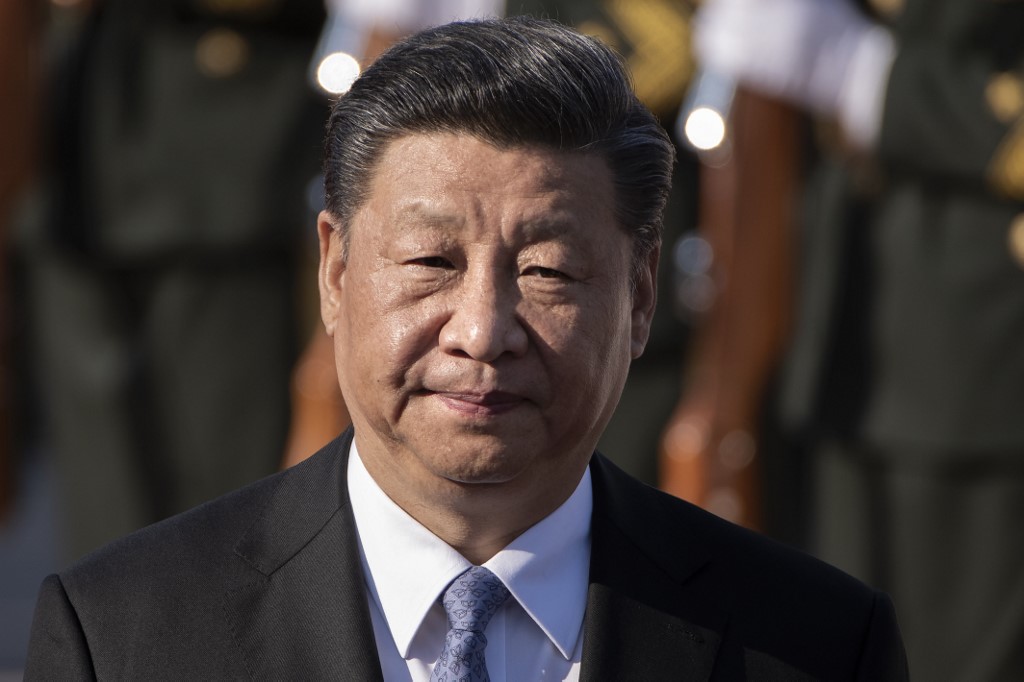

Chinese president Xi Jinping walks during a welcome ceremony for Bulgaria’s President Rumen Radev at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on July 3, 2019. (Photo by NICOLAS ASFOURI / AFP)

But as the People’s Republic of China approaches its 70th anniversary on October 1st, Xi finds himself battling threats on multiple fronts.

From a biting US trade war to relentless protests in Hong Kong challenging his rule and international condemnation over Beijing’s treatment of Uighur minorities in Xinjiang, Xi is having a very bad year, analysts say.

Furthermore, the crises have left him with limited room to act and simultaneously shore up support at home.

“Xi Jinping has had the toughest year since he came to power”, said Eleanor Olcott, China policy analyst at research firm TS Lombard.

“Not only is he facing unrest on China’s peripheries in Hong Kong and Xinjiang but the trade war is weighing on an already slowing domestic economy.”

Few expected things to turn out this way.

In Davos in 2017, just weeks after the inauguration of protectionist Donald Trump as US president, Xi was at pains to portray himself as a champion of globalisation, outlining a role for China as a world leader.

Some even hoped he would open the door to further reform. But those expectations have now sunk.

“The Xi Jinping of Davos 2017, who emerged on the world stage as defender of the liberal global economic order, is unrecognisable today,” said Olcott.

By the time he secured his second term as the Communist Party’s general secretary in October 2017, Xi was at the centre of a cult of personality built by the state.

Last year, he enshrined “Xi Jinping Thought” in China’s constitution and, in a shock move, removed term limits on individuals — overturning an orderly system of succession put in place to prevent the return of another all-powerful strongman like Mao Zedong.

Xi has used crackdowns on corruption and calls for a revitalised party to become the most powerful Chinese leader in decades, and the constitutional changes mean he can rule for as long as he wishes.

‘Major challenges’

But stamping his personal brand on the government means Xi’s leadership is directly intertwined with the current headwinds.

An unexpected and festering trade war with the United States has eroded confidence and hit the economy hard.

Furthermore, his signature Belt and Road (BRI) global infrastructure initiative has faced setbacks, with critics saying the plan is designed to boost Beijing’s influence, lacks transparency and will saddle partner governments with debt.

The crackdown on Uighurs in Xinjiang — a region deemed crucial to the BRI’s success — has come under heavy international condemnation for reportedly placing an estimated one million mostly Muslim ethnic minorities in internment camps in the name of counterterrorism.

“Xi largely created the problems that are now major challenges for him and for China,” said Steve Tsang, a China-Taiwan relations expert at the School of Oriental and African Studies.

“They are all products of Xi’s policies.”

But the biggest challenge to Xi’s authority has come from the semi-autonomous hub of Hong Kong and it appears to have caught him off-guard.

Dramatic images of mostly young pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong facing riot police amid clouds of tear gas have dominated global newspapers and websites for weeks, as a movement calling for universal suffrage gathers pace.

Hong Kong, which was handed back by Britain to China in 1997, is ruled under a “one country, two systems” policy which gives citizens liberties unseen on the mainland.

Protesters say those rights have been steadily eroded and have openly criticised an increasingly assertive Beijing — provoking fears China will resort to a heavy-handed intervention to quash the unrest, unleashing disastrous consequences.

Still in charge

Despite the hurdles facing him, however, the embattled leader’s hold on China remains firm — for now.

“None of the challenges has ‘blown up’ sufficiently for anyone within the top leadership to openly challenge him. As long as they stay in the shadow, Xi remains in charge,” said Tsang.

And while international criticism mounts, analysts say Xi and the Communist Party can potentially exploit the attacks on him to serve Beijing’s broader ideological needs.

“The CCP media machine has successfully framed the trade war and Hong Kong protests as a result of unfair foreign intervention that seeks to perturb China’s rise,” said Olcott.

“Xi will play up this narrative at the 70th anniversary celebrations, and stress that China must forge its own development path according to the Chairman’s guiding ideology.”