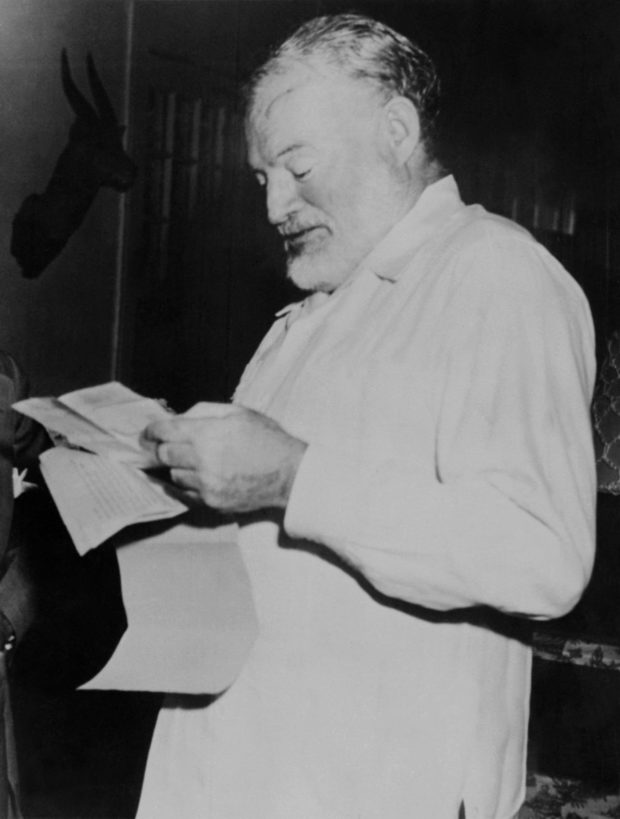

The day Hemingway ‘liberated’ the Ritz bar in Paris

PARIS — Even for Ernest Hemingway, a man whose bravado was matched only by his thirst, his liberation of the Ritz Hotel’s bar in Paris was the stuff of legend.

Officially the Nobel prize-winning author of “A Farewell to Arms” and “The Sun Also Rises” was supposed to be a war correspondent for the American magazine Collier’s when he entered the French capital on Aug. 25, 1944.

In reality, the macho novelist, who strode from a commandeered Jeep with all the swagger of a general to take over the city’s most luxurious hotel, was waging his own swashbuckling private war against the Third Reich.

Having survived World War I and the Spanish Civil War — where he similarly blurred the lines between reporter and combatant — Hemingway managed to get himself embedded with the US 4th Division troops that landed on the Normandy beaches on D-Day.

Like some other “glorious amateurs” who had volunteered to help the Office of Strategic Services, a branch of the US intelligence services, he spent a month hurtling in a Jeep between the front lines, making contact with local French Resistance fighters between the advancing US forces and the retreating Germans.

‘First American in Paris’

It was exactly the sort of high-risk, self-dramatizing situation that the writer reveled in, even if it embarrassed his estranged wife Martha Gellhorn, who took her job as a war reporter far more seriously.

One of those Resistance fighters later remembered Hemingway’s obsession with the luxury Paris hotel, saying he talked of little else but “being the first American in Paris and liberating the Ritz.”

Hemingway became enamored with the Ritz as a penniless writer in Paris in the 1920s along with F. Scott Fitzgerald, a time he later immortalized in “A Moveable Feast.”

With the help of his contacts in the American armored division, commanded by the equally flamboyant Gen. George S. Patton, Hemingway wrangled a meeting with French commander Gen. Philippe Leclerc, whose tanks had been given the honor of liberating Paris.

His humble request: to be given enough men to liberate the Ritz’s bar.

To the writer’s surprise, he got a frosty reception and was dismissed. But Hemingway persevered and on Aug. 25 he turned up at the hotel on Paris’ beautiful Place Vendome in a Jeep mounted with a machine gun at the head of a group of Resistance fighters.

He burst into the hotel and announced that he had come to personally liberate it and its bar, which had served as a watering hole for a long line of Nazi dignitaries, including Hermann Goering and Joseph Goebbels.

51 dry martinis

The manager of the hotel, Claude Auzello, approached him and Hemingway demanded: “Where are the Germans? I have come to liberate the Ritz.”

“Monsieur,” the manager replied, “They left a long time ago. And I cannot let you enter with a weapon.”

Hemingway put the gun in the Jeep and came back to the bar, where he is said to have run up a tab for 51 dry martinis.

“He wore the uniform and gave orders with such authority that many thought he was a general,” the Ritz’s head barman, Colin Field, recalled.

According to Hemingway’s brother Leicester, the writer searched the cellar with his men, taking two prisoners and finding an excellent stock of brandy.

Inspecting the roof and the upper floors, they found nothing but sheets drying in the wind, which they riddled with bullets just in case there were Germans lurking behind them.

Hemingway later wrote that he could not stand the thought that the Germans had soiled the room he shared with his lover Mary Welsh, whom he would marry in 1946. The two remained together until his suicide in 1961.

Hemingway wrote of his stay in the hotel with his group of irregulars in a 1956 short story, “A Room on the Garden Side.”

His high jinks at the Ritz did not escape the attention of his superiors, with some pushing for him to be court-martialed for carrying arms as a war correspondent.

The charges were quietly dropped, however, to avoid embarrassment to the US intelligence services, and after the war the writer was quietly awarded a Bronze Star Medal for working “under fire in combat areas to obtain an accurate picture of conditions.”

Even the Ritz eventually forgave him, naming a small bar after Hemingway in 1994.