrid smells.

There was neither electricity nor running water. The residents cleaned themselves and their muddied homes using water from deep holes they had dug in the ground and cooked food by wood fires.

Echavez’s wife Winifreda, 50, expressed worry that another storm would come to complete what Sendong had started.

“[But] we have nowhere to go. This is our life,” she said.

Irony

Almarez said he found it ironic that Bayug was nearly wiped out, not by the sea, but by the swollen river abetted by rain from the uplands.

He said he and his colleagues at MSU-IIT had been working to restore and rehabilitate the mangrove forests that used to line the coast facing the sea like a protective mantle.

Since February, he and volunteers from the university have planted 20,000 mangrove “propagules,” which only recently began to shoot leaves.

As he inspected the devastated shoreline, Almarez saw that all their efforts had been laid to waste, with only the bamboo sticks that were used to support the mangroves now jutting from the still water.

“We will have to reassess our next move, if it is still workable to replant,” he said.

Almarez said the disaster, the worst to hit this southern heartland in decades, was the result of a number of factors, mostly lack of foresight and little concern for the environment.

“Everybody is to blame, from the residents who burned the mangroves for firewood to the cement companies that used them for fuel, other companies that quarry and the illegal loggers,” he said.

The logs that smashed into countless homes, scattering and killing people, traveled several kilometers from upland towns, he noted.

Almarez, whose day job is as head of the school’s human resource management division but goes weekly to Bayug to oversee the rehabilitation of the mangroves, expressed hope that the tragedy would galvanize support for the project, an extension effort of MSU-IIT.

“The experience of Bangladesh and India during the 2004 tsunami showed how mangrove forests were effective as barrier against onrushing waters,” he said.

Child’s dream

On this visit to Bayug, the Inquirer spotted children playing in the ruins of their houses, with no adult supervision.

Many children died on the island, and many others were orphaned, residents said.

In the middle of the conversation with the Inquirer, Winifreda Echavez saw a bright girl with a bounce in her step and called the child to her side. The mere sight of 7-year-old Michaela Tabilon brought tears to her and her husband’s eyes.

Speaking in Cebuano, the first-grader started to talk about a “dream” she had on Tuesday night. She said she was about to doze off when she felt her mother, Riza, take her usual place in bed and hug her.

She said she woke abruptly and stayed awake, crying, for the rest of the night because “it was just a dream.”

The child’s parents, Riza and Michael Tabilon, and her brothers Mikee Angel, 3, and Mico, 5, perished in the great flood that wrecked their home. She clung to a banana tree as her family members were washed away.

Tabilon broke off from her story and began to cry. There was no dry eye from the small rapt crowd around her.

She visited what remained of her house and cried again. An aunt now takes care of her, neighbors said.

Similar stories of tragedy abound in Bayug, according to Almarez.

But likely as not, he said, the villagers would repopulate Bayug, which could vanish from the face of the earth in a matter of decades.

“Filipinos are a stubborn people. They will be back on Bayug,” he said.